Why it’s too soon to cheer that households are borrowing less

Once you’re talking about a $1.7-trillion mountain of household debt, even a small rate of increase is going to be jaw-dropping

Ill piggy bank with bandages

Share

When the latest figures related to household debt were released last Friday, showing a microscopic decline in the debt-to-disposable income ratio from 164.2 per cent to 164, a common theme took hold: Canadian households have learned the lesson that too much debt is dangerous.

Never mind that Statistics Canada had revised up the third-quarter figure from an original estimate of 163.7 per cent, meaning the celebrated decline of 20 basis points is less than half that estimate error. The lower figure was fodder for those who’ve been saying debt levels are less of a concern because the growth of debt—the pace at which Canadians are piling it on—is slowing.

You’ll have heard this argument a lot. Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz has said it. So has outgoing RBC CEO Gord Nixon. Former Finance Minister Jim Flaherty liked to bring it up from time to time, and it’s a safe bet his successor, Joe Oliver, will too.

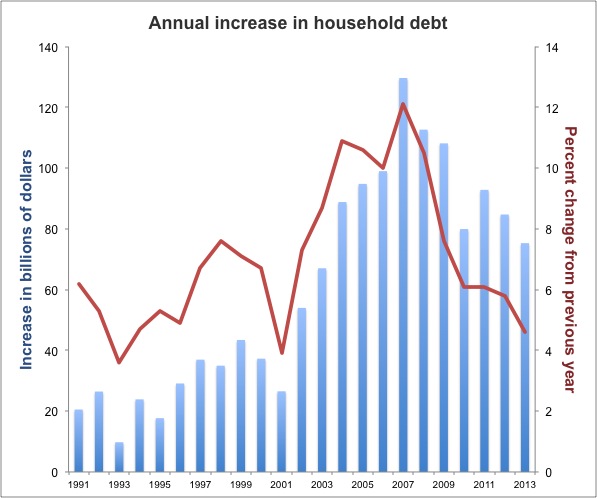

Here’s why the slowdown isn’t something to get excited about. Even though the rate of household debt growth has slowed to levels seen only twice in the past quarter-century, in absolute terms the amount Canadian households are piling on remains staggering.

As of December, households had added $75 billion in additional credit, including mortgages, consumer credit and other non-mortgage loans, compared to the year before—a figure nearly three times greater than the debt households added in 2001. (Data are from Statistics Canada CANSIM here.) Obviously your paycheque hasn’t hasn’t tripled since then, though the value of your house may have, and for a lot of people that alone is enough to wash away any worries.

Once you’re talking about a $1.7-trillion mountain of household debt in Canada, even an increase of a few per cent each year is going to result in a jaw-dropping additional burden.

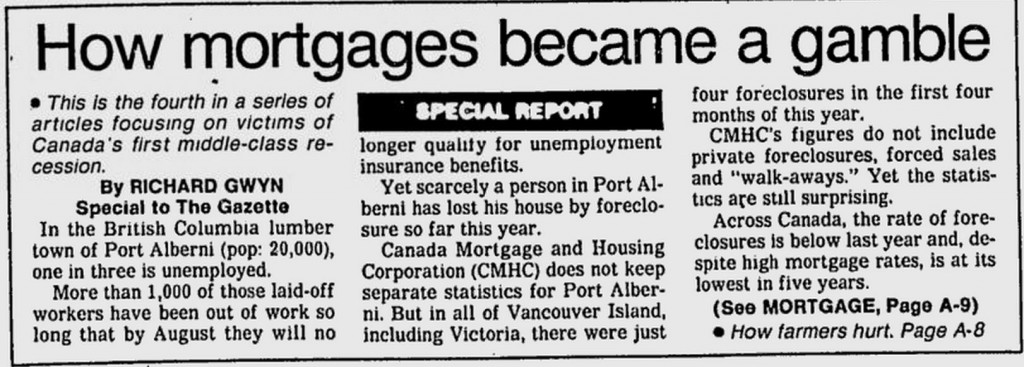

One last thing. Because I actually just heard someone say “Condos are an easy way to make a quick buck so you can afford the downpayment on a house” I thought it a good time to share a newspaper clipping I came across while sifting through the Google newspaper archive. Any time you get to thinking there’s something new under the sun, a classic story like this one from the fantastic Richard Gwyn on June 9, 1982 is recommended reading:

In the mid-‘70s Canadians stopped buying houses. We started buying investments, because we all figured out that house prices would rise faster than inflation, and, best of all, that any profit was exempt from capital gains tax.

We contentedly bought over-priced houses because we knew we could later unload them for even more. Between 1970 and 1979, the price of an average house, and so the value of the owner’s equity, almost tripled, from $23,000 to $62,000. Then, in 1980 and 1981, until the fall, prices really took off.

Not all Canadians understood what was going on. Many did. In 1980-81, average monthly mortgage payments in Vancouver doubled. Yet there were few complaints.

The reason was that average house prices jumped by $100,000 in a 12-month period, netting their owners a windfall often equal to three, and even four times, their annual salary.

…

High-interest rates have changed the rules in mid-game. Typically, in Vancouver, one couple bought a second house for $300,000. They put their first house up for sale just as the bubble burst. Both houses are now on the market, listed at half their purchase price; no matter what happens now, the couple will be in debt for the rest of their lives.

Despite claims by the Toronto Real Estate Board that “average” prices are little changed from a year ago, the reality is that houses above $150,000 are almost unsaleable, and when sold the vendors often have to offer mortgages two or three percentage points below the going rate. Recently, during a half-hour bicycle spin in the affluent Toronto suburb of Rosedale, a housewife counted 82 For Sales signs.

From: