Aurora College has produced a chilling map of violence against women in the N.W.T.

Now that Pertice Moffitt knows where it happens, the next question is how to help.

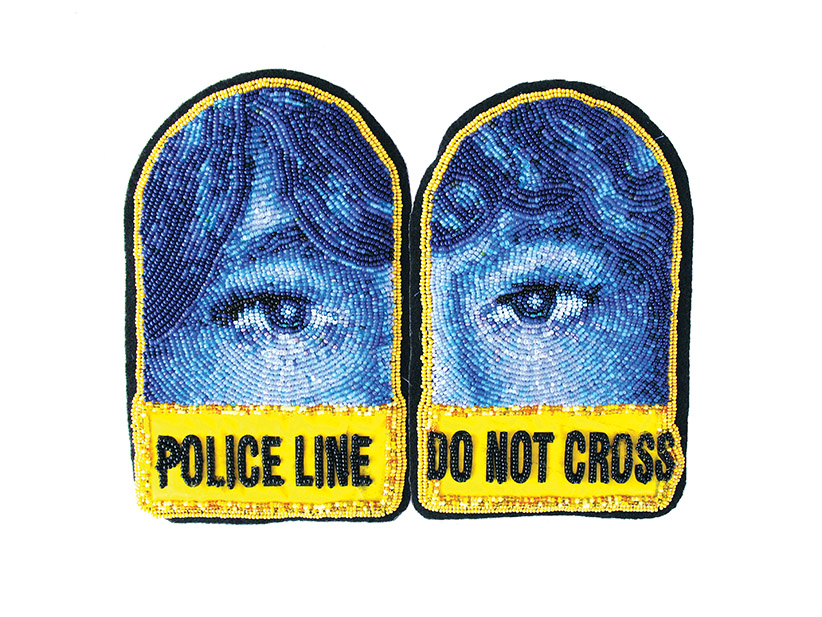

Moccasin vamps (tops). (Teresa Burrows/Walk With Our Sisters)

Share

Hers is not an angry or brittle voice: She speaks softly and sounds filled with determination and hope. Yet Pertice Moffitt has just spent five years studying intimate partner violence in the Northwest Territories, a desolate epidemic that she has documented in every single community.

Working with University of Regina geographers Paul Hackett and Joe Piwowar, as well as social workers, students and community organizations, the manager of health research projects at Aurora College’s North Slave Research Centre has produced a chilling map that shows where violence against women happens most in the Northwest Territories, which, she is careful to point out, is just a first step to in trying to understand its causes and redressing it.

After charting the occurrences, Moffitt consulted with front-line workers such as the RCMP, nurses, community-health workers, and leaders in victims’ services and women’s shelters to construct what she calls “an evolving theory” of the cycle of abuse.

Intimate partner violence is a woeful constant in the N.W.T. Aurora College president Jane Arychuk recalls that, in the 23 years she spent living and working as an educator and principal in one community, it was not uncommon to see women with black eyes, injuries they did not talk about or hide, but rather displayed with a measure of defiance.

Cheryl Cleary, an ambulatory-care social worker at Stanton Territorial Hospital in Yellowknife, cries when she remembers how “normalized” violence against women was when she grew up in the Great Bear Lake region. She notes that abusers have changed their strategies so as to hide the marks they make on their victims’ bodies, and says the victims’ shame and isolation lends to an atmosphere of silence and taboo regarding the problem.

Cleary worked with Moffitt on the study, which triggered a lot of memories for her, and encouraged her, as well. She hopes it will be “a starting point to get the information out there without stigma, and toward dialogue and discussion.”

The existence of intimate partner violence has roots in generations of violence; it often comes in tandem with alcohol abuse, with the rigours of poverty and, most of all, with a lack of access to mediation, care, shelter and protection. In many regions, there is nowhere to go. Only five of 33 communities have a shelter, and two of those are not open consistently; 11 communities have no RCMP. Many homes have no phone, and there is no cellphone reception. “What can a woman do?” Moffitt asks, her voice, just once, ringing with despair.

In order to answer the question, Moffitt and her colleagues have brought their work to various NGOs, government representatives and “concerned individuals,” and to Aurora College itself, giving talks in order to “bring more education and awareness” to the issue.

The work with the community is ongoing. A non-Aborignal woman, Pertice has earned the trust and confidence of the region’s women, so much so that she was named one of the N.W.T.’s Wise Women of the Year in 2015. She brings this wisdom to her one-on-one work with the victims of intimate partner violence, and to her research. When the Walking with Our Sisters exhibit came to Yellowknife (each beaded-moccasin upper representing one of the more than 1,200 murdered or missing Aboriginal women), she was at the centre of the discourse about the massive crisis facing Indigenous women. Some of the women counted among the victims of intimate partner violence for the map have been murdered.

She has scheduled meetings with the RCMP and sought other decision-makers so she can share the findings of the study and, Moffit asserts, develop “a plan of action” that addresses gaps in services and viable means of sustaining non-violent communities.

What does Moffitt envision? Noting the phenomenal strength and resistance of Aboriginal women, she sees them in a “strength-based place” where they “develop resilience and coping mechanisms,” and where there are front-line workers at hand to keep them safe. She also sees help for the perpetrators, through education and awareness.

A Native elder spoke to her about education, which he compared to a leaf in water that you gently place your hand on, without driving it under.

“There was gentleness and respect, once,” she says, citing the elder. And as she continues to set up ways to shatter the silence, shame and fear, and as she rallies the troops and stays on message—that everyone should be treated with parity—Moffitt continues to build hope for genuine solutions to the problem that she has named, pinpointed, studied and begun, astonishingly, to solve.

[widgets_on_pages id=”Education”]