Are universities doing enough to support mental health?

Students report feeling overwhelmed while their schools struggle to address the demand for help

Student in library. (Sutichak/Shutterstock)

Share

University isn’t meant to be easy, but it isn’t supposed to be this hard: since November 2016, the University of Guelph has lost four students to suicide.

After the fourth death, in mid-January, the school sent out another statement reminding staff and students about the counselling services available to them. For recent grad Connie Ly, it wasn’t enough. “I really just questioned how useful the services were, given that they were so overwhelmed already,” she says. Ly launched a petition on Change.org, since signed by 2,500 people, demanding to know how the university is spending government money allocated for mental health services, how those services have changed over the past five years, and specifically how it has improved the student-to-counsellor ratio. “The point wasn’t to point fingers at the school, but I felt nothing would happen if there wasn’t push from students,” Ly says.

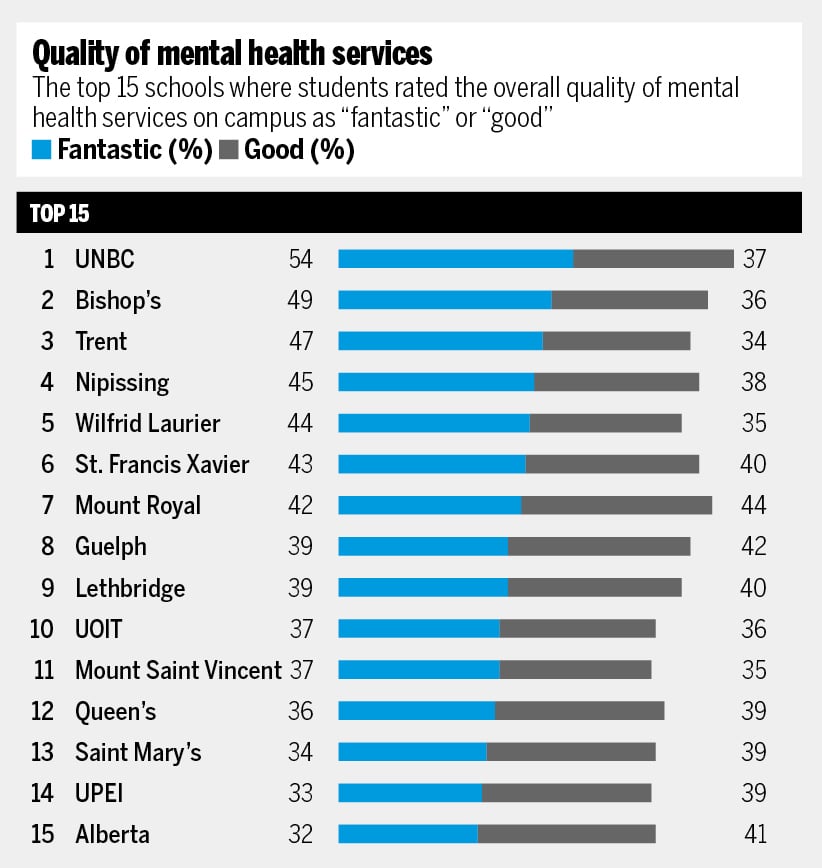

As the taboo around talking about mental health crumbles, students are demanding more resources on campus, and many post-secondary education institutions are struggling to keep up. When Maclean’s surveyed more than 17,000 students at almost every campus across the country last year, 14 per cent said they were in poor mental health, 10 per cent rated their school’s mental health services as either poor or horrible, and 31 per cent said their mental health was affecting their ability to succeed. Meanwhile, when asked what kept them up at night, several members of the Maclean’s presidents advisory board said at a June 2016 meeting that the demand for mental health services was weighing on their minds.

“The demand is increasing—and we take those demands seriously—but we’re not funded as a mental health services provider,” explains Christopher Manfredi, vice-principal (academic) of McGill University. “We’re funded as an educational institution. Trying to find the resources within our budget is a big challenge for us.” The other problem is figuring out when to reach out and when to let go. “What’s the balance between support and spoon-feeding?” asks Ollivier Dyens, McGill’s deputy provost of student life and learning. “This is a very delicate balance, and I haven’t found it yet.”

Among other things, McGill is trying out an initiative where if, say, a student is often distracted in class or frequently absent, a professor can send an “expression of concern” to the dean of students, who is tasked with following up and offering help if it is needed.

The University of Calgary, meanwhile, tapped anti-stigma expert Andrew Szeto to head its Campus Mental Health Strategy, which tries to identify mental health problems early and, by partnering with resources already available in Calgary, make sure help is available 24-7.

“What if students need services at 1 a.m.?” asks Szeto. “They can call in to the same line for the campus wellness centre and they have options to be directed toward services at the Distress Centre (a 24-hour support line) or Wood’s Homes (a non-profit children’s mental health centre).”

But campuses in smaller cities and towns simply don’t have the same community services to draw upon. At Mount Allison University in Sackville, N.B., (pop: 5,500) most of the few psychologists associated with the school’s wellness centre are based 50 km away in Moncton, N.B., according to Shaelyn Sampson, the Jack.org chapter co-lead at the school. And it’s a visit they don’t make every day. “I know one [psychologist] comes in Wednesday afternoons from about 2 p.m. to 6 p.m.,” says Sampson, who gets an hour every month or two. Allot one hour per appointment, and exactly four students get seen each week by that counsellor.

Sampson runs educational events each semester with Jack.org, a youth advocacy group with chapters across Canada, to promote positive mental health and break down the stigma that stops people from even talking about their own mental health.

When Sampson’s anxiety and depression reached the breaking point two years ago and she called the centre, she waited a month to get in. This semester? “We’re seeing wait times of six weeks and up to three months,” she says. “When a student is in a rough spot and having severe mental health issues, you don’t necessarily have three months.”

Some don’t even call, thinking someone else might need help more, Sampson adds. “You shouldn’t have to reach that breaking point to feel that your reaching out is valid.”

Feeling Overwhelmed

The top 15 universities where students reported feeling overwhelmed on a daily or weekly basis. In addition, the top 15 areas of study across all of the surveyed universities where students said they felt overwhelmed at a minimum of once every week and sometimes on a daily basis.

[rdm-footable id=’767′]

[rdm-footable id=’769′]