Damage control

Failing essays or assignments already? How to deal with a mid-term grade crisis

Share

Sarah had a slow start to her fall semester at UBC. She moved into a new apartment at the beginning of October, was waitressing part-time, and her boyfriend moved back to Vancouver and was taking up more of her time than usual.

But Sarah is a good student and is only taking three courses this semester instead of her usual five, so she was sure she could handle it. Then, in late October she got back the mark for her first assignment for her 400-level math class: she had failed. It came as a surprise to her. “I suspected that I may have done poorly,” Sarah says. “But I spent a lot of time on the assignment so I thought I’d at least pass.”

Now the semester is moving on and the workload in her courses has turned out to be enormous, and Sarah’s not sure if she can pull it together to pass her math class. What’s a girl to do?

Now the semester is moving on and the workload in her courses has turned out to be enormous, and Sarah’s not sure if she can pull it together to pass her math class. What’s a girl to do?

Meghan Houghton, the Associate Vice-Provost for Student Success and Learning Support Services at the University of Calgary says that mid-semester grade crises are very common, particularly among first year students, who haven’t necessarily adjusted to the higher expectations of university.

“We know there is a natural transition period for students,” she says. “Their ‘A game’ from high school is requiring some refinement and polishing in order for that to be an ‘A game’ for university.”

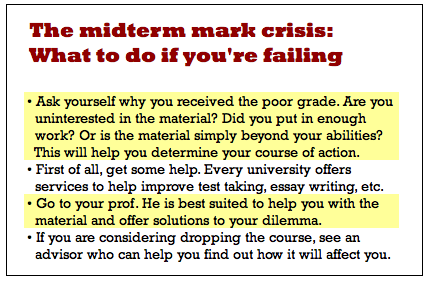

If you find yourself in this situation, you should first seek out the learning support services offered by their school and refine their study skills. UBC, for example, offers writing tutorials, peer academic coaching, help hiring a tutor and piles of online academic resources, among other programs.

Another common cause of bad grades for first-years, Houghton says, is a lack of interest in what they’re studying. “Low grades on the first round of exams may be reflective of low motivation to study whatever it is they’ve chosen to study.”

Excelling is difficult if you don’t like what you’re studying. So, your bad grades could be a sign that you’re pursuing the wrong degree, and if that’s the case, you should make a change sooner rather than later. Make an appointment with an academic advisor at your school and they’ll talk you through what program is best for you.

Sarah is no first-year, however; she only has a few semesters until graduation and she knows what degree she wants and that she needs to pass this math course to get it. But the workload for the course is extremely heavy and she thinks she might already be too far behind to catch up. Should she abandon the class to focus on her other classes? That would also give her time to pick up extra shifts at work to pay to take the course again next semester.

“I’m just getting my ass kicked,” she says. “My other grades are suffering because that class is so demanding.”

“I guess the prof just doesn’t realize that we have other courses we need to be spending time on,” she laughs.

There are other considerations at play, however. First of all, UBC’s deadline for withdrawing from a course and being given a “W” was October 16th — before she had received a single mark from her professor. A “W” would show up on Sarah’s transcript but would not affect her overall GPA. But because it’s too late to drop the course, a failing mark would drag her GPA down.

But at UBC, flunking with a 20 per cent mark or with 45 per cent are very different situations. The university’s system of grading rewards students for making an effort, even if they failed. “UBC calculates averages as a percentage, so a fail isn’t just a zero like it would be on a four-point GPA system. There are different degrees of failure,” Sarah says. If she walks away from the course, she’ll end up with a grade around 10 per cent. So, making an effort and instead flunking with 40 per cent will be better for her overall average.

If it’s not too late to withdraw from a course with a “W” standing, withdrawing can save your GPA from the black mark of a bad grade, and it can free up time for you to focus on getting better grades in your other classes.

Even so, it’s not always the best idea to withdraw — there are trade-offs. Unless you withdraw very early in the semester, you probably won’t get your tuition refunded to you. Also, you’ll land up having to either take the course again or take a different course as a substitute. If you go around withdrawing from courses willy-nilly, you’re going to add semesters and even years to the time it’s going to take you to get your degree. If you have student loans, you also have to be careful not to drop so many classes that you lose your full-time status, because Canada Student Loans may ask for part of their money back.

Seek out advice to find out how withdrawing from a course will affect your academic plan, your other classes and your transcript. Students, Houghton says, should “meet with an advisor to talk about what the implications of dropping a class are, and likewise what the implications of not dropping a class are.”

Before you drop the course, though, go and talk to your professor. The situation may not be nearly as dire as it seems, and your prof is usually the best person available to help you through whatever trouble you’re in.

Your prof knows the course material better than anyone, and he might be able to talk you through any troubles you’re having. He also knows what other resources might be available to help you, such as TAs, and peer tutors.

Some professors occasionally make deals with students who are sincerely interested in putting in the work to pull their grade up — for example, a prof might agree to disregard the terrible mark you got on your midterm if you get a good enough grade on your final.

In spite of this, many students never talk to their profs, especially first years.

“The reality is that faculty members often sit in their office hours without students approaching them for consultation,” Houghton says. “I find this deeply unfortunate given that they are most intimate with the materials and they are in the best position to help the students figure out how they might navigate that specific course.”

In the end, Sarah’s prof convinced her to tough it out and try to pass that math class.

Being an experienced student, she knows that he’s the best resource that’s available to her. “I’ve been in my prof’s office, like, everyday,” she laughs.

Erin Millar and Ben Coli are working on an advice book about going to college and university in Canada. Email comments and questions to [email protected].