Bright Idea: Touchscreen chamber for mice, complete with milkshake

A chamber that completely changes the way cognitive tests are performed on animals

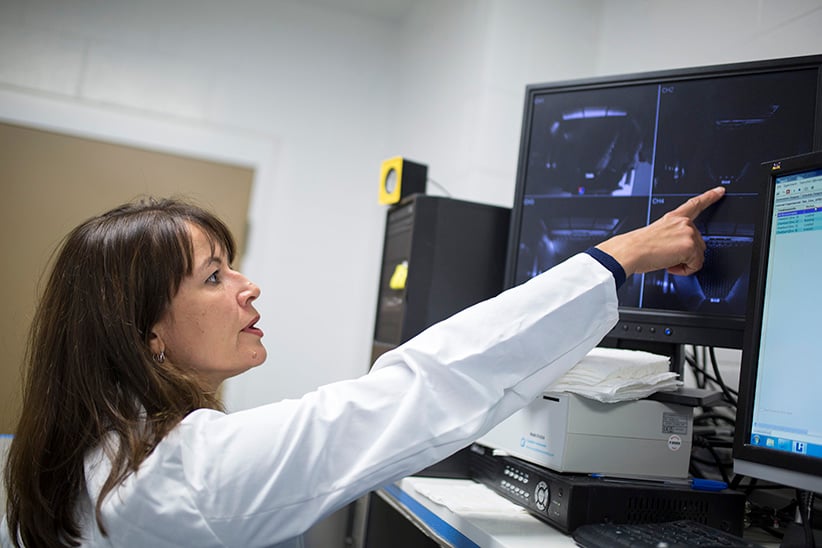

A mouse in the Bussey-Saksida touchscreen chamber at the University of Western. (Photograph by Nick Iwanyshyn)

Share

Great minds do not think alike, and that’s why universities and colleges are the mother of inventions. Click here for the rest of our Bright Ideas series.

Tim Bussey and Lisa Saksida: Western University

A metal box inside which mice play with an iPad and slurp strawberry milkshakes—is transforming the way cognitive tests are performed on animals. The goal, say the Western University neuroscientists who designed it, is insights into human disorders and new treatments for diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and schizophrenia.

The Bussey-Saksida touchscreen chamber is the brainchild of husband and wife team Tim Bussey and Lisa Saksida. The chamber is about the size of a toaster oven (there is a slightly larger version for rats) and its walls are soundproofed against distracting noises. Inside, a trapezoid-shaped box helps focus the mouse’s attention on the larger wall, which is mounted with an iPad. The smaller wall contains a milkshake delivery trough. The box can accommodate both wired and wireless sensors for tracking the mouse’s neural activity as it performs various learning and memory tasks. “What will appear on the screen is shapes or photographs,” says Bussey. “The mouse wanders up and touches the screen with its nose. If they touch the correct object, they hear a beep and they turn around to the back of the box where they receive a dollop of strawberry milkshake.”

For some tests, the “correct” object is the one it has not seen before—it must remember the objects it has already seen in order to distinguish the new one. The system takes advantage of a mouse’s innate drive to explore its environment by sniffing around and its interest in completely new things.

The chamber allows researchers to use the same cognitive tests on mice as they do on humans. Researchers usually test a lab mouse’s ability to remember and learn by dropping it into a maze set up in a tank of water. To avoid drowning, the mouse must navigate its way to a platform by remembering landmarks. Human cognitive tests usually involve pressing a finger to either remembered or novel objects and locations on a touchscreen.

Bussey and Saksida’s chamber allows the mouse to perform exactly the same test as a human. This means results from mouse studies can be directly applied to human-based clinical trials, says Adrian Owen, the Western University neuroscientist who lured Bussey and Saksida from the University of Cambridge to Western’s Brain and Mind Institute. “They can have a mouse in the chamber poking its nose at a touchscreen, remembering the location of objects around the screen. At the same time, right around the corner, I’ll have a patient with Alzheimer’s touching a touchscreen with their finger, doing basically the same test,” says Owen.

The box makes it easier to assess experimental treatments designed to enhance performance. If a treatment boosts a mouse’s ability to remember and learn, and mice and humans are assessed the same way, that treatment might help humans. And “it’s fun for the mouse,” says Saksida. “They want to get going.”

How to be a cognitive neuroscientist

Inventors: Tim Bussey and

Lisa Saksida

Positions: Bussey is Western Research Chair in cognitive neuroscience; Saksida is professor and scientific director of BrainsCAN at Western University. They’re also members of the Brain and Mind Institute, scientists in Robarts Research Institute and leaders of the Translational Cognitive Neuroscience Lab.

Undergraduate degrees: Bussey

has an honours B.Sc. in chemistry from the University of Victoria, 1984, and an honours B.Sc. in psychology from UBC, 1992; Saksida has an honours B.Sc. in psychology from Western, 1991

Graduate degrees: Bussey has a Ph.D. in experimental psychology from the University of Cambridge, 1995; Saksida has a master’s in biopsychology from UBC, 1993, an M.Sc. in artificial intelligence from

the University of Edinburgh, 1994, and a Ph.D. in the neural basis of cognition and robotics from Carnegie Mellon University, 1999

Other pathways: Undergrad degrees in psychology, biology or neuroscience; graduate studies in neuroscience

[widgets_on_pages id=”Education”]