Day 18 on the Trans-Canada, Saint John, New Brunswick

Trans-Canada distance: n/a

New Brunswick

Share

Trans-Canada distance: n/a

Actual distance driven: 4,504 km

THEN: In the earliest days of road travel through New Brunswick, the main highway led west down the Bay of Fundy from Moncton to Saint John, then turned north to pass through Fredericton and on up to Quebec.

It was only when the Trans-Canada Highway was being planned in the 1950s that Saint John was bypassed. Instead, the new TCH came halfway through from Moncton, then turned at Sussex and stayed north to take a more direct route to Fredericton. The 1949 Act that laid out the rules for the Trans-Canada said the highway should take “the shortest practicable route,” and that clearly didn’t include heading down to Saint John.

That route through Sussex, though, became known as Suicide Alley because it was often clogged with large trucks and far too many cars, all driving too fast between the two cities on two-lane roads that had not anticipated such volume of traffic. So in the 1990s, the government of New Brunswick obtained federal funding to help it put through an entirely new road: a four-laner, with centre medians so wide that oncoming traffic was often hidden behind broad stretches of woodland.

There was only one problem. This was an expensive highway to construct and the government didn’t have the money, so it announced there would be a toll charge to use the road.

I’ll be in Fredericton tomorrow. Catch up with me then to find out what happened.

NOW: When Dr. Perry Doolittle drove down from Moncton to Saint John in 1925, in the first few days of his cross-Canada road trip with a Model-T Ford, he stopped at “a silver fox farm near Moncton.” The film clip that became a record of his journey shows the foxes loose at the farm, and a couple of workers with them. You can watch it here.

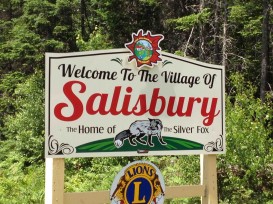

Salisbury, just off the Trans-Canada, is known as “the home of the silver fox,” thanks to the prolific breeding of foxes in the area at the turn of the last century. At one time, every farmer around kept foxes, raised for their pelts, and those pelts could fetch up to $1,000 each at the auction house.

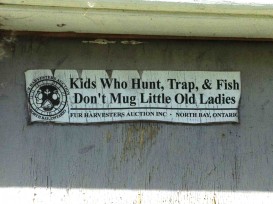

Not any more. Today, there’s only one farm left in the area, a small operation with about 800 foxes, and the owner is understandably nervous about talking to a journalist. Anti-fur activists are known to break into farms in the States and in Europe and release all the animals. But as Ron Steeves says, those animals are only used to life in captivity and die quickly in the wild, either from starvation or out on the road.

It’s hard work being a fox farmer, he says: “Nobody in their right mind would do what I’ve done, and I’ve been in the business 30 years now.” There’s no time off, and foxes are fickle animals, not simple to breed. “You could come home at night and just throw some food at them – and some people have no choice but to do that, to work another job – but I don’t call that farming,” he says.

“But I always liked the foxes. If you enjoy what you’re doing, then it really isn’t work.”

There was another nearby farm until recently, but when owner Bruce Williams died, nobody wanted to take it on. It now lies derelict.

The bottom dropped out of the industry in the late 1980s, Ron says, when fashion demands turned against real fur. Those thousand-dollar pelts sold for just $38 each in the early ‘90s, but the market has begun to return again with new demand from China and Russia. Now a pelt can sell for as much as $250, but there’s never a guarantee of price – fur farmers don’t have a marketing board to regulate prices.

Ron and his daughter Tina and partner Marilyn took me for a tour of the operation, but they didn’t want me taking any photos – while they’re proud of the standards they keep and the care they provide their foxes, they want to maintain a low profile. Ironic really, in “the home of the silver fox.”

SOMETHING DIFFERENT … I met Doug Sentell at the Salisbury Big Stop. He told me the history of fox breeding in the area, which morphed into a proud promotion of his town. And then I checked the spelling of his name.

“Two Ls at the end,” he said. “Make sure you get it right – there are only five of us in Canada.”

Only five? Is the name that unusual?

“Well, there’s me, there’s my cousin Frank, and then my son Peter and his two boys. There aren’t any others in this country. It’s an American name, I think. There are about 37 Sentells in the States, but that’s all.”

Doug’s been working at the Big Stop since it was opened in 1997, when his son helped design it for the Irvings. Ten years ago, he established a table staffed by volunteers that raises money for breast cancer research by selling raffle tickets toward a prize – right now, there’s a new Mini Cooper to be won.

“In nine years, that table took in a million dollars,” he says. “Last year, we raised $84,000 more. Pretty good for just a table and a couple of volunteers.”