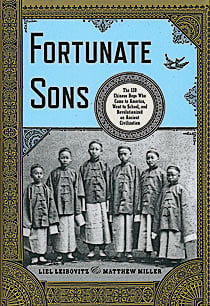

For a story that begins with a Hollywood ending, this intriguing take on China’s centuries-long efforts to engage the modern world comes to an ambiguous close. The 120 boys of the Chinese Educational Mission, 12- to 14-year-olds sent to America starting in 1872, were the spiritual sons of Yung Wing, a child brought to the U.S. by Western missionaries. In 1850, the first Chinese to enrol at Yale, 20-year-old Yung stood on the sidelines at the school’s annual proto-football game, a mass scrum that featured the freshman class (126 strong that year) versus the sophomores (123 in number). The aim of the essentially rule-free contest was to score, by brute force (the use of knives was not unknown), the single goal that would end the match. Dressed as befit his cross-cultural life—a Yale straw boater hat and the silk robes of a Confucian scholar—Yung was moved to action when the loose ball rolled near him. Grabbing it, he dashed for the goal. A sophomore tackled him, but Yung managed to kick the ball across the goal line, giving the freshmen a rare victory and himself a moment of American acceptance that was to prove fleeting.

For a story that begins with a Hollywood ending, this intriguing take on China’s centuries-long efforts to engage the modern world comes to an ambiguous close. The 120 boys of the Chinese Educational Mission, 12- to 14-year-olds sent to America starting in 1872, were the spiritual sons of Yung Wing, a child brought to the U.S. by Western missionaries. In 1850, the first Chinese to enrol at Yale, 20-year-old Yung stood on the sidelines at the school’s annual proto-football game, a mass scrum that featured the freshman class (126 strong that year) versus the sophomores (123 in number). The aim of the essentially rule-free contest was to score, by brute force (the use of knives was not unknown), the single goal that would end the match. Dressed as befit his cross-cultural life—a Yale straw boater hat and the silk robes of a Confucian scholar—Yung was moved to action when the loose ball rolled near him. Grabbing it, he dashed for the goal. A sophomore tackled him, but Yung managed to kick the ball across the goal line, giving the freshmen a rare victory and himself a moment of American acceptance that was to prove fleeting.

Back in China, Yung eventually found a patron who shared his vision of turning out Western-educated engineers, scientists and (especially) soldiers. His boys flourished at New England prep schools—one, the athletically gifted left-hander Liang Chen, even became a pitching ace and captain of the Phillips Academy baseball team. But by 1881, with more than 60 boys in university, including 22 at Yale and eight at MIT, the stresses working on the mission finally tore it apart. Suspicion at home that the boys were becoming too Westernized—two had converted to Christianity—combined with rising anti-Chinese sentiment in the U.S., led to the imperial court recalling them, cutting short a potentially fruitful meeting of East and West.