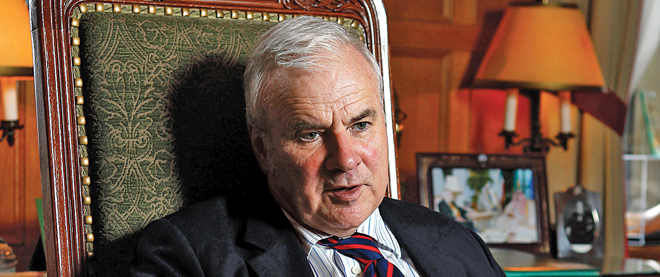

In conversation: Peter Milliken

How minority Parliaments lower the tone, why tossing out MPs fails, and his favourite Scotch

Photographs by Blair Gable

Share

When the House of Commons resumes sitting this week, the first order of business for MPs will be electing a new Speaker. It will seem strange not to have Liberal Peter Milliken striving to keep order from the big chair. Milliken, 64, didn’t stand for re-election in his Kingston, Ont., riding this spring, ending his record decade-long run as Speaker. Maclean’s spoke to him in the elegant wood-panelled office he’s now leaving, sitting under a large framed print of Yousuf Karsh’s famous wartime portrait photo of Winston Churchill, which was taken on that very spot.

Q: When did you first become interested in the goings-on of the House of Commons?

A: The first visit I remember would have been in Grade 7 or 8. After I got into high school, my cousin John Matheson got elected from Leeds, right next door to Kingston. Once I got my driver’s licence, I started to come up to visit. He told me I could subscribe to Hansard and I started in 1962. I might have been 16. It was that period when I started following what went on in the House.

Q: Did you think at that time that you wanted to be an MP?

A: I can’t remember. Probably. Certainly the whole idea of the job interested me. I worked here in the summers of 1967 and 1968 for George McIlraith, who was the government House leader when he hired me, but was public works minister when I worked for him.

Q: Let’s jump ahead to 1988. You’d been a lawyer in Kingston and you defeated a big Tory name, Flora MacDonald, in that year’s election. How early in your time as an MP did the Speaker’s job start appealing to you?

A: It occurred to me in 1988. Not that I had any hope of making it. But the idea of trying did occur to me. I remember being discouraged by my whip. Obviously, I didn’t think other members were going to vote for someone they had never met.

Q: You eventually won in 2001.

A: I’d been deputy Speaker already, so I had some experience in the chair. I think other members were comfortable in supporting me for the speakership.

Q: And your long run as Speaker began. How has the atmosphere in the House changed over the years?

A: I think minority Parliaments tend to be more partisan. Parties are trying to score points over the others constantly. They want to get up in the polls [in case] there’s an election call. In a majority Parliament, you don’t normally have that degree of partisanship because you don’t have all the points to gain on immediate tricks in the House. There tends to be a more substantial policy differential that you exploit in argument. One hopes that with a majority Parliament the level of partisanship will decline somewhat.

Q: What were the crisis points that stood out as particularly challenging to you?

A: Hard to say. Certainly the media have made big plays of my rulings on production of documents, two of them. But, in a majority House, you wouldn’t have had those issues come to the Speaker at all. You wouldn’t have had a demand to the government, passed by the House, that the government wasn’t prepared to meet. So I think that while [the rulings] have some importance in terms of the privileges of the House, you wouldn’t even have these issues come to the chair in a majority situation.

Q: The House has been raucous in recent years. Beyond traditional heckling and haranguing, did you worry question period exchanges have declined below what’s reasonable?

A: In a minority Parliament, there tend to be a lot more shots taken by one party at another, whether it’s in the question or in the answer. That’s what’s going on. In a majority Parliament you wouldn’t see that as often, in my experience.

Q: But even the time MPs are given to make statements before question period, which used to be innocuous, is now sometimes stridently partisan. Should that be allowed?

A: It’s caused some trouble in the House, for sure. It was there so members could say something about somebody who had died in their riding, or won an award in their riding. Something significant at the local level. It’s turned into attack statements. They could abolish them completely and I don’t think it would make a big difference now.

Q: Many proposals for reforming the House have been floated. For instance, some say we should adopt the British practice of designating one day for the prime minister to answer questions. What do you think of that?

A: It lets the prime minister off the hook four days a week. I don’t think it’s an improvement. Having the prime minister there three or four days a week and choosing what to answer is, from my point of view, worthwhile. If I were in the opposition and the prime minister wasn’t answering, I’d make something of it after—I’d say, “I asked the prime minister questions and he wouldn’t answer, dumped it on a minister.”

Q: What about calls for encouraging more substantive QP exchanges by allowing questions and answers longer than the current time limit. Isn’t 35 seconds just too short?

A: It’s not too short. What they want is time to make statements. You should be able to ask your question in 35 seconds. You might not be able to make all the statements you’d like to make in addition, but I don’t see that we need statements as well. It may be harder for those giving answers to squeeze in all they’d like to say. On the other hand, what they’re saying is sometimes irrelevant to the question. It’s a game. The 35-second rule isn’t a big problem. In my view, it works well.

Q: Did you ever throw an MP out of the House?

A: I’ve never done it. It’s happened with at least one of my deputy speakers, if not two.

Q: But why not throw out MPs more often when they get out of line?

A: Before I was Speaker, I said one of the problems with this practice of giving the Speaker the power to throw a guy out is that he’s out of the chamber for a day. No rights or privileges suspended. He gets paid. He can fly to Vancouver. He can go to work in his office. He can go to caucus meetings. He can go and have a press conference in the foyer.

Q: What would be a better punishment?

A: My urging years ago, when I was not Speaker, was the guy should be thrown out of the Parliament Buildings, not allowed in for the rest of the day. All travelling privileges suspended and his pay docked for the day. Then the guy would start listening to what the Speaker says. Otherwise, you just make a saint of the person. He can hold a press conference and say, I called the prime minister a liar, or whatever the offence was, and I was right. Blah, blah, blah. He’ll get more media coverage if the Speaker threw him out. It’s not a very effective penalty.

Q: You’re known for trying to keep up social contacts among MPs across party lines. What do you do?

A: I have dinners for MPs, 30 or 40 at a dinner every two weeks or so when the House is sitting. I mix them up at a table.

Q: That sort of socializing among MPs from different parties is rarer than it was in earlier eras, isn’t it?

A: The change in the hours of sitting has had a significant effect. Members used to go up to the parliamentary restaurant to eat between six and eight when we had night sittings. Needless to say, they sat there with members not of their own party and chatted and maybe had a drink. It helped people get to know one another and be respectful to one another. So getting rid of the night sittings really altered the way the place operated. Plus, the lunch hour is gone. They took away the night sittings and added two hours [of sitting] at lunchtime. So lunch is served in the lobbies. Well, you don’t mix in the lobbies.

Q: Is the place less fun now than in your early years here?

A: I guess less fun is probably a fair description.

Q: Do you think it’s up to the party leaders to set a better tone, and were there any who you felt lowered the tone?

A: Certainly the leaders have a significant influence. If their tone is down it will lower the tone for the others. There won’t be many members who are going to strive to be better than their leader in terms of their approach to issues in the House. It’s a difficult one. I don’t think there were any particular members, certainly I wouldn’t name any.

Q: Why not?

A: Well, I just don’t think it’s appropriate to do so. As I’ve said, I think the tone in the House was down in the minority. So you could get away with more and no one was going to object because everybody wanted to do the same thing.

Q: You blame all parties, then.

A: It got to that point. There may have been people who had an interest in a better tone at the start. But as things went downhill they pitched in too.

Q: I’m told you’ve at least raised the quality of the wine and Scotch served in the Speaker’s dining room.

A: I don’t buy expensive bottles, but I choose it all. Sometimes I’ll load my car up with 20 cases in Kingston and bring them up.

Q: What’s your favourite Scotch?

A: I drink almost any of them, but there’s a Speaker’s Selection by Dalwhinnie. That was voted in by the members of Parliament at a whisky tasting. It’s a single malt, but a reasonably bland one, compared to the one we had before, which was a Talisker. It was much peatier. I’m happy either way.