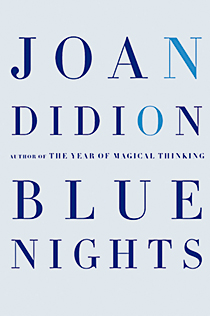

Blue Nights is a continuation of Joan Didion’s rumination on grief that began with The Year of Magical Thinking, written following the death of her husband, John Gregory Dunne, eight years ago. The new book is an inquiry into her relationship with her daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne, who died less than two years later, at 39, following an avalanche of medical crises. Didion is now 76, and Blue Nights also stands as her interrogation into being old, frail and alone (“Whole days now spent on this one question, this question with no possible answer: who do I want notified in case of emergency?”). First the husband, then the daughter, soon the author herself—it could be a real downer. Yet Didion once again turns a gimlet eye on this latest biographical tranche—holding events up to the light, examining them this way and that, judging herself as a mother (and finding herself wanting), searching memory for meaning, occasionally engaging the reader head-on (“Let me again try to talk to you directly”).

Blue Nights is a continuation of Joan Didion’s rumination on grief that began with The Year of Magical Thinking, written following the death of her husband, John Gregory Dunne, eight years ago. The new book is an inquiry into her relationship with her daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne, who died less than two years later, at 39, following an avalanche of medical crises. Didion is now 76, and Blue Nights also stands as her interrogation into being old, frail and alone (“Whole days now spent on this one question, this question with no possible answer: who do I want notified in case of emergency?”). First the husband, then the daughter, soon the author herself—it could be a real downer. Yet Didion once again turns a gimlet eye on this latest biographical tranche—holding events up to the light, examining them this way and that, judging herself as a mother (and finding herself wanting), searching memory for meaning, occasionally engaging the reader head-on (“Let me again try to talk to you directly”).

She writes quietly, emphatically. And yet sorrow leaks from every page. “I can now afford to think about her. I no longer cry when I hear her name.” Perhaps out of delicacy, Didion offers little about her daughter’s death, but rather what we need to know about her life. We learn that Quintana Roo was adopted in 1966, named for the Mexican territory, now a state. A precocious child and a depressed, anxious adult, she was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. For a time, she was the photography editor at Elle Decor. She was married shortly before her father’s death, shortly before she was comatose in the first of four ICUs she would visit in the last two years of her life. A more telling picture comes through the details—the imaginary Broken Man who frightened her as a child, the novel she wrote as a teenager “just to show you (how sad for an adopted child to feel she has to live up to the expectations of accomplished parents).” The title, Blue Nights, is a reference to those days in late spring when the lengthy twilights of the coming solstice signal that the days are growing longer, writes Didion. Blue nights carry their own warning: “I found my mind turning increasingly to illness, to the end of promise, the dwindling of the days, the inevitability of the fading, the dying of the brightness.”