Editorial: Federal leaders must act—the fight for Canada is on

If the party leaders do not succeed in making unselfish co-operation a positively sacred principle, the future of Confederation is not safe

Christinne Muschi/Reuters

Share

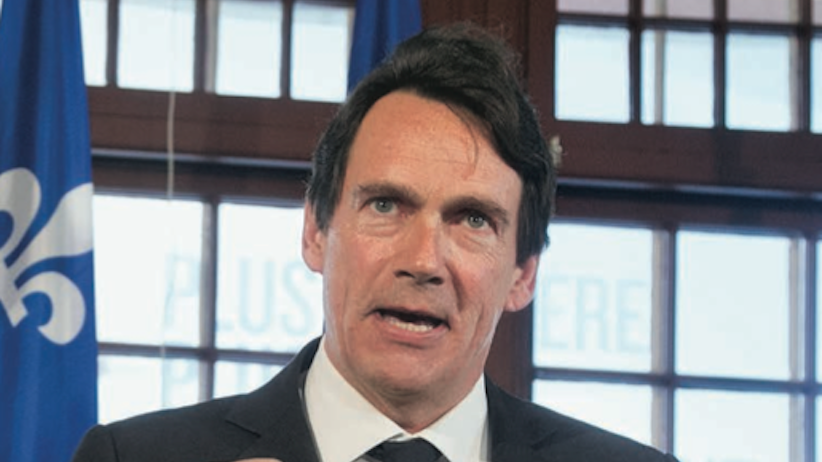

That was some firework Pierre Karl Péladeau set off. The French-Canadian media magnate’s sudden announcement that he would run for the Parti Québécois in April 7’s provincial election had effects on . . . well, let’s count. Most obviously it will influence the landscape of the election itself, for “PKP” is considered to be Quebec’s biggest current business star. But Péladeau’s own business interests immediately went into limbo, with the candidate sending mixed messages about what kind of trust he would park them in. This, in turn, creates questions about the freedom of news reporting and political expression in Quebec, which has suffered somewhat from Péladeau’s touchy hegemony.

Péladeau’s public embrace of separatism created problems for Sun Media’s conservative-chauvinist interests in English Canada. It added another scar to the reputation of his long-time mentor Brian Mulroney. It may compromise the ability of Péladeau’s Quebecor empire to land a second NHL franchise for Quebec. It will hurt the Parti Québécois’s reputation with organized labour, who regard Péladeau as Satan. It gives Premier Pauline Marois a front-bench star, and perhaps some extra credibility with business leaders. But it also puts her in the shadow of an unpredictable, electorally untried, awesomely powerful colleague who may be the most obvious successor if she underperforms at the ballot.

In short, Péladeau’s change of vocation has potential for a dazzling array of impacts on Quebec’s political scene, its economy, and its history. When all is said and done, he may end up as the man who shattered Confederation—or the one whose egotistical meddling saved it. These are exciting times.

Exciting times, it should be added, are not what Canada was asking for. It is not as though the Quebec election did not come with sickeningly high stakes already. Any parliamentary majority for Marois would enable her to pass the controversial values charter that forbids public servants from displaying religious symbols in the workplace. A stronger mandate would open a path to Quebec Referendum III.

The scary part is that the math in a three-sided race is very unstable, and the outcome of the election will be hard to predict even if the polls can be trusted. It is not just that a one- or two-point difference in the PQ’s vote share could make or break a PQ majority. It is worse than that: a nigh-imperceptible twitch in Coalition Avenir Québec votes could also make the difference by squeezing the Liberals. Campaigning is certain to continue at hurricane force until the last second.

Our federal leaders ought to be, and clearly are, preparing for the worst. The Prime Minister, who is unpopular in Quebec, reached out last week and met privately with NDP Leader Thomas Mulcair and Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau. If there is a Referendum III, these Quebecers will be needed to participate in a popular front for the Non side, and not casually. Mulcair, by far the most popular politician in Quebec, will probably have to take the lead. Trudeau, who carries more metaphorical baggage in Quebec, must be encouraged to play narrowly to his strengths—and must be content to do it, too. Prime Minister Harper’s most important job will probably be letting these men make fairly free use of his party’s organizational and marketing sophistication.

National unity is an essential precondition for the ambitions of all these leaders. They will all sincerely want the Non side to win. Good intentions won’t be enough. It will be difficult for them to find equilibrium, to resist looking beyond the referendum and playing for advantage in later federal elections. If the party leaders do not succeed in making unselfish co-operation a positively sacred principle, the future of Confederation is not safe.

This should start with mutual determination to seek a clear, short ballot question in a separation referendum. The case of September’s Scottish referendum on independence is instructive, and should be emphasized. The nationalists were able to agree with the government of the U.K. very quickly on a six-word question, “Should Scotland be an independent country?” Yes will probably lose over there. But if Yes wins, no one can doubt what it means.

In general the Scottish independence debate has had some impressive features. British parties and institutions have not been afraid to discuss the consequences of breaking up the state, particularly on monetary and employment fronts. They have not been content to let Scottish separatists push problems forward into a hypothetical future negotiation process.

Our federalist politicians need to fight the creative use of ambiguity by Quebec nationalists. The ballot question is particularly important: Confederation has already been hazarded on absurdly vague ballot language twice. (1995’s ballot mentioned a “formal offer to Canada” for a “new partnership,” but Jacques Parizeau later admitted that a Oui victory might have been followed by a speedy declaration of independence.) The Supreme Court’s ruling in the 1998 Quebec secession reference insists on a “clear question”, but it also emphasizes that the Court cannot draw a flowchart of simplistic referendum rules. The politicians, federal and provincial, have to decide it amongst themselves. But if six words are enough for Scotland, why should Quebec need more?