Tonight’s special: nostalgia, with a side of authenticity

Everything old is new again in the food world

Share

While I was trying to think of a food-related idea to pitch for Maclean’s upcoming innovation issue, something occurred to me: there aren’t any, unless you count nostalgia as an innovation. Think about it: Denmark’s Noma, voted the best restaurant in the world last year, fashions most of its dishes from ingredients that have been foraged from the woods. Plus, it’s practically mandatory for all new restaurants to display homemade jars and cans of preserves on (ideally wooden) shelves, just like grandma had. (You’ll also find preserves in the pantries of any self-respecting 30-something food hound, myself included.) And the farm-to-table trend, not to mention the desire to find the most authentic of everything—from pizza to pasta to Peking duck—is so widespread it deserves parody.

While I was trying to think of a food-related idea to pitch for Maclean’s upcoming innovation issue, something occurred to me: there aren’t any, unless you count nostalgia as an innovation. Think about it: Denmark’s Noma, voted the best restaurant in the world last year, fashions most of its dishes from ingredients that have been foraged from the woods. Plus, it’s practically mandatory for all new restaurants to display homemade jars and cans of preserves on (ideally wooden) shelves, just like grandma had. (You’ll also find preserves in the pantries of any self-respecting 30-something food hound, myself included.) And the farm-to-table trend, not to mention the desire to find the most authentic of everything—from pizza to pasta to Peking duck—is so widespread it deserves parody.

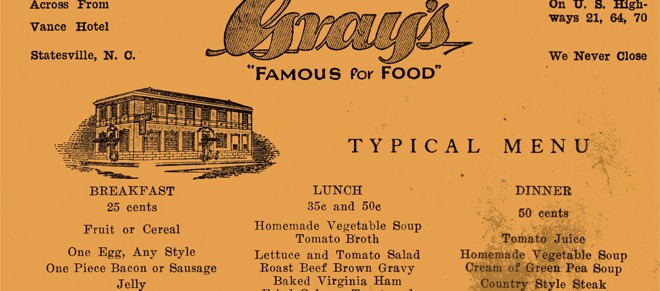

Everything old is new again—right down to the menus. And I mean the actual menus: several restaurants in the U.S. now specialize in serving dishes made from vintage menus, like Next in Chicago: you can’t actually call the restaurant, which opened in April, to make a reservation but you can buy a ticket online to book one of their 62 seats and eat from their menu, which is fashioned after a particular time and place, and changes four times a year. The first one featured dishes from Paris circa 1906. There’s also San Francisco’s the House of Shields that opened in December of last year in a 102 year-old house. They’ve turned to old books for menu inspiration (the website even boasts, “In keeping with tradition, there is no clock on premise. Nor is their a T.V.”) Virtue Feed & Grain in Virginia dishes up Irish pub classics, with a modern wink. And one of last year’s best selling cook books, The Essential New York Times Cookbook, features over 1,000 recipes spanning 150 years from the paper’s archives. (I bought it for myself around Christmas, but still haven’t made the tomato soup, courtesy of a recipe from 1877.)

Let me be clear here: I’m not opposed to historic menus and recipes. Nor, apparently, is Danny Meyer, the brains behind Manhattan hallmarks like Gramercy Tavern and Shake Shack. In a recent New York Times Magazine profile of the extremely successful restaurateur, there’s a scene where he’s leafing through menus from the 1920s and 30s looking for inspiration for his new Battery Park City restaurant. (It’s also revealed that he has his own collection of historic menus.) And I cannot wait until the New York Public Library finishes their epic What’s on the Menu project that’ll see thousands of dishes transcribed from their vast collection of archived menus—one of the largest collections in the world actually—and made available to the public in a searchable database (there are currently 520,258 dishes transcribed from 9,309 menus).

Maybe this food trend towards all things nostalgic was inevitable: I mean, what sort of food innovations are left post-El Bulli? And I for one look forward to eating a meal that was once enjoyed by the upper crusts on the Titanic at a future Titanic-themed restaurant. (And if one doesn’t open up, I can whip it up at home because there is a cookbook. For real.) Or maybe we’ll get to sample a meal that Henry V enjoyed, preferably in a castle with no plumbing: it’s recorded that he decided on whale and porpoise being served at the coronation dinner of his queen. (Sadly, it’s not recorded whether or not he liked the mammalian feast but Henry VIII is known to have enjoyed both, porpoise a little more than the whale.) I just hope some of these restaurants, bound to be opening soon, make period dress mandatory because I want to bust out my chaps, cod piece and corset—not all at once, of course, unless it’s a cowboy-Victorian-Tudor-themed restaurant. Now that, I could get behind.