B.C. fires stir memories of Fort McMurray—and fear for the future

The evacuation of Williams Lake shows lessons of last year’s nightmare sank in. Good thing, because the wildfire threat across Western Canada is getting worse.

Cars and trucks drive though the thick smoke caused by wildfires just outside of Kamloops, B.C., on Sunday, July 16, 2017. Over a hundred wildfires are burning throughout British Columbia, forcing thousands of residents to be evacuated or placed on evacuation alert. (Jonathan Hayward/CP)

Share

For Walt Cobb, the scariest moment came Sunday morning, when the White Lake fire threatening Williams Lake—one of 159 wildfires raging across B.C., and 15 threatening communities—jumped the Fraser River just west of the central Interior city of 10,000. The day before, as winds gusted to 70 km-h, three fires joined into one raging inferno, 13,000 hectares in size.

The fires had begun 10 days earlier, when a night storm blew through the area—“so fast it barely left a skip of rain,” says Richard Boston, who works in the local mining industry. “But dry lightning had done damage,” he adds. “Driving to work the next day, I could see puffs of smoke everywhere.”

Boston, who fought fires in his late teens and early twenties, kept a close eye on the smoke plumes, packing a bag for himself and his daughter in case they needed to flee. Friends of Boston’s had been caught in last spring’s panicked, traumatizing rush to escape Fort McMurray; they were among those forced to drive through towering flames to escape the northern Alberta city of 90,000. Boston wanted to avoid that at all costs.

Fort McMurray’s evacuation was also top of mind for Cobb, who is the mayor of Williams Lake: “That’s exactly what we were trying to avoid,” he says. “We did not want to see that again.”

So by Saturday, with “fire was blocking the road north, and the only way out of town to the south,” Cobb, the city’s fire chief and its chief administrative officer decided to order the evacuation of their city: “We felt it was necessary to get everyone out safe while we still could. Otherwise, we’d be trapped, with no way out.”

Boston was among the first to hit the road for Kamloops, typically a two-hour drive through the Cariboo region, that took some residents as many as nine hours overnight Saturday.

What Mayor Cobb didn’t know at the time was how narrowly the city would avert a complete disaster. Cobb learned yesterday that when the wildfire leaped the Fraser on Sunday morning, it began hitting speeds of 40 km-h. Flames were soon visible from city’s downtown. Fire officials say the only thing that saved the city was the direction of the wind, which happened to be gusting west that day, towards the fire. Had the winds been blowing east, the flames could have engulfed the city in less than a half-hour.

Cobb, who remains in Williams Lake, living in an RV “three steps from the fire hall,” is feeling a bit more optimistic than he was on Sunday. But “maybe that’s because you can only panic for so long,” he adds. “After a while, you get used to it.”

That pretty much sums up the mood in B.C., which has been under a state of emergency—the first in 14 years—since 8:15 p.m. Friday, July 7. The entire southern half of the province is at either an “extreme” or “high” risk of a wildfire start. And this isn’t the end of it, Cobb adds. “Far from it.”

This point in July generally marks the start of B.C.’s fire season. “But dryness, and a lack of rain have made [the B.C. Interior] a tinderbox,” he says. “Let’s just hope this isn’t just the beginning of something drastic.”

So far, some 55,000 people have been evacuated in B.C. And almost 190,000 hectares have already burned this year, well over the annual average of 154,000. Emergency planning officials are gearing up to be in response mode for another 60 days, what could be a sign of what summers here will be like going forward, where B.C. forced to spend a half-billion dollars every year to stop flames from swallowing communities.

RELATED: How just one of the B.C. wildfires compares to several Canadian cities

People here don’t yet understand the long-term impact these fires will have on Williams Lake and the surrounding communities, says Marie Hicks: “Life as we know it is gone.” Firefighters are fighting to save two of the area sawmills, the lifeblood of the local economy, she says, but the pine beetle had already destroyed so much of the surrounding forests, and the mills were running out of supply long before the fires started. The closure of even one will “decimate the local economy.”

Marie’s husband, Doug blames the beetle for the fires. Indeed, tens of millions of trees are dead or dying across Western Canada, thanks to insects like the pine and fir beetle, and the warming that has taken place over the last decade; it’s been the hottest, continent-wide, since the weather began being reliably tracked 140 years ago.

These days, it’s so bad, Doug says, it’s hard to find a living pine tree in the forests surrounding Williams Lake. Like a lot of people in the area, he’s taken to carrying a chain saw with him whenever he travels back roads, in case winds pick up. When they do, dead pines come crashing down, often blocking the roads. He says the provincial government isn’t doing enough to clearing up the deadfall—“fuel,” he calls it.

The hotter weather is both drying the forest—which is full of deadfall and standing, dead pines—and producing more lightning, says Ed Struzik, author of Firestorm: How Wildfire Will Shape Our Future, and fellow with the Institute for Energy and Environmental Policy at Queen’s University. This means fires are burning bigger, hotter, faster and more often, Struzik says. This is creating the perfect storm in Canada’s west. All wildfires need three things to burn: ignition, fuel, and the right climate. In Canada, wildfires that burned more than 200,000 occurred only four times between 1970 and 1990. This summer will mark the 13th time this has happened since.

For B.C., the annual cost of fighting these fires has jumped from $182-million a few years ago, to $300-million in 2014 and 2015. Western Canada, of course, has no monopoly on the trend.

Wildfires triggered evacuations and destroyed dozens of homes in California this month, and Arizona recently declared a state of emergency. Crews are fighting active wildfires in Nevada, Oregon, Washington and Montana; and last month, wildfires in Portugal killed 62. Many of them were burned in their cars as they attempted to outrun towering flames. France, Greece, South Africa and Australia have all fought similar outbreaks.

Marie says say several homes in their subdivision outside 108 Mile Ranch, south of Williams Lake have burned, but they don’t yet know the fate of their own home, a log cabin. For now, all they can do is hope. What’s making things easier is the generosity of people in Kamloops, says Marie: “We can’t walk down the street without being given a muffin or a bottle of water.” And their hotel bent the rules to allow them to bring Molly, their 70-pound black-and-white Border Collie mix, with them (Doug has to carry Molly in the elevator, which terrifies the 12-year-old dog).

Still, Marie is far more worried about her neighbours. “There’s a lot of poverty” in the region she says—“people who just don’t have a lot. Take away what little they do have, and there isn’t much left.”

B.C.’s wildfires are also top of mind for many of the victims of last spring’s fire in Fort McMurray, who have been anxiously tracking news of fires spread in B.C. They’ve got some advice for their British Columbian neighbours, starting with the practical: “Scan your photos and documents, and put it all on a stick you can carry in your purse,” says Sarah Abercrombie, who lost her home to fire last year. Her husband, Scott advises potential evacuees to take photos or a video of the contents of their home, which will make a potential insurance claim much simpler.

“Take it one day at a time, and talk,” Sarah adds. “Talk about how it felt. Describe every little detail. Let yourself cry, be angry. But don’t give up. Just breathe, and let folks help you. It’s okay to say you need help. And be grateful you are alive.”

“Remember: It’s just stuff,” says Fort McMurray resident, Nicci Deleeuw. “It can all burn as long as nobody gets hurt. You can, and you will, rebuild and start over.”

That’s how Assta Seto, a refugee from Liberia, who moved to Williams Lake last year, sees it. She fled Liberia in 1990, during the country’s civil war, and spent the following 27 years in refugee camps in Côte d’Ivoire, mostly in Danané. Seto raised her daughter there; and her three granddaughters were born there, before the family finally made it to Canada last year.

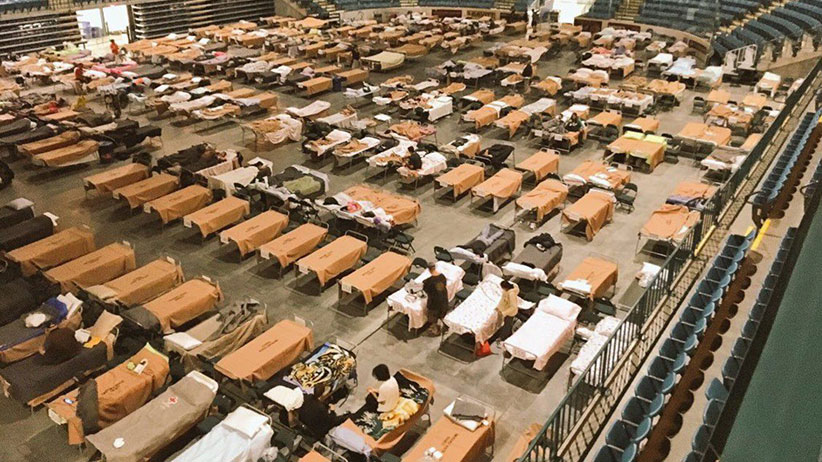

“I’m praying to God the fire goes down,” she says, speaking outside Kamloops’s Sandman Centre hockey arena, where she has been staying, sleeping on cots with her family. “I’m from a war country. I suffered, I suffered. I’m just so happy to come to Canada. It’s hard. But we’re all here. We’re going to be okay.”

MORE ABOUT B.C. WILDFIRES:

- B.C. wildfires stretch firefighters and evacuation centres

- B.C. wildfire evacuees welcomed into British Columbian homes

- B.C. communities brace for wildfire evacuation orders as weather turns

- The science and logistics of battling B.C.’s wildfires

- B.C. wildfires: Snapshots of the fires—and their aftermath

- B.C. wildfires: The race to save farm animals from the flames

WATCH MORE: Fort McMurray fire anniversary: We’re not just oil, we’re a community