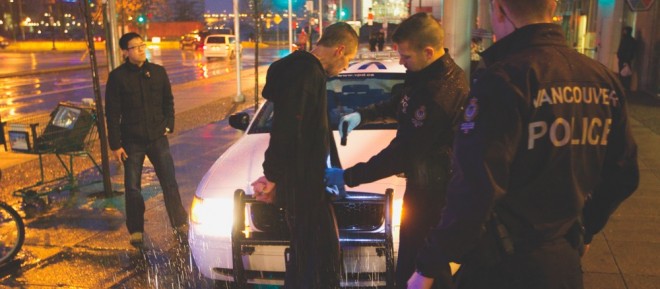

Canada’s most dangerous cities: Vancouver’s crackdown on crime is paying off

Police chief Jim Chu on his six-step approach to a safer city

11-27-11-Vancouver, B.C.– Crime reduction story

Share

For all of Vancouver’s über-green, laid-back urban vibe, it has a Wild West attitude toward crime. Gangs, drugs and troublemakers from the East account for the occasional shootouts and alcohol-fuelled riots, and they certainly explain why the city’s violent crime score last year was 55 per cent above the national average. That said, Vancouver is actually a crime-fighting success story. It has gone in the span of a decade from having some of the worst violent and non-violent crime scores in Canada to become one of its most improved. Its overall crime score plunged 49 per cent in 10 years, more than twice the rate of improvement of the country as a whole. Only the historically peaceful communities of Kawartha Lakes, Ont., Quebec City, and Roussillon, Que., south of Montreal, fared better or as well. Among the keys to Vancouver’s success are a series of crime-busting initiatives. Vancouver Police Chief Jim Chu was happy to explain:

For all of Vancouver’s über-green, laid-back urban vibe, it has a Wild West attitude toward crime. Gangs, drugs and troublemakers from the East account for the occasional shootouts and alcohol-fuelled riots, and they certainly explain why the city’s violent crime score last year was 55 per cent above the national average. That said, Vancouver is actually a crime-fighting success story. It has gone in the span of a decade from having some of the worst violent and non-violent crime scores in Canada to become one of its most improved. Its overall crime score plunged 49 per cent in 10 years, more than twice the rate of improvement of the country as a whole. Only the historically peaceful communities of Kawartha Lakes, Ont., Quebec City, and Roussillon, Que., south of Montreal, fared better or as well. Among the keys to Vancouver’s success are a series of crime-busting initiatives. Vancouver Police Chief Jim Chu was happy to explain:

ConAir

Think of “Get outta Dodge” taken to the jet age. Fugitives with outstanding warrants in other provinces or cities have a habit of fleeing west to start their criminal careers afresh. Unless the warrant is for murder or other major mayhem, their home jurisdictions are often happy to saddle Vancouver with the problem. A plan was hatched to give cons with outstanding warrants an all-expenses-paid, escorted flight back to the scene of their crimes to face justice. Some of the cost of airfare comes, appropriately enough, from provincial funds forfeited from proceeds of crime.

To date, 96 people have been transported out of province: 37 to Ontario, 33 to Alberta, 11 to Manitoba, seven to Nova Scotia, four to Saskatchewan, three to Quebec and one to the Yukon. As an example of the payoff, Chu cites a con with a drug habit of about $300 a day. Assume he gets 10 cents on the dollar for the goods he steals to support his habit, says Chu. “So, 15 grand a week is not out of the question for the kinds of crimes that guy had to commit.”

Ganging up on gangsters

When hunting high-value gangbangers, it often pays to aim lower than charges for murder or drug importation. Sometimes the entry point into a gang bust is turning their source of guns, or their customers for drugs, or, in one case, promising an abused girlfriend protection in exchange for co-operation. “We would get them for any crime we could,” says Chu. New provincial anti-gang laws are another tool. One prohibits retrofitting vehicles with hidden compartments, armour and bullet-proof glass. Another law requires health care facilities to report gun and stab wounds. Civil forfeiture laws have streamlined seizure of proceeds of crime. And Bar and Restaurant Watch programs use bouncers, backed by a police squad, to keep gang members out of the hot night spots and high-end restaurants they favour. “It’s making it less fun to be a gang member, which is good,” says Chu.

Crime analysis and public flogging

Chu remembers when crime analysts were “really old cops who put pins on maps.” Today those in the department have advanced degrees. They do real-time analysis, adding statistical performance measures for investigators, redeploying resources to hot spots and even predicting where crimes may occur. The bottom-line performances of commanders and patrol team leaders are compared against other districts at regular meetings, he says. “It’s not completely a public flogging but it’s powerful accountability.” He credits crime analysts mining data for playing a huge role in the arrest in December 2010 of Ibata Noric Hexamer, a Vancouver political organizer charged with a string of violent sexual assaults against girls as young as six.

Try a little tenderness

Property crime, much of it fuelled by addiction, has been a plague in Vancouver. Surveilling chronic offenders and gathering evidence of “the full nature of their offences” to present to judges is the first step to gaining longer sentences. The next move is more social worker than beat cop. Detectives visit offenders in jail and discuss the needs for their release, whether it be detox, housing or other social support to stop their cycle of crime. “We’ve got some very creative, compassionate detectives who build up a rapport with these guys. I’ve gotten emails and letters saying, ‘Hey chief, detective so-and-so was just great with me. First guy that cared about me in years. I’m doing better now because of what he did for me.’ ”

Bridge building

Vancouver police launched SisterWatch with groups representing vulnerable women in the Downtown Eastside. Improved relations are gradually overcoming a belief among women there—born of tragedies like the missing women’s case—that predators operate with near impunity. More women report assaults or provide tips now that they have evidence their claims are taken seriously. “It’s the legacy of Robert Pickton,” Chu says of SisterWatch.

Wanted Posters

It worked in the Old West, it works today. On a wet November day, Vancouver police and a corps of volunteers distributed 35,000 posters with photos of 104 unidentified people wanted in connection with the Stanley Cup riot last June. “Of 104 we got good tips on pretty much half of them,” says Chu. (His determination to see hundreds of rioters face charges will likely boost Vancouver’s 2011 crime rate.) The department also reaped a harvest with the latest ConAir 10 Most Wanted poster displayed on its website and elsewhere. Nine have been arrested. As for No. 10? Harold Richard Lambert, wanted for uttering death threats and other breaches, your ticket to Ottawa awaits.