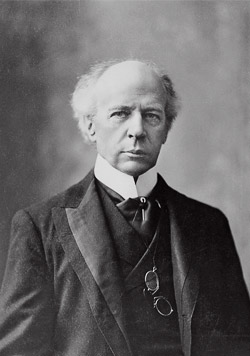

How Laurier’s stirring speech defending Riel forged his reputation

An exclusive excerpt from André Pratte’s biography of Wilfrid Laurier

Share

“Those who are seeking a knight in shining armour, a defender of principles against all odds, will be disappointed by Wilfrid Laurier,” writes André Pratte in his biography of Canada’s seventh prime minister, the latest in Penguin’s Extraordinary Canadians series (in stores March 8). “Those who know that a man of principle can govern only by showing patience and realism will find in him a model.”

He was a master of rationality, reason and the middle ground—“the most pragmatic of men,” as Pratte dubs him. And not only was he able to sustain such balance—serving in Parliament from 1874 to 1917, as prime minister for 15 of those years—but he did so passionately and at a time when the young nation was divided by questions of language, race, religion, region, war, imperialism and nationalism. “What I discovered for myself was how much he reflected what Canada is or in some cases should be,” says Pratte, the editor-in-chief of La Presse. “Canada is built on compromise and conciliation and dialogue and listening to others and trying to find common ground, and Laurier not only did that because it was imposed on him by the country’s situation, he really was someone who wanted to discuss and wanted to look for compromise.”

And if many of the same issues persist, it is a shame not only that we so rarely hearken back to Laurier’s words but also, as Pratte concludes, that no one has quite filled the void he left.

EXCLUSIVE EXCERPT

The subject of Laurier’s first English speech in the Commons was extremely sensitive: whether Parliament should expel the rebel Louis Riel, who had just been elected to the House. A few years earlier, the rebellion of the Red River Metis in Manitoba had aroused strong emotions. For the first time since Confederation, francophones and anglophones were diametrically opposed. The English-speaking wanted the head of the man whose “provisional government” had shot one of their own, the Orangeman Thomas Scott, during the uprising; they conveniently forgot the abuses committed against the Metis by English settlers in the North-West. The French Canadians spontaneously sympathized with Riel, a francophone; they closed their eyes to the arbitrary justice of which Scott had been the victim.

Tensions in the Commons were very high. But while the majority of the members gave in to their emotions, Laurier made a stirring appeal to reason and justice. As a French Canadian, he could have responded to the Riel affair by taking the easy path of following cultural prejudices. Instead, he chose to be guided by universal principles. This would continue to be a feature of his original, moderate yet bold approach to relations between the two principal nations that make up Canada.

Two amendments were proposed to the motion to expel Riel. The first one, which declared an amnesty for him, was the one clearly favoured by the francophones. Laurier spoke in defence of the other amendment, which stated that no decision would be made until a Commons committee had studied the matter. This, too, was typical of Laurier: rather than taking a firm position on a question, he generally tried to play for time. The elevated tone of his speeches gave the impression that he was taking a strong position, but the elegance of his words often camouflaged great circumspection. What his adversaries criticized as weakness would be his most formidable tactical weapon. Many years later, in a book on his famous friend, Laurent-Olivier David wrote: “His nature and his character led him to rely, perhaps sometimes too much, on time and the unexpected to resolve difficulties, to put off taking decisive action, to play the patient role of Fabius, but he claimed that temporizing had served him very well.” In short, Laurier used time as all great political and military strategists do.

At the beginning of this speech on the fate of Riel, Laurier established his position in a surprising way: “I wish to declare at the outset that I have no preconceived opinion on the question before us. I have no bias against the member from Provencher [Riel] individually, nor do I have a predisposition in his favour.” Few Canadians, anglophone or francophone, could have shown such objectivity, or would have dared to. Laurier came to Riel’s defence, not because the Metis leader was French-speaking and was fighting for the rights of his people against the English Canadians, but because his basic rights, his rights as a British subject, were being flouted. In this matter, Laurier maintained, the House was acting somewhat as a court. Riel had never been formally charged with Scott’s murder. On the contrary, the federal government had considered him the leader of a legitimate authority, with whom Ottawa had negotiated the creation of the new province of Manitoba and the transfer of land to the Metis. As part of the negotiations, Riel had even been promised that there would be no charges against him for acts committed during the uprising. How could Parliament now treat him like a fugitive from justice?

And what did Laurier say to his French Canadian compatriots who supported the Metis leader unconditionally? Was he not in favour of amnesty? Of course. However, he felt that the strategy of the francophone members of Parliament was wrong and that the demand that the House decree an immediate amnesty would certainly be defeated. This practical sense of politics, which Laurier showed throughout his career, did not prevent him from defending Riel with conviction: “It has been said that Mr. Riel was only a rebel. How is it possible to use such language? What act of rebellion did he commit? Did he ever raise any other standard than the national flag? Did he ever proclaim any other authority than the sovereign authority of the Queen? No, never. His whole crime and the crime of his friends was that they wanted to be treated like British subjects and not bartered away like common cattle. If that be an act of rebellion, where is the one amongst us who if he had happened to have been with them would not have been rebels as they were? Taken all in all, I would regard the events at Red River in 1869–70 as constituting a glorious page in our history, if unfortunately they had not been stained with the blood of Thomas Scott. But such is the state of human nature and of all that is human: good and evil are constantly intermingled; the most glorious cause is not free from impurity and the vilest may have its noble side.”

Over the years, Laurier often used this strategy: defending a cause dear to the French speakers of the country, he would try to win over the other “race” by appealing to principles that were dear to them, such as fair play and the rule of law. He wanted every cause to be judged on its merits, and not on the basis of language, religion, or ethnicity. Quite a demand! But isn’t this the only attitude that is appropriate in an authentic democracy, in a society governed by the rule of law? Isn’t it still the only one possible today, in a country as big and diverse as ours?

While he urged anglophones to remain faithful to the ideals of their mother country, Laurier asked francophones to understand that as a federal politician, he had to take into account the interests of everyone in the country. “I ask you one thing,” he would say to Quebecers in his first public address as leader of the Liberal party in 1887, “that, while remembering that I, a French Canadian, have been elected leader of the Liberal Party of Canada, you will not lose sight of the fact that the limits of our common country are not confined to the province of Quebec, but that they extend to all the territory of Canada, and that our country is wherever the British flag waves in America. I ask you to remember this in order to remind you that your duty is simply and above all to be Canadians.”

The new member of Parliament impressed his colleagues and journalists from English Canada with his speech on Riel. The Montreal Herald commented: “Mr. Laurier made a magnificent speech in support of Mr. Holton’s amendment. It may be the best of the whole debate—calm, logical and thoughtful. He has made his mark and placed himself in the front rank of our debaters.” However, Laurier was not able to convince the majority of members of Parliament, and Riel was expelled from the House. The following year, the Mackenzie government offered Riel amnesty on condition that he leave the country for five years. Laurier supported this even though the people of Quebec would have preferred a full amnesty. In his view, a conditional amnesty was simply the best compromise possible.

Compromise is the key to Laurier’s entire career as a public figure. Like most great Canadian leaders, he was a conciliator. It is this art of finding a middle course that would enable Laurier to govern the country so successfully for so many years. It is this art, too, that would earn him the enmity of radicals of every persuasion. To those who are blinded by an ideology, any compromise is a capitulation to evil. To those who fear the disappearance of their culture, it is the first step toward decline and extinction. Both the former and the latter see anyone who makes compromises as a weakling, an opportunist, or a traitor.

Dictionaries generally give two meanings for the word compromise: “a settlement of differences by mutual concessions” and “an act prejudicial to one’s conscience.” The two are not the same. A just compromise is one by which a person reaches an agreement with both his or her conscience and another party. In Latin, compromissum means “mutual agreement.” Compromise is essential for individuals and countries.

Without compromise, there is no marriage, no social life, no federalism—and no Canada. And those people, past and present, who have sought and worked out compromises should be seen not as weak, much less as traitors, but as the builders of our country.