A toxic drug, more powerful than fentanyl, hits Alberta

How an Alberta professor’s good research was used to create an ultra-toxic drug, decades after he shelved it

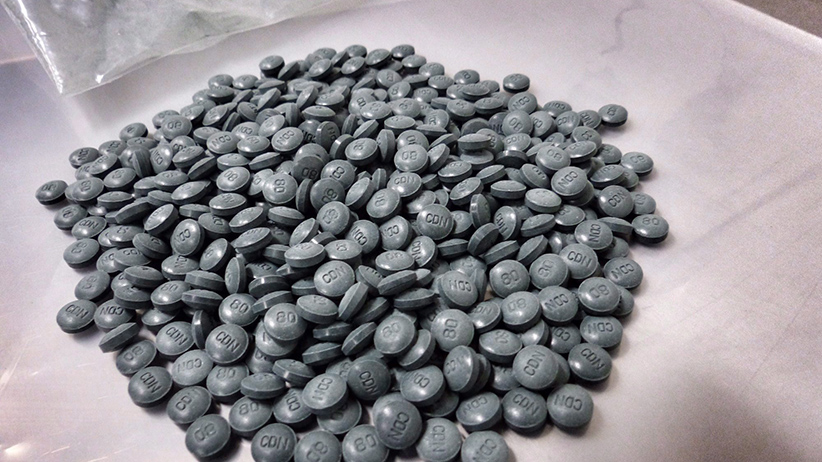

Fentanyl pills are shown in a handout photo. Police say organized crime groups have been sending a potentially deadly drug through British Columbia to Alberta and Saskatchewan using hidden compartments in vehicles. (Alberta Law Enforcement Response Teams/CP)

Share

Calgary police never really wanted the answer to the question: what can possibly be more deadly than fentanyl? After all, the drug had emerged from virtual obscurity to become Alberta’s worst killer, snuffing out 272 lives in the province last year, and more Calgarians than homicide and traffic fatalities put together.

Officers first found their answer in a household safe in Calgary’s rural outskirts last August. Inside was a familiar sight: 110 green pills, likely fentanyl, known on the streets as shady eighties or green beans. A random sample of 20 pills went for analysis to a lab in Burnaby, B.C. A week before Christmas, Health Canada’s results opened a new frontier in Alberta’s drug war: three pills instead contained W-18, an opiate authorities knew little about. But what they did know was unsettling. While fentanyl is roughly 100 times more powerful than morphine, W-18 is about 100 times more powerful than fentanyl. It has zero clinical use, has only been tested on mice, and isn’t yet classed as a controlled substance in Canada or the United States. And it’s unclear that naloxone, the agent used to reverse fentanyl overdoses, would work against its obscure synthetic cousin. “Which is obviously challenging, and very scary,” says Staff Sgt. Martin Schiavetta of the Calgary Police Service’s drug unit.

These scraps of intelligence hail from 33 years ago, and from a few hours north in Edmonton. There, at the University of Alberta, pharmacology professor Ed Knaus and colleagues were experimenting with chemical compounds. “We were really looking to make a non-addictive analgesic or painkiller; that was kind of our goal,” recalls Knaus. They applied in 1982 for a patent for their 32 W-series compounds, all of varying potencies; the 18th compound was by far the strongest. But Knaus and his researchers realized these acted as opiates, so would be addictive. Drug companies never picked up the patent, and it lapsed by 1992, just another of the many research ventures realized or unrealized in Knaus’s 37-year professorial career.

Knaus, now in his seventh year of retirement, says he recently got an unexpected call from the RCMP in British Columbia about his long-abandoned work. “It doesn’t make me feel good that people have picked this up,” he says.

As is common with drug trends, those first three pills were just the beginning. In April, police announced the seizure of four kilograms of W-18 powder in Edmonton, and put emergency rooms on alert. “To put in perspective, this is enough to kill every man, woman and child in Alberta about 45 times over,” tweeted Dr. Hakique Virani, a public health physician in Edmonton.

It’s a dark coincidence that a compound devised by good quality research in Edmonton landed, three decades later, in a suspected drug trafficker’s safe near Calgary. The delta for this story, as with so many synthetic drug stories, is believed to be somewhere in China. It’s where illicit drug manufacturers have been plundering pharmacological history in search of the most exotic and cheapest ways to trigger euphoria in the brain.

“That’s what the Chinese chemists are doing: they’re going through these old journals and are digging up these old compounds they know will bind to certain receptors, and they look for ones that are extremely potent,” says Brian Escamilla, a forensic chemist at a California firm that trains police to safely handle drugs and clandestine labs. His lecture at a Vancouver conference last spring was the first time Schiavetta, the Calgary officer, heard of W-18.

The August seizure and December lab results marked the first publicized discovery of W-18 in North America. Since then, Western Canadian labs and police have been put on alert, New Jersey police have queried Schiavetta, Kentucky legislators have mused about a crackdown, and every high school student in Edmonton is getting warned about this synthetic drug that may or may not have begun to trickle onto Alberta streets.

It’s become part of an Edmonton Police Service slide presentation about fentanyl, the motif of which is morgue toe-tags. After a litany of grave warnings about fentanyl, and warning a small dose could kill after two minutes, constables warn teens of the emerging drug that’s much, much worse, only known by a letter and number. “We couldn’t even tell you how many minutes or seconds you have to live with it,” Const. Cherie Jerebic says about W-18 in her presentation.

At least fentanyl is a menace authorities understand. It’s long been used as an anesthetic, and doctors distribute fentanyl patches as strong, three-day painkillers. When it began its spread in Canada three years ago, dealers sold it as fake OxyContin, a much less powerful narcotic, but for the last year, Calgary drug addicts and casual users have sought it by name, Schiavetta says. At $20 a tablet, the officer says organized crime groups are moving away from traditional drugs like cocaine and into fentanyl because it’s easily ordered online. “We’ll never arrest our way out of the fentanyl problem. It’s made for pennies in a foreign country,” Schiavetta says.

Calgary police have seized tablets with 4.6 to 5.6 milligrams of fentanyl (they warn a dose of two milligrams, equal to a few grains of salt, can kill the average person). This makes the prospect of pills with mere traces of W-18, vastly more potent at hitting the brain’s opioid receptors, utterly chilling.

On the drug-focused message board BlueLight.org, W-18 has been discussed since 2012. “When a drop of liquid from an entire pool has the potential to paralyze your lungs, it’s a pretty good idea to stay the f–k away,” one forum moderator said this month. “That is chemical-warfare-level potency.” Even opening a bag and inhaling some could kill, another user said.

Alberta hospitals have been on the lookout for W-18 since January, but with limited results. “W-18 is not yet detectable in human specimens (blood or urine), given the very low concentrations that appear in bodily fluids,” Mark Yarema, medical director of Alberta’s Poison and Drug Information Service, told Maclean’s in an email. Post-mortem exams may turn up heroin or fentanyl, but those findings may mask minuscule amounts of W-18. “It’s such a tricky animal that I have a feeling we’re probably missing a few cases of overdose deaths,” Escamilla says.

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency confirmed to Maclean’s it has seized W-18 in drug investigations, but would not say when or where. The DEA can use emergency powers to put drugs with no known medical use on its controlled substances list, but neither that agency nor Health Canada has yet to make this drug illegal. Health Canada declined to make somebody available for an interview, largely because so little is known about W-18, a spokesman says.

Cayman Chemical, a Michigan firm that manufactures illicit drug specimens as testing standards strictly for research and forensic labs, first produced W-18 about a year ago, marketing vice-president Brian Conkle says. In recent years, designer drug cooks are getting so far ahead of the medical establishment with creative drug analogues and obscure compounds, that Cayman has made a flipbook for authorities trying to identify the molecular head, body and tail of a synthetic cannabinoid they’ve encountered. The company is mulling doing the same for other drug variants. “There’s no way to stay ahead of it. It’s just a tragedy,” he says.

While Schiavetta says Calgary police don’t feel like they’ve yet turned the corner on fentanyl, Alberta has followed British Columbia and now distributes take-home kits of naloxone, which can counteract fentanyl overdoses. It’s a medicine that works to counter various opiates, but in Knaus’s 32 W compounds, he only tested naloxone’s effect in W-3. A fact sheet by the B.C. Centre for Disease Control notes that reversal has never been tested in humans, but naloxone should theoretically be effective against W-18, but perhaps in high doses.

Knaus, the inventor who just wanted to create a miracle painkiller, says authorities must test more, but he can’t see why the typical overdose antidote can’t work. “It’s disturbing to me, it is a concern, but it isn’t like they don’t have something that they do immediately. They can use naloxone,” Knaus says.

That is, if it’s used in time, and in adequate dosage. On the first weekend in February, Schiavetta says paramedics reversed one suspected fentanyl overdose, but found two other Calgarians dead. If W-18 is added to this already deadly scene? “It could have devastating effects,” Schiavetta says. “But we’re not there yet.”