A (very) long-term investment in VenGrowth

How a once promising mutual fund turned into a money-losing trap

Share

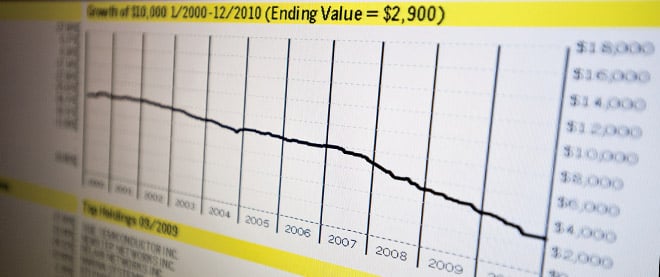

When it comes to mutual funds, Audrey Sauder of Waterloo, Ont., has seen her share of dogs over the years. But few brought as much grief for the financial planner and her clients as those run by VenGrowth Asset Management Inc. Every one of VenGrowth’s funds have lost money over their lifetime, with at least one down a gut-wrenching 40 per cent over the past 12 months.

Had they been ordinary funds, Sauder might have simply told her clients to take what’s left of their money and run. Toronto-based VenGrowth, however, operates in a special category known as labour-sponsored investment funds, or LSIFs, which are a different beast. Envisioned as a way to raise venture capital, LSIFs typically invest in small, privately held technology companies in the hopes of one day hitting it big (BlackBerry-maker Research In Motion Ltd. was once a recipient of LSIF money). Of course, picking winners and waiting for them to develop takes time, which is why investors must agree to investment terms of eight years, and are compensated for doing so with lucrative tax breaks.

It’s an inherently risky business. And while VenGrowth’s 135,000 investors should have known what they were getting into, few likely imagined they would find themselves trapped in their volatile investments indefinitely. But that’s exactly what happened after a decision to halt redemptions in two of VenGrowth’s five funds following the 2008 market crash (redemptions on a third fund were halted in 2009). “It was ridiculous,” says Sauder, who also happens to be a VenGrowth investor. “We had already spent eight years waiting to cash this thing out.”

A light finally appeared at the end of the tunnel last fall. VenGrowth announced a merger deal with a rival fund company. But instead of providing suffering investors with a path to freedom, it ended up raising questions about the motivations of VenGrowth’s managers, who stood to gain millions in termination fees upon closing the sale. Although the deal was eventually approved by a majority of unit holders, it has since foundered on disclosure concerns raised by regulators, prompting more investor frustration and a fresh round of finger pointing.

The unfortunate saga threatens to cast an even darker cloud over the troubled LSIF industry. Once a popular choice for Canadians’ registered retirement savings plans, LSIFs have fallen out of favour in recent years as investors flee their dismal performance and high management fees (more than double that of normal mutual funds), and critics fret about the impact of tax breaks on dwindling government coffers. Ottawa offers a 15 per cent tax credit, which is often matched by the provinces.

The original idea behind the fund class was to spread the considerable risk of venture capital investing among a diverse group. The approach was championed by labour unions that wanted to see more money invested in their communities, creating new jobs—hence the “labour-sponsored” aspect of the funds. Governments, meanwhile, viewed LSIFs as a way to encourage innovation, boost the economy and support small businesses.

Canadians responded by pouring their money into LSIFs during the tech boom in the late 1990s, so much so that some expressed concern that LSIFs would crowd out traditional venture capital firms. And VenGrowth, founded in 1982 by Earl Storie, quickly emerged as one of the pre-eminent players in the sector, boasting more than $1 billion in assets under management. Storie is still listed as a VenGrowth managing general partner alongside Mike Cohen, David Ferguson and Allen Lupyrypa.

Fortunes changed drastically after the bubble burst in 2000. Like other LSIFs, VenGrowth suddenly found itself saddled with a bunch of private companies that were difficult, if not impossible, to sell at a profit. The outlook worsened further in 2005 when the Ontario government decided to phase out its LSIF tax credits, beginning in the 2010 tax year. The decision staunched the flow of new money into many LSIFs and made funding redemptions even more difficult. The 2008 stock market crash was the final straw, ultimately forcing VenGrowth to suspend redemptions for some unit holders and move instead to annual distributions of any excess cash. But just because unit holders were essentially trapped didn’t mean they were free from paying the fund’s hefty management fees.

So after two years of forking over money for the privilege of being stuck even longer in a bad investment, VenGrowth investors welcomed the news on Oct. 12 that rival Covington Capital would purchase the five troubled VenGrowth retail funds. With combined assets of $368 million, the VenGrowth funds were to be merged into one of Covington’s, creating a larger and more diversified fund that promised improved liquidity.

Still, it was far from a perfect solution. Many investors would have still faced a 40 per cent penalty if they tried to redeem immediately. And, after parsing the dense information circulars, many were upset that VenGrowth’s managers stood to rake in roughly $20 million in termination fees—money that would come out of the same funds that investors had been unable to exit because of a lack of cash. “I spent the weekend trying to read that thing,” says Sauder of the documents mailed out to unit holders. “The fees that they were giving themselves were insane.”

Sensing rising frustration, Vancouver-based GrowthWorks, another rival fund, entered the fray. GrowthWorks waged a proxy fight by offering investors a similar deal that proposed lower redemption penalties and payment of $5 million of the $20 million in management termination fees. David Levi, the CEO of GrowthWorks, told Maclean’s that GrowthWorks is an ideal candidate to manage the VenGrowth funds since it holds stakes in many of the same assets, which he argues are potentially valuable in the right market. In the meantime, he says GrowthWorks has “tried very hard—particularly in Ontario—to focus all of our attention on finding liquidity so we could return money to investors.” VenGrowth’s unit holders ultimately voted in favour of a reworked Covington deal, but critics claimed the vote was skewed by tight deadlines, busy fax machines and last-minute changes to procedure—all charges that VenGrowth denies.

It was a short-lived victory at any rate. In the weeks before Christmas, a fairness hearing on the proposed deal in an Ontario court unearthed new revelations—namely a proposed consulting contract between Covington and a numbered company owned by four VenGrowth fund directors and management principals. Although the information circular mentioned the existence of the contract, it wasn’t until an actual copy of the document was filed with the court that investors learned who would actually be doing the consulting. “As it turns out, the VenGrowth portfolio managers weren’t really being ‘terminated’ at all,” wrote Al Kellett, a Morningstar fund analyst, in a recent report. He estimated that the VenGrowth managers stood to earn roughly $5 million per year for doing an estimated five hours of work per month. “That is a consulting fee of $85,000 an hour, which sounds like nice work if you can get it.”

VenGrowth denies there was any intent to deceive investors. John Kingston, a spokesperson for VenGrowth and a member of the special committee charged with performing a strategic review of the fund company’s options, says termination fees are common when businesses change hands, as are consulting contracts designed to help buyers manage their newly acquired assets. Besides, he says, the consulting fees were to be paid by Covington, not the fund, and would likely be significantly less than $5 million. But why weren’t they fully disclosed? According to Kingston, VenGrowth’s managing partners had no reason to believe it was necessary until the Ontario Securities Commission said so “at the 11th hour.” As a result, he says, VenGrowth didn’t have time to mail out amended information circulars before the deal’s Dec. 31 deadline. “In my personal opinion, I’m not sure it would have had a bearing on the shareholder vote,” says Kingston, adding that VenGrowth has since received five “expressions of interest” from potential buyers, two of which are Covington and GrowthWorks.

Others say the deal was doomed from the beginning. “From day one, the process was terrible and the transparency was awful,” says Dan Hallett, the director of asset management at HighView Financial Group. He says it’s easy to understand why some beleaguered investors felt like VenGrowth’s managers weren’t always looking out for their interests. “Based on the shareholders I’ve talked to, they sure think it was done deliberately.”

Whatever the case, one thing is clear: the resulting mess has done little to win back investors to the flagging sector, which just six years ago accounted for more than a third of all venture capital money in Ontario. Recent industry figures compiled by the Canadian Venture Capital and Private Equity Association show that, while Canadian venture capital deals increased in 2010 for the first time in three years, rising 10 per cent to $1.1 billion, the industry is still having a tough time raising money. New commitments of capital last year fell 24 per cent to just $819 million, the lowest in 16 years. With LSIFs in decline, Hallett says it’s not clear where new sources of venture capital are going to come from.

Back in Waterloo, Sauder says VenGrowth has clearly been a disappointing investment. “I think the thing should be completely shut down,” she says. “Sell the underlying investments and give the people their money back.” Given recent history, however, investors would be wise not to hold their breath.