An ugly homicide number we need to discuss

Aboriginal people account for a disproportionate share of homicide victims and accused murderers, a reality Canada must confront in order to halt the violence

Participants take part in a rally on Parliament Hill in Ottawa on Friday, October 4, 2013 by the Native Women’s Assoiciation of Canada honouring the lives of missing and murdered Aboriginal women and girls. The RCMP says it has completed a comprehensive file review of murdered and missing aboriginal women and girls within Mountie jurisdiction – more than 400 in all – and will continue to pursue outstanding cases. Newly disclosed briefing notes say the national police force has reviewed 327 homicide files and 90 missing-persons cases involving aboriginal females. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Fred Chartrand

Share

This is what it means to be born Indigenous, in Canada, in the 21st century: You are twice as likely to die in infancy. You will be nine times more likely to be sexually assaulted as a child and three times more likely to drop out from school. You will be twice as likely to lose your job. If you have a job, you will earn 60 per cent less.

For Métis, Inuit, and First Nations Canadians, the deck is stacked against you from birth, and the stakes are as high as they can get. For many Indigenous people, who face an incarceration rate 10 times the national average, a losing hand means prison. For more than a thousand missing or murdered Aboriginal women, the rigged game ended in death. These numbers aren’t secret. I’ve written about them a dozen times before, and we’ve been hearing them repeated by politicians, elders, academics and activists for decades now.

But here is a new number, from data released Wednesday by StatsCan: While Indigenous Canadians are six times more likely to be the victim of murder, they are eight times more likely to be a murderer.

Last year RCMP Commissioner Bob Paulson told First Nations leaders that Indigenous perpetrators were responsible for 70 per cent of the solved homicides of Aboriginal women. They responded with furious indignation, and Paulson was attacked for vilifying the Indigenous community. NDP MP Niki Ashton, among many others, dismissed the RCMP numbers and demanded to see the data.

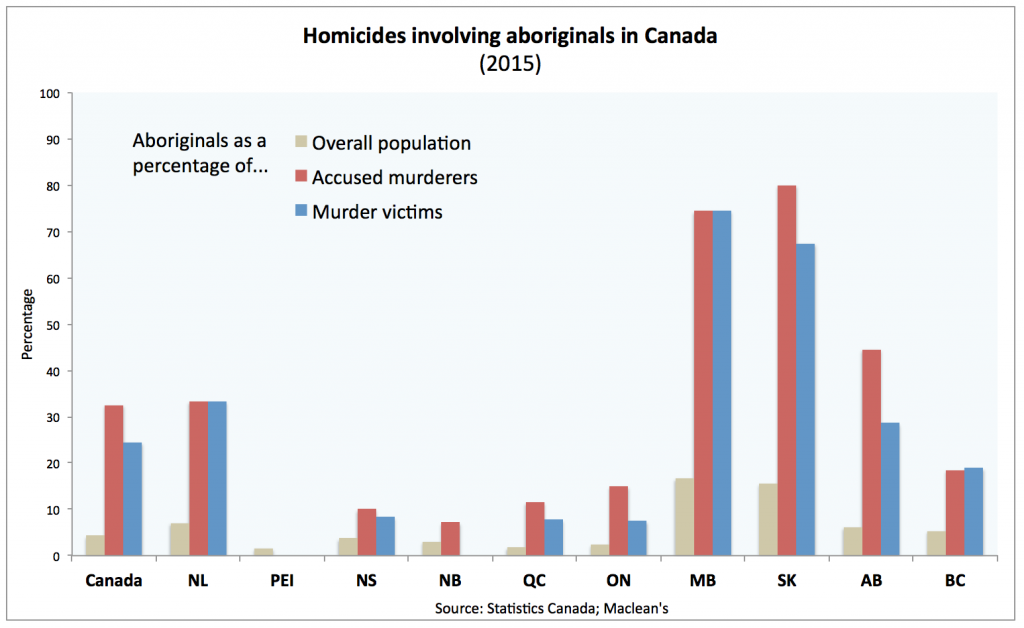

Well, StatsCan began to collect that data and now we have the latest figures. They’re ugly. The Indigenous community makes up less than five per cent of the population in Canada, but accounts for 32 per cent of all suspects accused of murder. In Manitoba and Saskatchewan, it’s an astounding 74 per cent and 80 per cent, respectively. (The relative percentages for murders committed by Aboriginal women are even higher, but come from much smaller absolute numbers.)

And this presents two questions: Why are Indigenous Canadians so much more likely to commit murder? And why should we be talking about it?

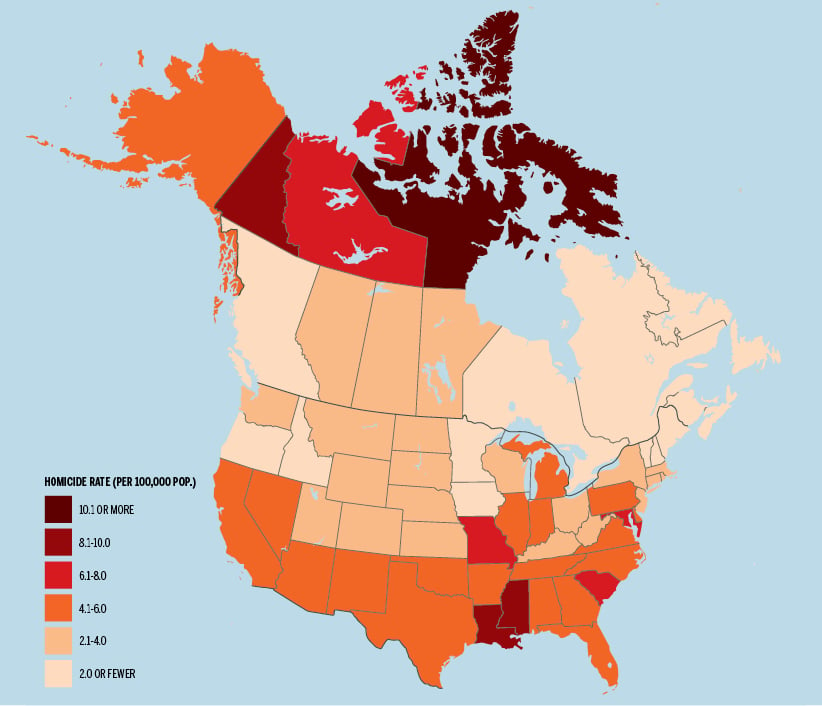

The first question is much easier to answer. This is an issue of “place”, not “race.” Consider this map of Canada and the United States, based on research compiled here.

It is not a coincidence that the Canadian north is far more violent than any other province or state in either Canada or the U.S. When you drill down into the regional numbers for provinces like Saskatchewan, or look at the different neighbourhoods in Winnipeg, you see a similar picture on a smaller scale. Disconnected, unhealthy, and poor communities have far higher rates of violence. And these are adjectives that all too often describe the northern villages, remote reserves, and inner city neighbourhoods where Canada’s Indigenous population lives.

In these communities historic abuses, a lack of infrastructure, and social dislocation have exacerbated several factors that criminologists have long associated with higher rate of violence: large numbers of youth, single-parent households, high unemployment, and alcoholism.

The population in Canada’s Aboriginal communities is much younger than almost any other demographic, with a mean age of 27 years versus 40 for the rest of the country. More young men means more angry young men. And the places these kids are growing up in are more likely to be poor, and have higher numbers of single-parent homes.

These households are also the scene of far more domestic abuse compared to the Canadian average. Even when you control for social variables (such as rates of alcoholism or unemployment), “Aboriginal women consistently report a rate of partner violence much higher than their non-Aboriginal counterparts,” according to the Canadian Department of Justice.

This has created a vicious cycle in these Indigenous communities. Children raised in violent homes are up to 17 times more likely to have serious emotional and behavioural problems. Is it any wonder that an Aboriginal child, raised in a poor, single parent home, witnessing domestic violence, exposed to alcoholism, and warehoused in a sub-par school system, ends up becoming extremely violent themselves?

Which brings us to the second question, why is it important to confront the fact that Indigenous men are much more likely to be violent than other demographics? Because Commissioner Paulson was right. The overwhelming majority (71 per cent) of Indigenous homicide victims knew their attackers. They were killed by members of their own community, family members or friends.

And, shouting that the RCMP must “Do more!” will do nothing. You don’t end domestic violence with more police patrols. This is a much more complex problem, that needs the interventions by communities, elders, and provincial and federal agencies.

Why do Indigenous Canadians have the highest rates of victimization in the country? Because, as this latest data emphasizes, they live in the most violent communities in the country. The fact that I have to point this out, and that doing so will be met with anger, shows the embarrassingly primitive state of our national discussion on this issue. If we are ever going to address this crisis, we need to focus on where it starts: in the very communities First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Canadians live.