Buried alive: An avalanche survivor breaks his silence

From 2015: A survivor shares what really happened on the mountain during the 2003 Alberta avalanche, in which seven schoolkids died.

PREMIUM — A helicopter flies over Rogers Pass in Glacier National Park Sunday, Feb. 2, 2003. Seven students from Strathcona-Tweedsmuir School in Alberta were killed on Saturday Feb. 1 when they were struck by a avalanche. Jonathan Hayward/CP

Share

The first part of this story may be familiar, especially to those in Western Canada. It starts with a group of backcountry skiers venturing into British Columbia’s Glacier National Park in early 2003, and ends with one of the deadliest avalanches in Canadian history. Seven people lost their lives to the slide. Adding to the horror, the victims were schoolkids.

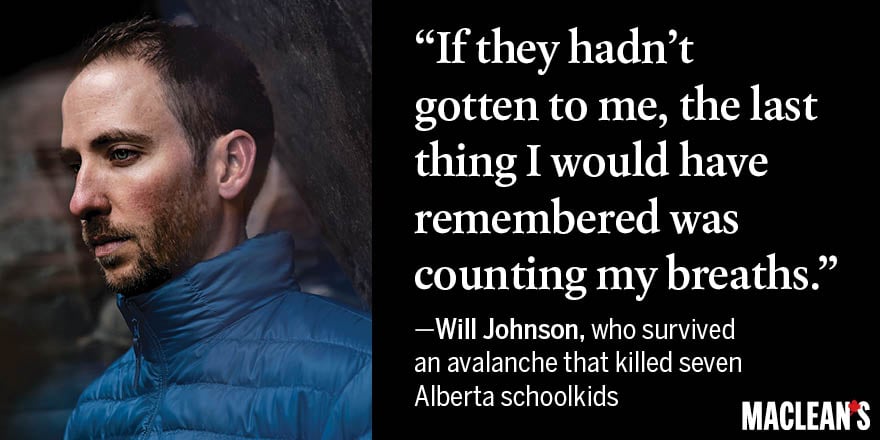

Media coverage focused primarily on the deaths of the seven students. Journalists interviewed grieving parents, school officials and rescuers, trying to make sense of an incomprehensible tragedy. But many questions remained unanswered, because those who made their way off the mountain refused to speak publicly about what happened that frozen day in February. Their names were never released and, to this day, the survivors and people who know them continue to fiercely protect their collective anonymity. But in 2015 (12 years after the tragedy), Will Johnson, one of the kids who walked away that day, is ready to break the silence.

The 28-year-old slips into the booth at a pub in Calgary’s Marda Loop. He orders coffee, black, explaining that he spent the previous night in the emergency room, waiting for his roommate to get his forehead stitched up after some roughhousing got a little out of hand. Despite the lack of sleep, Johnson is bright-eyed, friendly and articulate. You’d never guess that behind the easy smiles and laid-back persona hides a painful past.

IT WAS AROUND 6 a.m. on Friday, Jan. 31, 2003, when 15-year-old Johnson joined his 13 classmates in the Canadian Tire parking lot on Richmond Road in Calgary. The weather was unseasonably warm as they loaded their gear into the back of the white charter bus while parents chatted beside idling vehicles. The air buzzed with anticipation for the adventure ahead, a four-day backcountry skiing expedition into B.C.’s Interior.

Many students and families are drawn to Strathcona-Tweedsmuir School (STS)—a prestigious private school located about half an hour south of Calgary in Okotoks, Alta.—because of opportunities like this one. The overnight to Glacier National Park was a rite of passage for STS students, something they’d trained for since the start of the school year. Johnson wasn’t supposed to be there. He played badminton at the national level and had missed his scheduled excursion for a tournament. But because his teachers didn’t want him to miss out on the experience, he was permitted to tag along with another class. He’d known some of the students on this trip since elementary school. There were 80 or so 10th-graders enrolled at STS that year. “It was a really close-knit group,” says Johnson.

After five tedious hours winding west along the Trans-Canada Highway, the bus pulled up in front of the Rogers Pass Discovery Centre, halfway between the B.C. towns of Golden and Revelstoke. Rogers Pass is considered one of the safer backcountry locations to explore, but it’s certainly not immune to danger. Only 12 days earlier, an avalanche in a nearby range had killed seven experienced skiers. But the school had facilitated dozens of trips to Rogers Pass, without incident, since 1990. STS teacher and group leader, Andrew Nicholson, better known as Mr. Nick, had overseen several of them himself.

The excursion fit nicely into the Alberta curriculum, which said that students were to examine the “consequences of their actions [in] relationship with the environment,” and to “assess physical hazards imposed by particular terrain and conditions (e.g., avalanche, lake and river ice, and bush travel).” Mr. Nick had a spotless record. If he found any reason to doubt the safety of Rogers Pass in the coming days, the group would ski at Kicking Horse resort instead—no questions asked.

Mr. Nick hopped off the bus, spoke briefly with officials and picked up a Parks Canada bulletin that evaluated local snow conditions. It ranked the avalanche risk in the area as “moderate” (two out of five) below the treeline, versus “considerable” (three out of five) in the upper alpine sections—where they had no intention of going. It also noted that unseasonable rainfall back in November had created a layer of granular ice crystals sandwiched between loosely packed snow that was failing compression tests throughout Glacier National Park.

Bulletin in hand, the group unloaded the bus and skied the final leg of the day’s journey. Along the trails carved out between snow-swept hemlock trees, Mr. Nick guided the students through avalanche-assessment exercises. They dug pits and tested the snowpack and excavated caves for shelter. They buried their beacons and practised using transceivers to pick up the signal; the deeper the snow, the weaker the pulse.

Before the sun set around 5:30 p.m., they arrived at the Arthur O. Wheeler Hut, a picturesque three-room log cabin owned by the Alpine Club of Canada. The students got to work hauling firewood and prepping food for dinner. After helping a classmate finish off 2½ pounds of Hamburger Helper (“I remember saying, ‘Dude, that’s disgusting. Why did you make so much?’ ” Johnson says, laughing), it was time to plan for the next morning. “Our teachers walked us through the steps,” says Johnson. “We had two routes to discuss. The snow conditions were fairly similar in both routes, but the one that we ended up choosing had more manageable slide paths.”

Bedtime was filled with “kid jokes about who farted in their sleeping bag” and giggling and snoring. “There are 17 of us sleeping in this room, giving each other a hard time,” Johnson recalls. Despite the tittering that lasted long into the night, it was the last peaceful sleep he would experience for more than a decade.

The sky was grey and the temperature hovered around zero degrees when the group got its start at 9:30 the following morning. It was a perfect day to challenge the rugged terrain. The plan was to ski to Balu Pass, moving parallel to the silver ribbon of water tracing the bottom of Connaught Creek Valley. They would stay on the eastern side of the creek. The western side of the valley was steeper and starker, leading up to the summit of Mount Cheops. Barring delays, they would reach their destination in under three hours.

Read more Maclean’s long reads:

The inheritance wars

The incredible true story behind the Toronto tunnel

How your brain can heal itself

In remote areas like this, there are no chairlifts, and skiers are on their own when it comes to moving uphill. Simpler ascents can be done on skis; other sections require hiking. The STS group planned to slowly gain altitude for the first half of the trip, allowing for a long, luxurious descent on the way back. It was hard work and, at about the halfway point, they stopped to refuel. While they munched on sandwiches and trail mix, a pair of seasoned skiers came through the trees and offered a quick greeting before pressing on. “They were heading in the same direction we were, but they were kicking our ass for time,” Johnson remembers.

At 11:45 a.m., the STS group paused at the edge of the forest and prepared to cross their second major slide path. They looked out at where runoff from multiple peaks would collect come the spring thaw. Across the valley, on the far side of the creek, the summit of Mount Cheops was hidden behind low, ashen clouds moving slowly along the ridgeline. As their training had taught them, the students minimized risk by partnering off and staggering their starts, creating 50-foot gaps between each pair of skiers. With two adults bringing up the rear, the students followed Mr. Nick out onto the slide path.

Out in the open, Johnson had a better sense of the sprawling landscape that surrounded them. The grey mountain ranges stretched on for hundreds of kilometres in every direction. Standing in the middle of it felt like being on another planet. There wasn’t a breath of wind; the air was cool and silent except for the murmur of skis atop virgin snow. “It was warm enough that I didn’t have my hat on. My jacket was wide open. I think I was maybe third or fourth back from the front,” Johnson recalls. “Then someone yelled.”

That Saturday was a day off for Abby Watkins and Rich Marshall, and the certified backcountry guides had planned to spend a couple of easy hours on the popular trails near the highway. As they passed a large group of teenagers, Marshall noted that the students were equipped with appropriate gear, including 240-cm carbon probes, collapsible shovels and transceivers, and seemed at ease in the environment. They said hello, shared a few words with Mr. Nick, and continued on their way, gradually climbing as they, too, pushed north toward Balu Pass. An hour later, they stopped to sip tea from a thermos and to take in the scenery. They spotted the school group emerging from the trees into a clearing 300 feet below them, a procession of shadows floating across a snow-white sheet. It was one of those rare moments that become a Polaroid in the scrapbook of your memory. But the vignette was shattered by a sound they recognized instantly.

There was no precursor. No earthly tremble. No human trigger. Only a loud crack, followed by a massive avalanche crashing down from the peaks of Mount Cheops. The school group was directly in its path. Marshall tried to warn them, shouting, “Avalanche, avalanche, avalanche!” But his attempt was futile. They could only watch as the snow barrelled down the mountain and back up the far side of the valley toward the unsuspecting group.

Johnson doesn’t remember hearing the crack, but he stopped in his tracks and tried to locate the source of the shouts. Instinctively, he looked uphill, but found the landscape undisturbed. He turned downhill to face Connaught Creek Valley and Mount Cheops on the western side. The clouds initially hid the slide from view, but Johnson watched as an avalanche burst through the coverage and thundered down Mount Cheops’s jagged face. At first, it felt like the slide was far away, and his initial response wasn’t fear, but fascination. “It was surreal,” he says. “But then I saw that our leader had his backpack off, his skis off; he was ditching everything. I don’t know how many seconds we had, but there was no time to do anything. I remember starting to get one ski off. Then there was this wall of powder.”

The avalanche was massive—800 m wide, a kilometre long and five metres at its deepest. On Parks Canada’s five-point size scale, it ranked a 3.5, large enough to topple a building or destroy 10 acres of forest. Five thousand tonnes of snow slammed into the valley bottom before surging up its opposite side. Travelling at 150 km/h, the avalanche swallowed everything—and everyone—in its path.

“The next thing I remember was being in the snow. I was conscious of what it felt like on my body. I remember the sensation of the slide moving up, of it peaking, and then coming back down and settling. In my head, it was, ‘Oh s–t, oh s–t, oh s–t, oh s–t, oh s–t.’ At first, the snow was so fluid, but it settled into concrete. I couldn’t move anything. I couldn’t wiggle my fingers. Which way is up? Which way is down? I couldn’t do anything. I couldn’t see anything. It was completely dark.”

Disoriented and panicking, Johnson realized he’d just been buried alive. Snow was packed so tightly around him that it prevented his chest from expanding: “Every time I breathed [through my nose], my ribs hit a snow wall. My mouth was packed with snow. It was terrifying.” Still, his training taught him that, in a group of 17 people, the odds were good that someone had managed to escape the slide and that a search would soon be under way. Johnson clung to the hope that he would be found. He had no way of knowing that every member of his group was trapped beneath the snow.

Johnson’s body temperature plummeted as blood rushed to his core to protect his vital organs, but he doesn’t remember feeling cold. Hypothermia was the least of his worries; he was running out of air: “I tried to count out breaths. Eight seconds in, eight seconds out. Slow. I knew that eventually, I wasn’t going to be able to breathe anymore. I was going to pass out. I’ve thought a lot about that. If they hadn’t gotten to me, the last thing I would have remembered was counting my breaths.” He’s not sure how long it took to lose consciousness; the time could only be measured in excruciating eight-second intervals.

After watching the group below them disappear, the guides braced for the inevitable impact. Blinded by a powder cloud generated by the force of the avalanche, they waited for the snow to overwhelm them. But it never got there. Watkins and Marshall were alive, topside and the only people in the world who knew that the school group was in trouble.

The threat of a second slide was palpable. But the guides knew that valuable seconds were ticking by. After half an hour, the survival rate of an avalanche victim drops to 50 per cent. At 45 minutes, it’s less than 30. If a person is buried without an air pocket, it’s the same as being underwater. Carefully, Watkins and Marshall skied down to the edge of the run-out zone and spotted a glove sticking out above the snow. The hand belonged to Mr. Nick. Once his face and upper body were cleared, they left him to dig himself out the rest of the way as they moved on to search for beacon signals. Finding the leader first was a stroke of luck; he carried the group’s only satellite phone and immediately called for help, then joined the guides in the desperate search for his students.

Johnson blacked out beneath the snow. It wasn’t painful; he was conscious one minute and gone the next. Just as suddenly, he thundered back into the waking world. He was standing on top of the snow, struggling to zip up his jacket, with no idea how he had gotten there. The memories of that moment come back to him in clipped fragments: “I couldn’t move my hands. I was freezing. Shivering. My hands were shaking. I couldn’t really think. I couldn’t really talk. People had just dug me out. I was out. I was breathing.”

He recognized the skiers from earlier in the day, busy digging nearby. Numb and disoriented, Johnson stared down into the metre-deep hole they’d pulled him from. “I was incredibly lucky where I ended up,” he says. “There was another burial site that they found first, but [that person] was 3½ metres deep. You can’t dig that out with two people, so they marked it [by leaving their probes sticking up in the snow] and moved on. I was the next site.”

When he was finally able to overcome the shock, Johnson and a girl from his class who had been saved minutes after him got to work on the first burial site. They had a single shovel between them, and dug until their lungs burned and their arms felt like cinderblocks. After half an hour, three men emerged from the trees and offered to take over.

By then, Watkins and Marshall had uncovered a fourth person, and several other people were on the scene. Johnson and the girl split up, and he climbed to where another site was being excavated, arriving as an unconscious body was pulled from the snow. The rescuers had to move on quickly, so Johnson and another classmate were tasked with performing CPR. Johnson was reeling from the trauma and exhausted, but, once again, his purpose became singular: “We just focused on compressions and breaths.”

In under an hour, seven helicopters, 48 rescuers and three rescue dogs were on the hill. Johnson continued to perform CPR until paramedics came and asked how long they’d been trying to revive their friend. Again, he wasn’t sure how much time had passed. But it had felt like a long while and the boy’s status hadn’t changed. “They told us to move on, which I think was the first moment that I realized people had died,” Johnson recalls. Dazed, with the dead body of a friend at his feet, he surveyed the destruction. Staring out across the slide, Johnson spotted a vertical probe. Then another. And another. All marking burial sites that were quickly becoming graves.

None of it felt real. “You’re just digging at a stick in the ground,” he says. “You don’t know who’s down there, you don’t know how deep they are, really. You don’t see a body or a face.” Soon, an adult was beside him, telling him it was time to leave. As Johnson realized the truth, the weight of it was crushing: “Anyone who’s not up is not coming up.”

The rescue was spread out across a square kilometre and Johnson desperately scanned for his friends. At that point, he knew of five survivors, himself included. And one victim. But the helicopters had already started taking people off the hill, and it was possible others had made it. Another slide could take out the group, and the rescue crew wanted to evacuate quickly. Johnson was hurried into a chopper and airlifted to Glacier Park Lodge, where he hoped to find the rest of his class. It wasn’t until he reached the hotel and found the others huddled together in a small room that he understood half his friends—seven students—were gone.

As details of the disaster emerged, the news was met with disbelief, anger, devastation and a never-ending list of questions. Why were minors led into what was being called a highly dangerous situation? Why had adults made the decision to take them there? With all the technology available, why had no one predicted the avalanche? A lot of criticism was directed at STS, but the school also received countless letters of support following the tragedy. Ben Albert, Marissa Staddon, Michael Shaw, Alex Pattillo, Scott Broshko, Daniel Arato and Jeffrey Trickett were gone, and a lengthy investigation concluded that their deaths were the result of a horrible accident.

Safely back at home, Johnson struggled to dig himself out. He knew he should feel grateful that he was among the survivors, but he couldn’t come to terms with the outcome. The closest thing to relief came a few weeks after the avalanche, when he and the others returned to STS. The school and the community rallied around them. “It felt good to go back,” he says. “It felt safe.” But, despite the support of friends, family and even strangers, there are parts of Johnson that would never be the same and, for years, he suffered in silence. “I was really good at letting people think I was doing great on the outside, because then nobody asks you questions and no one is hovering around and worrying about you,” he says.

Johnson battled with depression and what he calls “pleasure-seeking for distraction”—a lot of partying and alcohol. Mostly, he drank to forget, but he also drank to fall asleep. The panic attacks are less frequent now, but there were nights when, lying on his back, eyes probing the darkness, he felt the rise and fall of his chest and counted his breaths. For some, the method quiets anxiety and welcomes sleep, but, for Johnson, it took him back under the snow, where he drew what could have been his last breath. Even today, falling asleep feels a lot like dying.

Nearly a decade passed before he finally asked for help. “My dad got me to do an ADHD test, which was sort of his way of introducing me to my therapist,” Johnson says. After that, he checked himself into a month-long day-treatment program in Calgary and took four months off work to “move to B.C., grow a beard, do yoga and just deal with it.” It’s a process that will likely never be finished, but Johnson knows he’s made progress. He’s working as a realtor, travelling a lot and spending as much time with the people he loves as he can. He’s continued to take avalanche-safety courses and returns to the backcountry each year for a ski trip with friends (including some of his fellow survivors). Telling his story is an important step forward, one he says has been a long time coming.

Johnson still wrestles with big questions: “Why me? What am I here for? What am I supposed to do now?

“I wouldn’t say I have those answers yet,” he admits. But he doesn’t blame anyone for what happened—not his school, not Mr. Nick, not the outdoor education program that he still believes is valuable. And not the backcountry: “Sometimes s–t like this happens. Can you blame a mountain? No. A mountain is just a mountain. Snow is just snow.”