Bye-bye Bay Street

New lawyers are looking beyond big-city firms to put up a shingle in small-town Canada.

Photograph by Nayan Sthankiya

Share

When she was in law school, Amber Biemans always figured she’d practise in the city. After she and her husband had kids, though, she felt the pull of small-town life. At age 26, Biemans joined a firm in Humboldt, Sask. (population 5,900); two years later, she’d bought out a senior partner at the firm who was ready to retire. Making partner at age 28 was an “amazing opportunity,” says Biemans, now 32, but beyond that, “the benefits here are immense,” from the commute to work—which takes all of five minutes—to the close relationships she’s built with clients.

Small-town lawyers like Biemans are becoming an endangered species. As a group, they’re getting older: outside Winnipeg in southwestern Manitoba, almost three-quarters of lawyers have been practising for more than 20 years, says the province’s law society. Rural lawyers who want to retire are having a hard time finding young lawyers to replace them—but at the same time, in Canadian cities, young lawyers are having a harder time than ever finding work. In Ontario, the lack of articling positions has gotten so bad it’s been called a crisis, and the number of students being hired back has gone down, too. Some U.S. law schools are even facing lawsuits from disgruntled ex-students who allege they were misled about their employment prospects after graduation. Newly minted lawyers have typically chased jobs at the big downtown firms, but given the current climate, it could be that some of the best opportunities are in smaller practices, as Biemans found.

This month, Thompson Rivers University (TRU) in Kamloops, B.C., welcomed 65 students to its faculty of law, Canada’s first new law school in over 30 years. Lakehead University, in Thunder Bay, Ont., also recently got the go-ahead to open a law school of its own—Ontario’s first in 42 years, and the only one in the north end of the province. (Lakehead’s first class of 55 students will start in 2013.) It’s worth noting that both law schools share a similar mandate: to train lawyers in relatively remote settings, in the hopes they’ll settle there. This model has already had success at Lakehead’s Northern Ontario School of Medicine, which has managed to attract and retain doctors in the area. About 60 per cent of graduates stay to practise there, says Lakehead president Brian Stevenson, and “another 15 or 20 per cent go to other rural medical practices in Ontario.”

It can seem like a funny time to be adding new law schools, since a surprising number of graduates are struggling to find work. In Ontario, the hardest hit, 12.1 per cent of 2010-11 candidates had yet to find an articling spot as of March, a necessary step to becoming licensed as a lawyer, according to the Law Society of Upper Canada (LSUC), which regulates the province’s lawyers and paralegals. That’s up from 5.8 per cent in 2008. (In June, the LSUC struck an articling task force, and will present a full report next year.)

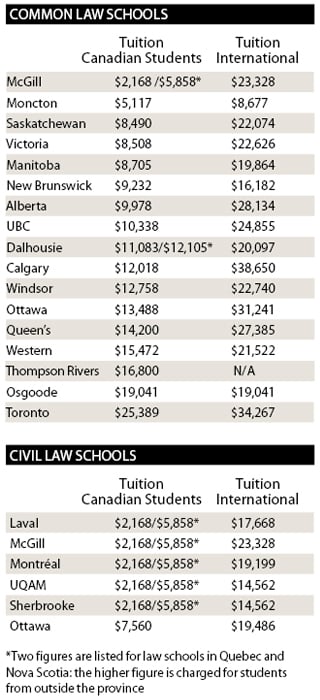

Observers blame everything from a still-shaky economy to increasingly stiff competition—a law degree is more in demand than ever. A growing number of Canadians who can’t find a spot at a law school here are pursuing one abroad, then returning in the hopes of practising. Australia’s Bond University, which teaches courses in Canadian law, has seen a 33 per cent increase in the number of Canadian students enrolled in their juris doctor (J.D.) program from 2007 to 2011. “We think there’s a new normal in Canada,” says Dan Malamet, national director of programming and events for ZSA, a legal recruitment firm. Adds Salima Alibhai, a senior consultant there, “We’ve noticed a big decline in the number of articling positions and hire-backs, and students’ expectations haven’t kept pace.”

Most of these students are chasing opportunities in cities, because that’s where they’re clustered: according to the LSUC, 79 per cent of all articling jobs in the province are in Toronto or Ottawa. There are all sorts of other reasons students might prefer to stay in urban centres, from financial expectations—many will be saddled with debt once they graduate—to social ones. And the bigger urban firms are simply better known. They have the resources to “send teams to recruit on campus, maybe take students out to dinner,” says Scotty Lennox, 25, president of the Dalhousie Law Students’ Society in Halifax. Smaller firms generally won’t recruit on campus, and might not even advertise openings for students (although they may take one on if approached). It’s all pushing young lawyers into the city. Between 2006 and 2010, the Law Society of B.C. surveyed articling students about where they’d like to practise; a whopping 74.6 per cent said the Lower Mainland (in and around Vancouver). Another 8.9 per cent chose Victoria, while 1.5 per cent said northern B.C. and 0.9 per cent the Kootenays.

Still, that seems to be changing. These days, “I get a lot of people who call me and say, I want to relocate to my hometown, find a job at a small firm or hang up a shingle,” Alibhai says. At Lakehead, Stevenson insists there’s a need for law school graduates in the North, and that articling spots will be available for them. “A number of law firms here have reported unused articling positions,” he says. Lawyers say there’s no shortage of work. Karen Drake, a lawyer in Thunder Bay who took part in a task force that worked to get Lakehead’s law school approved, says she’s so busy she sometimes has to turn potential clients away. “I get so many phone calls, but my caseload is full,” she says. Biemans’s firm recently lost an associate, and “the effect has been dramatic,” she says. As she and the other partners pick up the slack while desperately seeking a replacement, “we’re booked solid.”

Michael Litchfield, who started his own law practice in Kelowna, B.C., has spent the last few years trying to address the lawyer shortage in B.C.’s under-serviced communities: he’s head of the Rural Education and Access to Lawyers Initiative (REAL), run by the Canadian Bar Association’s B.C. branch, which aims to address the lawyer shortage in B.C.’s rural areas. As part of the initiative, which was launched in 2009, Litchfield has travelled to law schools all over Western Canada and met with students. “Practising in small communities is seen as a second choice,” he says. “We’ve been trying to change that.” REAL helps place students in summer jobs with firms in rural or under-serviced areas; according to him, about 50 per cent go on to article there, boosting the chances they might stay. (The REAL program is scheduled to end in 2012, although Litchfield says the CBA’s B.C. branch is hoping to extend it.)

The Law Society of Manitoba, meanwhile, has looked at a few different ways to address the pressing shortage of lawyers in rural areas—including a social networking site. “When we did focus groups, we heard that lawyers didn’t like the isolation of practising in a small community,” says CEO Allan Fineblit. To address this, the law society is setting up “sort of a Facebook for lawyers in small communities,” he says, so they can chat with peers even if there aren’t any for miles.

One of the country’s most innovative programs, also in Manitoba, is modelled after a strategy that’s long been used to bring doctors to under-serviced communities: a debt relief program. A partnership between the provincial law society and the University of Manitoba, it will put 20 students through law school over the next five years—all of them with strong roots in the North, or rural parts of the province, who intend to practise there once they’re finished. (For each year they practise in an under-serviced community, 20 per cent of an interest-free loan is forgiven; after five years, they don’t have to pay it back.) Margaret Hillick, a 33-year-old mother of two from Thompson, Man., is the first person to take part; when she spoke to Maclean’s in late August, she was settling into her new life in Winnipeg and eagerly awaiting the start of her semester. “When you move to a new city, there are financial costs associated, and law school is expensive anyway,” says Hillick, a social worker who’s dreamed of attending law school. Without this program, she admits it probably would still just be a dream.

When Hillick graduates, she intends to work in Thompson. “The North is so under-represented,” she says. “I want to help build the community there.”