Canada 150 unhappiness? Blame 1967.

It was a ‘giddy, insane’ year. And the events it set off are at the centre of the national debate unfolding today.

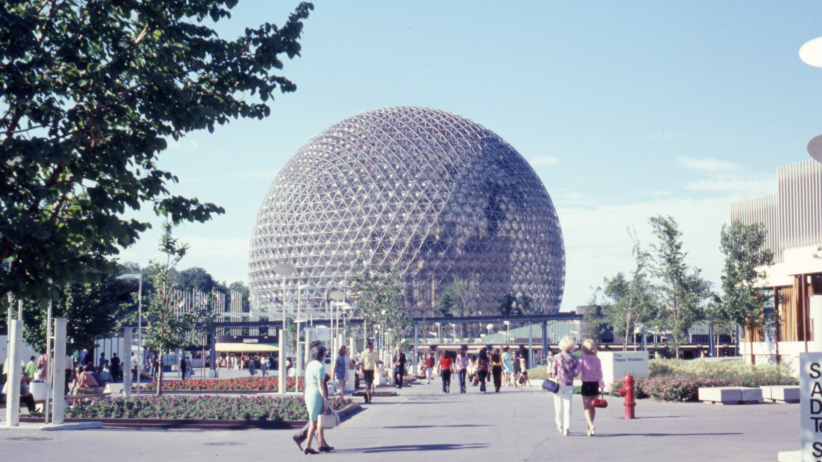

Pavilion of the U.S at the Expo 1967 in Montreal. (Leber/Ullstein Bild/Getty Images)

Share

As July 1 approaches, with as many as 450,000 people expected to assemble on Parliament Hill and stream through the capital region’s various holiday weekend venues, the shadow of terrorist outrages in Europe has caused the Canada 150 celebrations in Ottawa to be enveloped within the most ambitious security operation in the city’s history.

Even if everything comes off without a glitch, the national sesquicentennial anniversary of Confederation, so far, is not exactly shaping up as a replay of 1967, the Summer of Love.

There’s more than a little grumpiness in the national mood.

READ MORE: The Canada Project: 24 Facts for Canada 150

A recent Ekos Poll shows that only a third of Canadians think they’re better off than the generation before them, and over the past decade the proportion of Canadians who say the next generation will be better off has fallen to one in 10. Not everyone is in a celebratory frame of mind.

Last week’s “Colonialism 150” rumpus at the Southern Alberta Art Gallery in Lethbridge, where gallery curators pasted an inversion of the stylized Canada 150 maple leaf on the front door, is just one spinoff in a campaign of sorts that purports to show that this year’s commemorations celebrate “150 years of the Christian, fascist capitalist, colonial project called Confederation.”

There are arguments to be made for that unhelpfully overwrought proposition—or at least it’s easy to get the point of it. But a far more sturdy proposition is that what happened in 1867 has much less to do with the way any of us argue about Canada nowadays than we might imagine. In his just-published book, The Year Canadians Lost their Minds and Found their Country: The Centennial of 1967, author Tom Hawthorn makes the case that 1967 is the year we should be thinking about: “The Canada of 2017 owes more to decisions made in the wake of 1967 than to the negotiations conducted in 1867.”

Until that “happy, giddy, insane year,” Canadians only rarely managed to muster much of an opinion about their country at all. And then, suddenly, we could barely contain ourselves. Hawthorn’s opening essay recalls his Montreal childhood, and his enchantment with the spectacle of Expo 67, the World’s Fair Canada hosted in Montreal that year.

But official spectacles alone didn’t make 1967 the year it became. “For all the public works, all the construction and the flash of Expo 67,” Hawthorn writes,” it was the spirit of ordinary Canadians that best expressed the joy of living in the peaceable kingdom.”

RELATED: What ever happened to Vox Pop Labs’ $600,000 Canada 150 survey?

After a long stretch of boredom and public indifference, something seemed to just bubble up in the weeks before Jan. 1, 1967. Much credit is due to the grand-gesture efforts encouraged by the irrepressible Judy LaMarsh, the secretary of state for Canada at the time, but it was the spontaneity of ordinary Canadians that turned things around.

Several widely watched events were solitary affairs. The 24-year-old welder and heavy equipment operator Hank Gallant endured nine blizzards and -39 degrees Celsius temperatures to walk across Canada, from Victoria to Newfoundland, sleeping under trees and in haystacks along the way, picking up the occasional odd job to pay for his meals. It took him 280 days.

Some commemorations were just quirky and fun: In Smiths Falls, Ont., 500 men stopped shaving, to emulate the bearded Fathers of Confederation. Other efforts were in the vein of the “Indigenous reconciliation” efforts that we tend to think of as some kind of recent innovation: The students at Ottawa’s Laurentian High School donated a 2,000-book library to the far less fortunate students of the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan.

Some commemorations were almost private affairs. Winnipeg’s Margaret English put her cake-decorating talents to work adorning 36 sugar cubes with tiny little paintings of each of the provinces and territories’ official flowers. She gave them to friends. Other contributions were publicity-seeking, wholly eccentric affairs—Nanaimo, on Vancouver Island, organized a bathtub race in the choppy waters of the Strait of Georgia. The event became an annual tradition, attracting entrants from around the world.

It was a global phenomenon, too. The federal Centennial Commission had called for the ringing of bells across Canada at midnight on Jan. 1, 1967, but the people of St. Paul, Alta., taking the cue from their own civic-minded Paul Drolet, wanted to go one better: bells ringing around the world. Drolet conscripted the people of St. Paul into writing letters and working the phones, and in the first moments of 1967, bells rang out, in sequence, beginning in Japan and the Philippines.

Ships in the harbour of Helsinki, Finland, sounded their bells, and the chiming was repeated by ships far out in the Atlantic until the clamour reached Newfoundland. The Quebec Jesuit Gonzague Hudon rang the bells at St. Joseph’s Church in Nazareth. In the English village of Gomshall, in Surrey, 87-year-old Alfred Dowling stayed up late and rang the doorbells of all his neighbours.

There were intensely local celebrations, too. The 504 townspeople of Bowsman, Man., a town roughly 500 kilometres northwest of Winnipeg, brought in the new year with the singing of Auld Land Syne and the fiery climax of their own centennial project: a towering bonfire of outhouses made redundant by the town’s construction of a sewage treatment plant.

Put all that together with Gordon Lightfoot’s Canadian Railroad Trilogy, CBC extravaganzas, the Confederation Train that crossed the country with a rolling museum that ended up hosting 2.7 million visitors—three times as many as anticipated—and the mood changes. The next thing you know there’s the maple leaf on backpacks in Europe. There’s Trudeaumania, bilingualism and multiculturalism, and a persistent national anxiety about the crippling poverty and alienation suffered by so many Indigenous communities.

Everything we celebrated and fussed about and laughed at in 1967 went into building the national stage where we play out the self-loathing, the earnest self-criticism, the hilarious self-deprecation and the striving, passive-aggressive boastfulness that defines Canadian “patriotism” today.

It didn’t begin in 1867. Not even close. It didn’t even start until 1967.