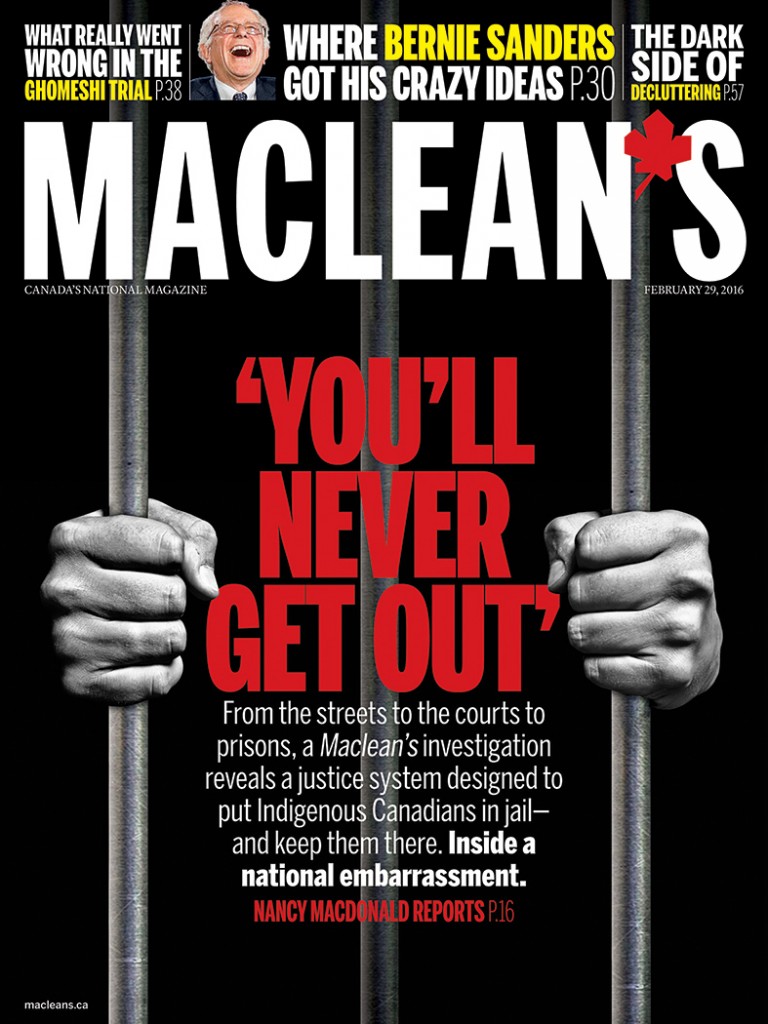

Cover preview: In Canada, justice is not blind

A Maclean’s investigation that spanned nine months has uncovered a system designed to put Indigenous Canadians in jail—and keep them there

Share

In an investigation that spanned nine months into how Canada’s justice system treats Indigenous peoples, Maclean’s travelled across the country, visiting prisons, jails, bail courts and First Nations courts, and speaking with lawyers, judges, inmates and hundreds of Indigenous people about their treatment by police, legal, judicial and penal authorities. It uncovered a system that appears to put as many Indigenous people in prison as legally possible and appears designed to keep them there.

In an investigation that spanned nine months into how Canada’s justice system treats Indigenous peoples, Maclean’s travelled across the country, visiting prisons, jails, bail courts and First Nations courts, and speaking with lawyers, judges, inmates and hundreds of Indigenous people about their treatment by police, legal, judicial and penal authorities. It uncovered a system that appears to put as many Indigenous people in prison as legally possible and appears designed to keep them there.

While admissions of white adults to Canadian prisons declined through the last decade, Indigenous incarceration rates were surging: Up 112 per cent for women. Already, 36 per cent of the women and 25 per cent of men sentenced to provincial and territorial custody in Canada are Indigenous—a group that makes up just four per cent of the national population.

This helps explain why prison guard jobs are among the fastest-growing public occupation on the Prairies. And why criminologists have begun quietly referring to Canada’s prisons and jails as the country’s “new residential schools.”

Also from Nancy Macdonald: Indigenous women share their stories of resilience

In the past decade, the federal government passed more than 30 new crime laws, hiking punishment for a wide range of crimes, limiting parole opportunities and also broadening the grounds used to send young offenders to jail. At the same time, it has been ignoring calls to reform biased correctional admissions tests, bail and other laws disproportionately impacting Indigenous offenders. Instead, it appears to be incarcerating as many Indigenous people as possible, for as long as legally possible, with far-reaching consequences for Indigenous families.

But the problem isn’t just new laws. Although police “carding” in Toronto has put street checks, which disproportionately target minority populations, under the microscope, neither is racial profiling alone to blame. At every step, discriminatory practices and a biased system work against an Indigenous accused, from the moment a person is first identified by police, to their appearance before a judge, to their hearing before a parole board. The evidence is unambiguous: If you happen to be Indigenous, justice in Canada is not blind.

“What we are doing is using our criminal justice system to defend ourselves from the consequence of our own racism,” says Toronto criminal lawyer John Struthers, who cut his legal teeth as a Crown attorney in remote, northern communities. Rather than treat trauma, addictions, he says, “we keep the doors closed.”

Read the full story, and much more, in the latest issue of Maclean’s. Available now for tablet and mobile readers on our new Maclean’s app on Apple Newsstand and Google Play, on Texture by Next Issue, and soon on newsstands everywhere.