Exclusive: Tories move to strip citizenship from Canadian-born terrorist

Case of Saad Gaya, convicted bomb plotter, a major test for controversial new law

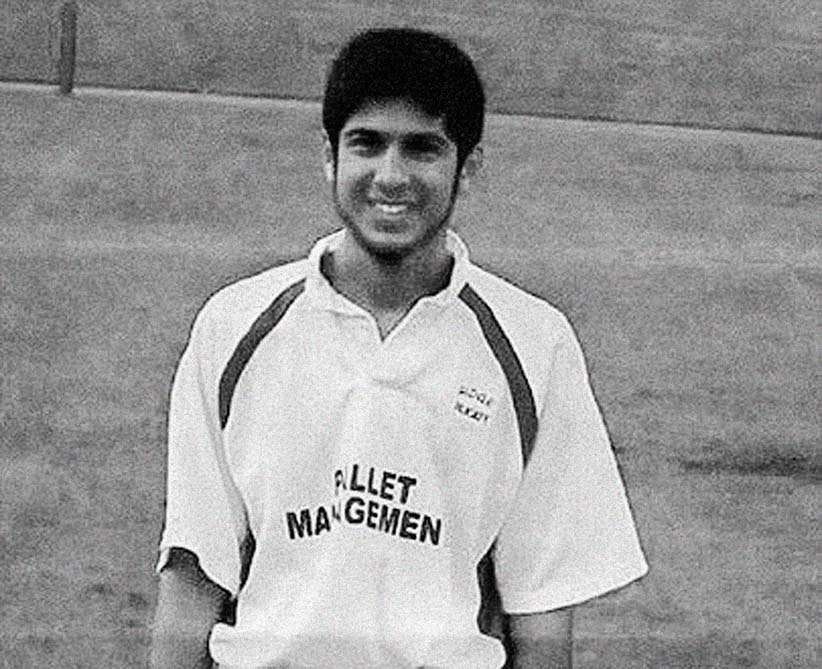

SAAD GAYA

Share

The Harper government is attempting to revoke the citizenship of a convicted terrorist who was born and raised in Canada, Maclean’s has learned—a first under a controversial new law that has triggered intense debate during the election campaign.

Saad Gaya, 27, is believed to be the only Canadian-born citizen (terrorist or not) to ever face the prospect of being stripped of his citizenship. Until now, there was no legal mechanism to undo what has long been considered an irreversible birthright.

A member of the so-called “Toronto 18,” Gaya pleaded guilty to his role in an al-Qaeda-inspired bomb plot and was sentenced to 18 years in prison. Although he was born in Montreal and grew up in Oakville, Ont., the Tories say recently enacted legislation provides the power to rescind Gaya’s citizenship because they believe he is a dual national of Pakistan—by virtue of the fact his parents, who immigrated to Ontario more than three decades ago, were born there.

Gaya, who has never lived in Pakistan, has launched a Charter challenge in Federal Court, arguing that the government’s revocation system amounts to “cruel and unusual punishment” and could have “a sufficiently severe psychological and social impact.”

“For many individuals captured by the new revocation provisions and who would now face deportation, including the Applicant, their other nationality derives from a country with which they have no meaningful connection, have little or no familiarity with the language or culture, and have no family or other support network,” reads Gaya’s court filing, submitted Sept. 18. “The Applicant was born and grew up in Canada. His family is in Canada and has been since before he was born.”

That Saad Gaya was a terrorist is not in dispute. A former honours student at Hamilton’s McMaster University, he confessed to participating in a 2006 conspiracy to detonate bombs in southern Ontario in retaliation for Canada’s military mission in Afghanistan. Although a judge concluded he was not the plot’s driving force, he was a loyal, willing underling who followed every order; the day he was arrested (June 2, 2006), police videotaped him at a north Toronto warehouse unloading what he believed to be a truckload of explosive fertilizer.

Gaya himself described his criminal behaviour as “shameful,” “politically naïve,” and “irrational.”

Yet despite his undeniable guilt, the Tories’ push to revoke Gaya’s citizenship presents an uncomfortable (and potentially unconstitutional) possibility: that a person born in Canada could lose his Canadian status and be deported to a country he’s never known—all because his parents were born there and, by extension, passed their dual nationality onto him.

“Exiling someone who was born in Canada, and who has never been to the country they’re going to be deported to, is a horrible punishment,” Lorne Waldman, Gaya’s lawyer, tells Maclean’s. (Again, immigration experts say no one born in Canada has ever had his citizenship revoked. Before the new law came into force, only a naturalized Canadian who acquired citizenship through fraud or misrepresentation could be stripped of that status.)

In effect since May 29, the Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act was portrayed by the Conservatives as another critical tool to combat the “ever-evolving threat of jihadi terrorism.” The law allows the government to revoke the citizenship of anyone convicted of serious crimes against Canada’s security, including treason, espionage and terrorism—providing that person is a dual national who holds citizenship in a second country. International treaties do not allow Ottawa to leave a person stateless, which means terrorists who hold only Canadian citizenship can’t be stripped of their status.

Critics say the law, introduced as Bill C-24, creates “two-tiered” citizenship because the harsh new rules apply only to dual nationals, not to the vast majority of Canadians. They also argue that revocation essentially amounts to banishment for those who fit the criteria—and that the Charter of Rights and Freedoms protects even an admitted, convicted terrorist from being punished twice for the same crime.

“The concern is the law creates two classes of citizens,” says Peter Edelmann, a Vancouver immigration lawyer. “Two people who commit the exact same offence are subject to different consequences: you have banishment as a punishment for certain people, and not for others. For me, it’s not a question of assessing: ‘How do you punish terrorists?’ It’s a question of: ‘Are dual nationals less Canadian?’ If the answer is yes, I think that has some very profound implications.”

Those potential implications were thrust into the centre of the federal election campaign last week when the National Post reported that Zakaria Amara—the confessed ringleader of the “Toronto 18” bomb plot, now serving a life sentence—became the first candidate to have his citizenship revoked under the new law.

Born in Jordan, Amara immigrated to Canada as a young boy before growing up to become a prime target of the country’s spy agency, the Canadian Security Intelligence Security (CSIS). A gas-station attendant in Mississauga, Ont., Amara was so obsessed with Internet jihad videos and avenging the “slaughter” of Muslims that he hatched what a judge later described as a “spine-chilling” plan: a trio of truck bombs aimed at the Toronto Stock Exchange, the downtown offices of CSIS, and an unnamed military base. It’s “gonna be kicking ass like never before,” he told an accomplice, unaware of the police wiretap recording their words.

With the help of an undercover informant, the RCMP arranged a sting operation, delivering what Amara thought was three tonnes of ammonium nitrate to complement the remote-controlled detonators he had already built. Saad Gaya was among those who met the truck at the warehouse. “It is difficult to put into words Zakaria Amara’s degree of responsibility,” Justice Bruce Durno said during his 2010 sentencing hearing. “He was the leader and directing mind of a plot that would have resulted in the most horrific crime Canada has ever seen.”

Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau and NDP Leader Tom Mulcair have both vowed to scrap the revocation law if their respective parties prevail on Oct. 19. “A Canadian is a Canadian is a Canadian,” Trudeau told Prime Minister Stephen Harper during the Munk Debate on foreign affairs on Sept. 28. “You devalue the citizenship of every Canadian in this place and in this country when you break down and make it conditional for anyone.”

“A few blocks from here, he would have detonated bombs that would have been on a scale of 9/11,” Harper replied, referring to Amara, but not naming him. “This country has every right to revoke the citizenship of an individual like that.”

The government has alerted a handful of others that their citizenship could be in jeopardy, including Asad Ansari, a fellow “Toronto 18” convict who is now free; Hiva Alizadeh, an Iranian-Canadian serving a 24-year sentence for plotting al-Qaeda bombings; and Misbahuddin Ahmed, Alizadeh’s co-conspirator, who was sentenced to 12 years in prison. Like Gaya, Ansari and Ahmed have launched their own constitutional challenges in Federal Court, fighting to have the law struck down before Ottawa has a chance to apply it in their cases.

But Gaya’s predicament is especially unique. As the only Canadian-born convict targeted for revocation so far, his case raises potentially troubling questions about just how wide the net should be cast—if at all. Voters who may agree that a foreign-born terrorist should be stripped of Canadian citizenship may not be as comfortable with the law being applied to a born-and-raised Canadian. As Toronto lawyer Rocco Galati argued while Bill C-24 was being debated: “Anyone who is born on Canadian soil is a Canadian citizen. You can’t take that away.”

The specifics of the government’s case against Gaya may prove equally unsavoury to some Canadians.

In early August, a senior immigration official mailed a Notice of Intent to Revoke Citizenship to Gaya’s current home at Warkworth Institution, a medium-security facility near Brighton, Ont. The letter acknowledges that Gaya was born in Canada, but claims he is a citizen of Pakistan by descent because his father, who moved to Canada in 1977, and his mother, who immigrated here in 1981, were both Pakistani-born.

But the paper trail gets somewhat confusing. The notice goes on to acknowledge that Pakistan did not recognize dual citizenship when Gaya’s parents swore their oaths as Canadian citizens in the 1980s, so they were technically no longer Pakistanis when their son, Saad, was born in Montreal on Nov. 17, 1987. However, the Harper government now says the parents’ dual citizenship was retroactively reinstated when Pakistan passed an updated citizenship law in May 2004.

Which also means, according to Ottawa, that Gaya suddenly became a Pakistani citizen, too—making him a dual national now eligible for revocation under the new Act, despite the fact he was born here.

Gaya disputes that conclusion. “The Applicant has never applied for Pakistani citizenship and denies that he has Pakistani citizenship,” his court filing reads.

The government has yet to respond to Gaya’s court action, and a hearing date has not been set.

Gaya pleaded guilty in 2009 to participating in a terrorist group that intended to cause an explosion likely to cause serious property damage, bodily harm or death. He then proceeded to read a lengthy statement to the court, accepting full responsibility for his “shameful” actions but insisting that “right from the outset of my involvement in all of this, I was given assurances that no one would get hurt and that this was not going to be like the London bombings of 2005.”

“I am not someone who has grown up in a hate-soaked environment, brainwashed to believe that I am part of some eternal war against the Western civilization,” he continued. “That is not who I am and these are not the values that are instilled in me … I did not take part in this crime out of hatred against this society or its people. I really believed at the time, albeit incorrectly, that by participating in this scheme I would only be assisting the Afghan population in determining their own future without any outside interference. I was young and politically naïve. Today, however, I recognize how irrational and unreasonable this line of thought was. My views have matured and I know with certainty that I will never commit such a mistake again.”

Gaya, who turns 28 in November, is eligible to apply for parole next year. What happens when he’s eventually released—and which country he’ll live in—is suddenly much less clear.