Pollocks, or bollocks? Lawsuit claims paintings thought to be fakes are real

A lawsuit by David Mirvish claims three Jackson Pollock works thought to be forgeries are genuine

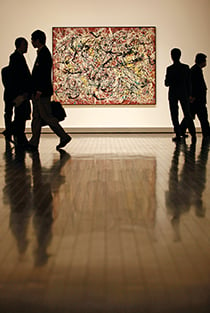

Yuriko Nakao/Reuters

Share

Its provenance was mysterious, and the painting had already failed to impress a committee of authenticators, who refused to certify Untitled 1949 for fear it was a forgery never touched by its purported author, the mercurial abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock. That skepticism scuttled the painting’s sale, to a Goldman Sachs banker, whose $2-million purchase was contingent on a finding it was genuine. Still, David Mirvish, the Toronto impresario and art collector, wanted in. In 2003, according to court documents, Mirvish told Knoedler & Company, the venerable New York art gallery handling the Pollock, that despite these authentication troubles he’d be “delighted to have the opportunity to purchase” the painting—for $2.5 million.

Today Untitled 1949 and two other Pollocks he purchased or invested in through Knoedler are at the centre of a lawsuit Mirvish filed last month in New York against the gallery, which closed in 2011 after 165 years in business amid allegations it dealt in forgeries. (Knoedler has said the closure was a business decision unrelated to the controversy.) But although Mirvish’s suit is one among a number filed against the gallery, all related to a single collection of purported works by masters such as Pollock, Mark Rothko and Robert Motherwell, now widely thought to be fake, Mirvish’s differs in that he maintains his three paintings are genuine. (Mirvish directed questions to his lawyers, who did not respond to interview requests.)

The suit offers a tantalizing glimpse into the trade in high-end art at a time of soaring prices, forgery scandals and proliferating litigation. It is a world that has always operated according to its own opaque rules. “No other multi-billion-dollar-a-year legitimate industry has such a reliance on handshakes, cash transactions and purchases without provenance,” says Noah Charney, founder of the Association for Research into Crimes against Art and author of the novel The Art Thief.

Mirvish bought Untitled 1949 in 2003, under a complex arrangement that, the suit says, saw him borrow half the cost from the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, the other from Knoedler itself, with a promise that he and the gallery would split the proceeds of its resale. By 2007 he’d bought another Pollock from Knoedler—for $4 million, with the gallery again loaning him half that sum—and invested $1.6 million in a third. All three works stayed in Knoedler’s possession, on the understanding the gallery was “attempting to sell [them]” for profit, the suit says. The gallery’s closure meant it did not keep to that bargain, which, according to the suit, Mirvish sees as constituting a breach of contract. Now Mirvish is out two Pollocks and hasn’t been repaid his stake in the third, meaning Knoedler has, to use the suit’s language, been “unjustly enriched.”

Known for bringing Les Misérables and The Lion King to Canada, Mirvish is no dilettante. He opened his celebrated David Mirvish Gallery on Markham Street—just across from his father’s retail paean to glitzy kitsch, Honest Ed’s—in 1963, when he was still a teenager (he closed it in 1978). His collection remains so substantial that Mirvish and architect Frank Gehry have plans for a Toronto museum dedicated to it. Perhaps that is why his suit contains so many references to his own expertise. The filing says he put money down on the Pollocks based on information supplied by Knoedler, “as well as Mirvish’s independent judgment that the works are authentic.” Nevertheless, one of these paintings, which Knoedler sold to a London hedge fund manager in 2007 for $17 million, was later found to have been executed using pigments not commercially available until after Pollock’s death. It now appears that Knoedler, which reportedly settled with this buyer, took back possession of the iffy canvas.

Mirvish isn’t alone in maintaining the paintings are real, including the one Knoedler settled over. So too does Ann Freedman, Knoedler’s former president and Mirvish’s principal contact there. (Mirvish is not suing Freedman; indeed, they share the same lawyer.) Of course, anyone can claim to be an art authentication expert. “The field is not regulated,” says Milko den Leeuw, a Dutch restorer and organizer of Authentication in Art, made up of experts aiming to clean up the business. That will be tough. Collectors are so litigious that some artist’s foundations—like Andy Warhol’s, which lost millions defending a suit filed after it failed to certify a purported Warhol print—have disbanded their authentication boards altogether. “The Pollock market is difficult because there is no generally accepted authority to authenticate them,” says Peter Stern, who has practised art law for over 30 years. That hasn’t stopped many observers from drawing their own conclusions about the Mirvish Pollocks. Says Stern: “I have not heard of anybody that believes the works are authentic besides Ann Freedman and David Mirvish.”