How banning bottled water can backfire

Banning bottled water is supposed to benefit the environment and consumers, but might end up doing neither

Share

Having announced Montreal will ban single-use plastic shopping bags as of Jan. 1, 2018, the city’s mayor, Denis Coderre, recently set his sights on his next target—erasing plastic water bottles from the city.

While the move drew hackles from beverage companies, it was cheered by environmental groups and community leaders who have long viewed bottled water as wasteful and polluting. (Never mind this is the city that dumped nearly five billion litres of raw sewage into the St. Lawrence River last year.) But it turns out banning bottled water might not have the green, consumer-friendly result its supporters hope. If anything, it could turn out to be a boon for the bottled sugar-water business instead, and potentially fill trash bins with even more plastic.

That’s the finding of a researcher who studied what happened at the University of Vermont after the school banned the sale of plastic water bottles on its campus in 2013.

Expectations were high. The school threw a “retirement party” for the plastic bottle, where it erected a sculpture made of 2,000 used plastic water bottles. Refillable water bottles were sold to students for $2 each, while the university retrofitted 68 water fountains with new spouts to fill them. It launched an education campaign to promote the new policy to students, and taste tests were held to see if students could tell the difference between bottled and tap water.

Yet in the months following the ban, students didn’t stop reaching for the plastic bottle, according to Rachel Johnson, a nutrition professor at the University of Vermont who published her findings last year in the American Journal of Public Health. Instead, they consumed even more.

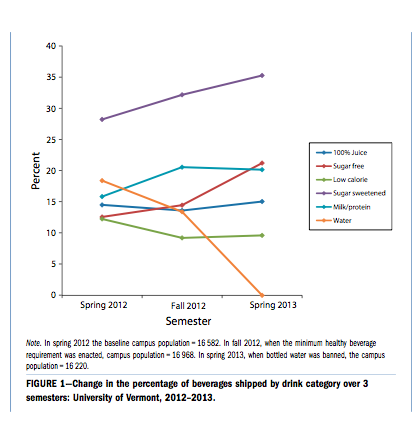

In the spring semester of 2013, following the ban, shipments of plastic bottles to eight campus locations increased to an average of 26 per student from 24 during the same semester the year before, when bottled water was still available. Rather than line up at the new water fountains with their reusable bottles, students instead reached for bottled soda, juices, or sugar-free drinks, which often use thicker plastic than plastic water bottles.

The following chart from the study shows the change in plastic bottle consumption.

To make matters worse, students also consumed more calories, sugars, and added sugars per capita than before the ban. In other words: you can lead students to tap water, but you can’t make them drink.

“I understand the point about limiting plastic that goes into the waste stream by removing bottled water,” says Johnson, one of the study’s co-authors. “But to remove bottled water and then continue to sell unhealthy sugary drinks seems to defeat any public health goals. You’re simply taking away a healthy choice.” Which, she says, is why many public health advocates oppose restricting bottled water where bottled sugar water is sold.

At a time when bottled water is on track to outsell carbonated drinks by 2017, the decline in soda consumption is, as the New York Times recently put it, “the single largest change in the American diet in the last decade.” Annual soda consumption in the U.S. has declined for more than 10 straight years and bottled water is a major factor in slowly washing cola out of the market. Every bit helps in the battle against obesity, diabetes, heart disease and many other public health problems associated with excess sugar. But with these bans, says Johnson, “you’re basically taking away plain unflavoured water and continuing to sell sugar water. As a public health advocate, that doesn’t make any sense to me.”

So as Coderre considers sending plastic water bottles into retirement, he may need to consider what’s to come: Montrealers filling up on sugary pop instead and more plastic bottles ending up the garbage.