How Chanie Wenjack chose Joseph Boyden

Artists of all stripes are creating new works to honour the little boy who ran away from residential school 50 years ago this month. Here’s why.

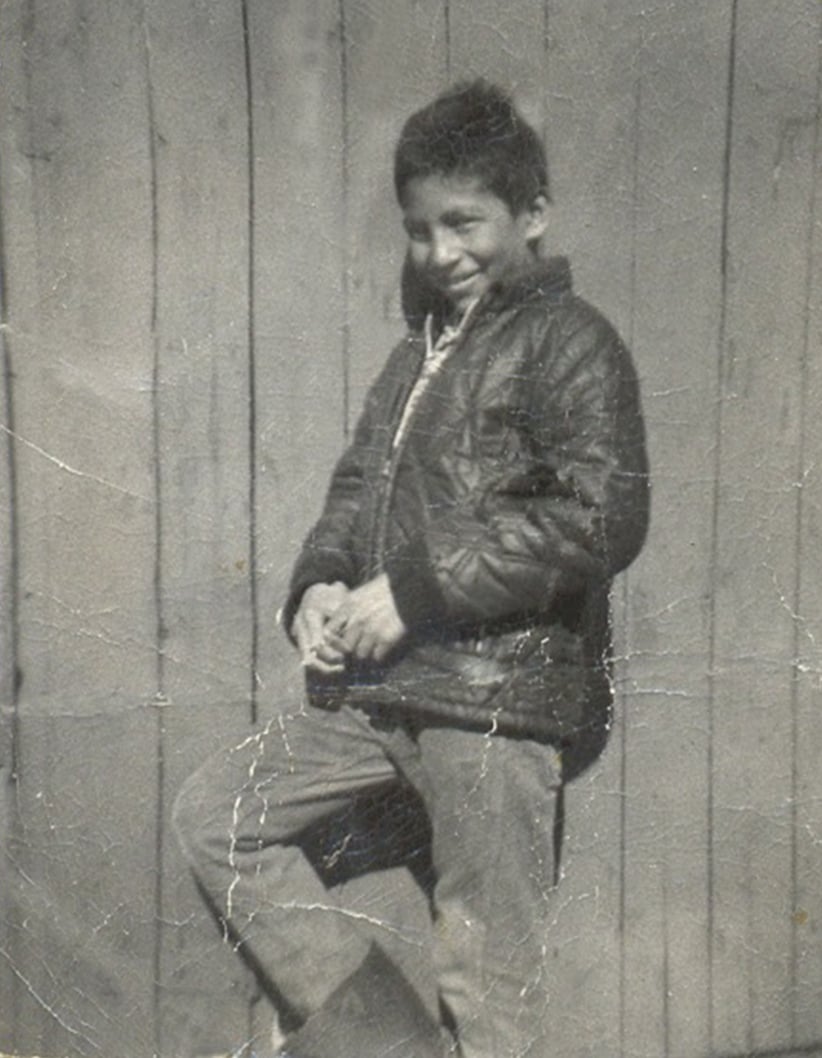

Chanie Wenjack (Wenjack Family)

Share

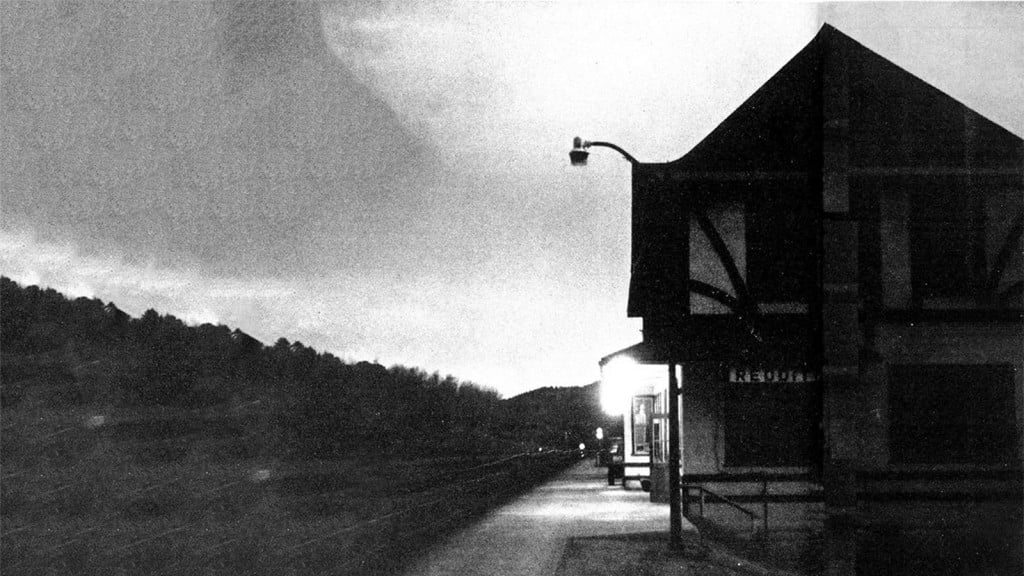

The story has all the hallmarks of great tragedy: an innocent boy lost in the vast wilds of northern Ontario in late October. He’s desperately trying to make his way home as the weather begins its brutal turn. Underdressed for these harsh wilds and with nothing but a few matches in his pocket, he’s starved and shivering. He’s driven by the simple desire to be back home with his parents and sisters and two beloved dogs. But what’s most frightening is that the boy is pursued by a dark and sick menace even as his illness-wracked body begins to weaken. What this poor child doesn’t understand as he limps along a lonely stretch of railroad tracks, night falling and a hard sleet pelting his wretched form, is that home is an impossible 600 km away.

What makes this story even more tragic is that it’s true. The boy’s name was Chanie Wenjack, a 12-year-old Ojibwe boy who was found dead beside that lonely stretch of railroad tracks 50 years ago, on Oct. 22, 1966. He’d run away from Cecelia Jeffreys Industrial Indian School a number of days before, on Oct. 16, a Sunday, with two friends who were brothers. None of them had planned this escape on that unseasonably warm autumn afternoon, scrambling over a chain link fence and then following a secret path so many of the schoolchildren had used before to skirt around the town of Kenora and into the bush in their attempts to just get home. All to this point had returned voluntarily or had been caught, but Chanie and the two brothers were especially driven.

A few years ago now, Mike Downie, the brother of the Tragically Hip’s singer Gord Downie, found an article written in this very magazine way back in 1967; he introduced it to Gord, and then Gord to me. The author, Ian Adams, deftly recounts Chanie’s escape and sad demise, as well as the ensuing public inquiry into his death, the first that I am aware of in Canada in regards to these schools. The all-white jury came to a number of conclusions, including this: “The Indian education system causes tremendous emotional and adjustment problems.” The jury also requested that “a study be made of the present Indian education and philosophy,” asking, simply, “Is it right?” I’m not sure who in provincial or federal government ever read any of these findings. I assume it didn’t make its way up many chains of command at all. It took 30 years after Chanie’s death for the last residential school in this country to close its doors, in 1996.

I don’t want to assume much on Gord’s behalf, but I think it’s safe to say that the image of this little boy just trying to get home haunted him as much as it did me. Mike and Gord and I bandied about a few ideas for a short time, a possible collaboration of some kind—maybe a small book followed by a film—but ultimately we ended up going into our own creative corners to work individually, keeping each other abreast of what we were doing. It was Gord who was first struck by the idea of creating something that could be released on the 50th anniversary of Chanie’s passing. Gord, along with powerhouse musicians Kevin Drew, Kevin Hearn and others went into the studio and created Secret Path, a sparse and gorgeous 10-song record encompassing poems Gord had written about Chanie. Gord then asked the acclaimed graphic novelist and artist Jeff Lemire to create a book in images, telling the story on the page that acts as a beautiful new dimension while listening to the record.

In my own corner, I’d been working on a novel called Seven Matches I hoped to finish in time for an October 2016 release date. I got so close, but realized that if I pushed too hard and too fast it wasn’t going to work. Once you put a novel into the world, you can’t just clear your throat and excuse yourself and ask for it back so you can make it better. After months of rushing to try and finish it, with nights of lost sleep and worrying my fingernails to the quick as my deadline approached, my brilliant friend and publisher, Nicole Winstanley at Penguin, sat down with me and gently urged me to take a breath and a step back. She knows me well. She could feel my stress.

She understood the conundrum: not only were Gord and artistic company putting out Secret Path in the coming October, but I had asked a few amazing Indigenous friends if they’d create their own pieces as well. The Metis filmmaker Terril Calder was hard at work on her haunting stop motion film called Keewaydeh, and the DJ collective and genius music makers A Tribe Called Red had also come on board and included some spoken word tracks on their album We Are The Halluci Nation, dedicated to the young boy. And here I was, lamely about to tell everyone that I just couldn’t get that novel done in time.

The idea of a number of artists of different backgrounds releasing their works into the world on the 50th anniversary of that boy’s passing, was too important to give up on.

We’d all agreed to release our creations unannounced near Chanie’s anniversary, maybe create a ripple effect as we got most Canadians to hear his name from many different quarters and for the first time, a name so familiar and yet so foreign on an English tongue. Wenjack? Wenjack. What does it mean? Who is he? All involved and toiling on our projects want Canadians to feel our gathered breath as each of us, in our own small way, try to breathe back life into a child who died so unnecessarily, so tragically, and almost, almost forgotten.

Nicole suggested I write a long story, a novella, in commemoration instead. Nicole’s never steered me wrong. And the act of being channeled by the boy named Chanie Wenjack and by the manitous, the spirits of the forest who follow him and comment upon his plight, made me fall back in love with the act of writing again.

Nicole suggested I write a long story, a novella, in commemoration instead. Nicole’s never steered me wrong. And the act of being channeled by the boy named Chanie Wenjack and by the manitous, the spirits of the forest who follow him and comment upon his plight, made me fall back in love with the act of writing again.

But why this particular boy? Why did we all choose to make Chanie Wenjack our focus when the brutal fact of the matter is that we had literally thousands of Indigenous children who also perished in residential schools we might have morbidly considered? I’m being asked this a lot this last week or so. I can only answer this question for myself. All I can say is this: I believe that Chanie Wenjack chose me, and not me him. Only a single photo of Chanie exists, a photo that his sister Pearl was kind enough and tough enough and giving enough to share. A sepia-toned and worn print of a young Ojibwe boy with black, tussled hair, the boy leaning slightly on a pine wall outside somewhere north, with one skinny leg crossed over the other all casual, his rubber boots too big for him and his hands held together in the slight grip we all sometimes do that betrays a bit of nervousness, possibly, at being photographed. But what’s most striking in the photo is his face. Sweetness is the word that comes to me when I stare at it. His eyes are slightly narrowed and his round cheeks highlight a smile that tells you everything you need to know. He’s good. He’s kind. He’s shy. He’s going to be something great one day. He already is, and I can just bet that he makes every one of his family feel a tinge of warmth, of happiness, when he walks into a room. Chanie’s smile chose me. It dared me to try and decipher him. Chanie Wenjack’s cruel and unnecessary death 50 years ago, I realize, isn’t a story of innocence lost. It is Canada’s story of innocence violently taken.

MORE: Chanie Wenjack wasn’t the only runaway. Read the stories of two more boys.

Why Chanie Wenjack, you might still ask? Because Canada is a haunted house. A really smart man I know named Stephen Marche dropped that line on me one day awhile back. It felt like he’d pulled the pin from a grenade and casually dropped it in my lap. Canada is a haunted house. He didn’t explain anything else or ask me for anything in return, just said this and left it for me to either defuse or let explode. I’ve been thinking about this a lot the last while.

Another friend, the Kwagiulth artist Carey Newman, challenged me further to explore this. This is what I feel: we Canadians have a lot of bones in our basements. Secrets in our attics. Stains on our bedsheets that we’ve carelessly flung into the hamper and left to fester. The sepia glimpse of a sullen Cree child’s face at her school desk when we walk our own kid to school on a brilliant autumn morning. The flash of an Inuit boy dead by his own hand forcing us to close our closet door too fast. The weeping of a young Sto:lo girl left raped and bleeding by her teacher chasing us up from our darkened laundry room.

Maybe the statement needs to become a question: do we want to live in a haunted house for the rest of our lives?

The time for a national reckoning has arrived. The original peoples of Canada have suffered through a multi-generational cultural genocide. We have experienced genocide as if it’s a tsunami in slow motion. We have witnessed a brutal tide rise up for seven generations, destroying homes, swallowing families, drowning our children.

But the Indigenous people of our country are nothing if not resilient. And patient. And tough. This tsunami has reached its high-water mark. It finally recedes. It is up to all of those who are brave enough, resourceful enough, kind enough, tough enough; it is up to the artists, but also the construction workers and doctors and cab drivers and lawyers and the unemployed, the cops and baristas and housewives and fathers-to-be, to become the beachcombers of this nation, to wander the wrecked shorelines and gather the remnants, the glittering detritus of so many destroyed lives and begin to help in patching it back together again. We all know that it won’t be as it once was. We can’t go home that way again.

Maybe, though, maybe, something like the many retellings of Chanie Wenjack’s life, or the gorgeously subversive paintings of Kent Monkman, or Carey Newman’s Witness Blanket Project, or Gord Downie’s Secret Path, or Katherine Vermette’s The Break will show all of us not just what was lost but also what hasn’t been lost. Can’t be taken away. Perhaps there is such a thing as an exorcism through art.

The great tragedy, the great stain of our country, is that Chanie’s story is shared by thousands of Indigenous families across our country. Thousands of children were forcefully ripped from their homes and their parents and their languages and religions and songs and siblings and cultures, only to die while in the custody of strangers sworn to their care. Chanie Wenjack isn’t alone. This needs repeating: The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has collected the names of thousands of children who perished while in these schools and never returned home. The TRC fears the number may be as high as 30,000.

Please, I ask you, dear reader, don’t skip over that number. Please contemplate it. Take the time and effort to count out 1,000 pennies and then toss them onto the floor of your kitchen. Then do it many more times. On the next clear night, sit with your own child under the dizzying array of stars and begin counting till you both become too tired. And do this every clear evening for a whole summer. Pick up where you left off and continue it the next summers again. Perhaps sit down one day soon and begin to read the names of the children the TRC has collected so far. Whisper them, shout them, absorb them. Just don’t let them be forgotten. Think of them as your own children. But for Chanie’s sake, and the sakes of so many thousands more, let’s all decide not to live in a haunted house any longer.

Chanie Wenjack wasn’t alone. We’ve told the tragic and forgotten stories of two more boys escaping residential school. With your help, we can tell more. Find out how, here.