How easy is it to buy a secret shell company in Canada? Very.

The Panama Papers listed Canada as a good place to incorporate an anonymous shell company. One study has shown it’s disturbingly simple to do.

An aerial photo of Toronto (Shutterstock)

Share

As the fallout continues from the Panama Papers, with the revelation that British Prime Minister David Cameron benefited from his father’s offshore trust and the resignation of FIFA’s ethics judge, the anticipation that a Canadian bombshell would emerge has waned. While 350 Canadians reportedly appear within the 11.5 million documents from the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca, there have so far been no political leaders from this country linked to the offshore accounts, nor have any celebrities been named and shamed for stashing their millions offshore, as they have elsewhere.

However, when the Panama Papers were first leaked, several reports noted a seemingly peculiar Canadian reference in the reams of documents. As the firm’s lawyers guided clients through the process of setting up their offshore accounts, one of the countries recommended as a place to hide wealth was, of all places, Canada. As the Toronto Star noted, Mossack Fonseca marketed Canada “as a place to incorporate anonymous companies”

Jason Sharman, a political science professor at Australia’s Griffith University and author of several books on international money laundering and global tax regulation, knows first-hand how easy it is to set up an anonymous shell corporation in Canada. In researching his 2014 book Global Shell Games, Sherman and his team of researchers tested how compliant countries were with international regulations governing the transparency of companies. The researchers approached 3,700 firms that provide shell companies across 182 different countries via more than 7,400 emails, posing as both low-risk clients (the “placebos” in their experiment) and potentially high-risk individuals—money launderers, corrupt officials, and terrorist financiers. (For instance, for the latter they claimed to be residents of one of four nations associated with terrorism and working in Saudi Arabia for an Islamic charity.)

What Sharman found was that firms in developed countries like the United Kingdom, Australia, the United States and Canada were three times worse at enforcing transparency rules—such as requiring proper identification—than developing countries and widely-recognized tax havens.

In an interview Sharman recalled his team approaching one Ontario firm using a fake name and fake identify through email. He was never asked to prove his identity with a copy of his passport. Instead, he was told to type in the name of the shell company he wanted to set up on the firm’s website, and that the firm would take care of the rest. All he had to do was send the money.

While there are non-criminal reasons someone might want to set up a secretive shell company, international transparency rules are in place to deter those that are engaged in illegal activity from doing so. Which is what Sharman found troubling about the ease with which his researchers were able to buy anonymous companies in countries like Canada. “The thing about Canada that makes it attractive to criminals, ironically, is that it’s not associated with criminality,” he says.

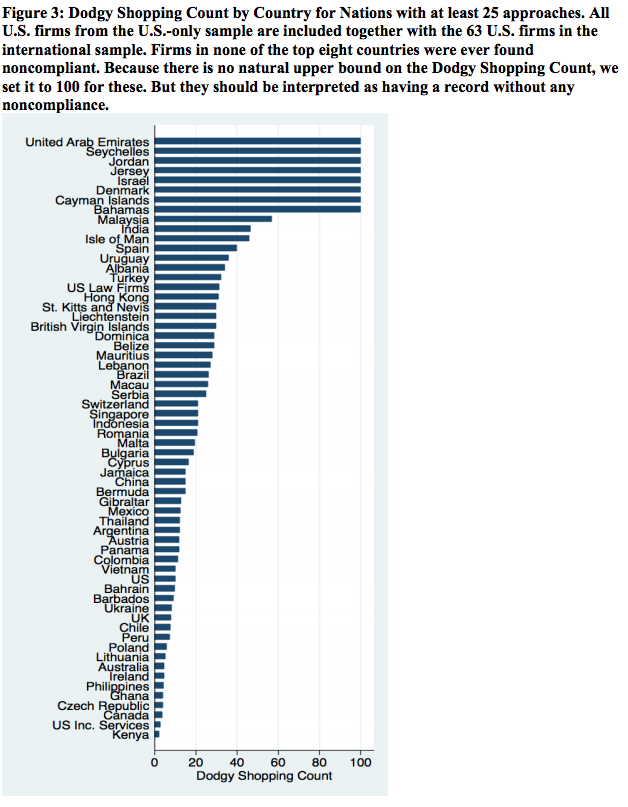

So just how poorly did Canadian firms do? To rank countries the researchers created a “Dodgy Shopping Count,” an index that measures the average number of providers a particular kind of customer would have to approach in each country before being offered an untraceable shell company. The lower the score, the easier it is to set up anonymous shell corporation.

Even compared to what many would perceive as the classic tax havens—Switzerland, Belize, Panama—Canada fared far worse. (In the figure below, Canada is third from the bottom.)

How is this possible? Sharman points to Canada’s enthusiasm for deregulation, a common trend among many English-speaking countries over the last few decades. Despite the best intentions of making it easier for entrepreneurs to set up small companies, it also made Canada more attractive to those seeking to hide their wealth.

Canada also offers the added benefit of efficiency. “If you’re looking to set up a company in China, it takes three to six months,” Sharman says. “In Canada, it’s a matter of days.”

Canadian law enforcement is also perceived to have shorter arms. U.S. firms may have scored lower than Canada in the study, but if police trace any illegal activity to an anonymous account, “Canadian law enforcement is unlikely to kick your door down and haul you away from your place overseas,” he says. “U.S. enforcement does have a habit of doing that every so often.”

Sharman has no need to worry about the Mounties knocking on his door one day for using a false identity in his filings. When setting up his anonymous shell corporation in Canada, he did practically everything necessary except sign his fake name on the dotted line. He simply wanted to test how easy it would have been. Besides, he says, he had already set up a several anonymous shell corporations in other countries using his actual name. Not that anyone would ever know.