Immigrants in Canada, and the secrets some of us keep

What The Atlantic’s story ‘My Family’s Slave’ reflects for many of Canada’s immigrants, and their complicated relationships to their new homes

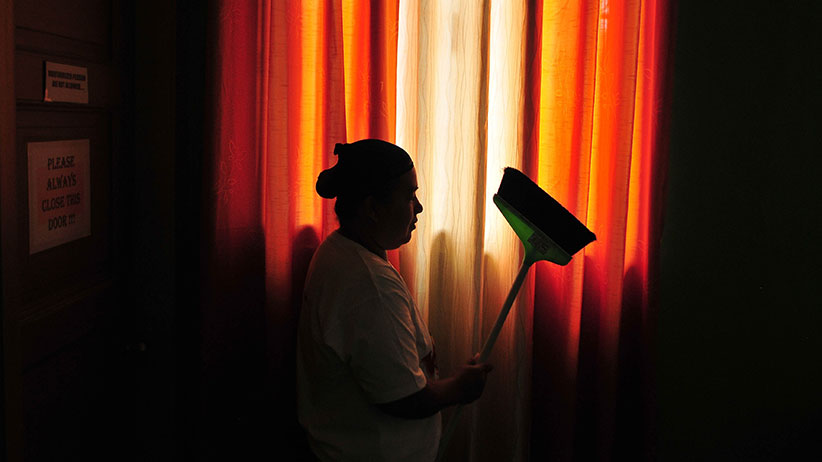

Filipino applicants undergo an intensive course on housekeeping on September 06, 2013 in Manila, Philippines. Due to the rise of household help applicants going to different countries in Asia and the Middle East, the Philippine Government required that all workers undergo courses with accredited centers to be able to meet standards abroad. (Veejay Villafranca/Getty Images)

Share

When the Atlantic‘s June cover story “My Family’s Slave” first appeared online, there was—in what now seems commonplace for things that go viral—a predictable and self-actualizing spectrum of responses. The late Filipino-American journalist Alex Tizon’s story about his family’s servant was greeted by shock, then sadness, followed by anger and disgust, and then a mix of indignation and shame. The latter was especially true of Filipino voices attempting to add nuance to the conversation, and to contextualize these domestic service arrangements—variously known as utusan, or katulong, or kasambahay in Filipino parlance—within the medley of that country’s history and cultures.

Dismissing unique peculiarities of Filipino culture and power dynamics as we try to dissect by railing at us is Western supremacy in action.

— Nik (@iwriteasiwrite) May 17, 2017

For immigrants, especially those from old-world, traditional societies, Tizon’s essay surfaced uneasy truths about our own families’ histories and involvement with servitude, indentured or otherwise. Share the Atlantic article with a co-worker or friend of yours with ties to Asia, the Middle East or Africa, and you may not quite see the level of shock you expect. Or it will be there, as I saw from my mother when I read the essay to her—but there will also be an undercurrent of discomfort. That discomfort stems from the fact that for many of us immigrants, having servants in the house was a routine fact of our lives.

The story of Eudocia Tomas Pulido, called “Lola” by Tizon in his article, is admittedly an extreme example. The fact that she was coerced into migrating to America with Tizon’s family, and then forced to serve them without pay until his mother’s death, is incredible. Nevertheless, having live-in domestic servants is a common phenomenon “back home”, but here in Canada is something reserved mostly for the wealthy.

diaspora kids pretending they don’t recognize slavery when they see it even though they come from cultures with housemaids/houseboys. kay.

— تاز المشاكس (@RuffneckRefugee) May 16, 2017

In my case, from my earliest memories in Nepal, I remember a revolving door of servants, almost all women, who lived with us and worked for us, one at a time. I can recall nearly ten different faces, but only the names of two. One of the last ones, before my mother decided to move to Canada with me and my two brothers, had a young child with her. We played with him, ate with him, and bullied him as his mother prepared food and washed our clothes and cleaned the house and did everything else that a servant does. He was too young for school when he was with us, so he would often be waiting at the balcony, with his assortment of toys discarded by us, when we returned home from school.

By the standards of Kathmandu, the capital city where we lived as Tibetan refugees, we straddled the worlds between working and upper-middle-class. Not every family had hired domestic help; sometimes it was a relative from one of the thousands of villages dotted across the hills and plains of Nepal. But we had help.

All the servants we employed were paid, unlike Pulido. But Nepal also has its own version of katulong; we called them kamaiya.

The Kamlari/Kamaiya slavery of the western lowlands of Nepal was present in similar forms all across Nepal. It was horrible, yet a fixture.

— Ben Thapa (@DefGrappler) May 17, 2017

“My Family’s Slave” came to me at a time when I was already thinking about immigrants and the intimate, complicated relationships many of us have with this notion of worthiness in our new homes—the entrapping idea of the “model immigrant”. The narratives that colour and contour our identities in Canada—of being resilient, enterprising, marginalized, inspiring, vilified, grateful, and so on—are underpinned by the subtle and not-so-subtle understanding that we have to constantly prove why we belong here. Our Canadian passports may feel solid to the touch, but they can also feel conditional and notional—even if you were born here.

And so, of course, it makes sense then that we are always trying to scrub clean the parts of us that we deem unsightly, and buff up our exceptionalism as much as we can. This is reflected early on in Tizon’s essay:

“To our American neighbours, we were model immigrants, a poster family. They told us so. My father had a law degree, my mother was on her way to becoming a doctor, and my siblings and I got good grades and always said ‘please’ and ‘thank you.’ We never talked about Lola. Our secret went to the core of who we were and, at least for us kids, who we wanted to be.”

That sheen only goes so far though. And as Tizon’s essay and the reactions it provoked have shown, there is an important, necessary conversation to be had about the lives of those who work for us, whose names we barely remember now even if we only called them by their nicknames, who raised us, and who continue to raise us. By confronting these secrets we think we’ve left behind—or in Tizon’s case, actually living with him and serving his family in various parts of the United States—we can participate even more firmly in discussions around poverty, class, racism, justice, and dignity. These are issues that arise and intersect as we talk about immigrants in Canada. Many of us, whether a skilled immigrant or a refugee, can come from privileged perches. But once here in Canada, we usually situate ourselves on the oppressed end.

We, after all, are the ones who made it. We process the traumas of displacement and cope with survivor’s guilt by various means, and one them may be to pretend that we don’t have demons of our own to reckon with when it comes to our connections with those who worked beneath us.

To a Canadian born here, the ethical dilemma about being a part of inhumane labour practices may start with fussing (momentarily) over buying a pair of sneakers made by sweatshop workers. For some us though, those sweatshop kids were a stark, pulsating presence in our lives back home. Some of them even lived with us.

Ultimately, the act of speaking honestly and compassionately about people like Eudocia Tomas Pulido humanizes the immigrant experience and narrative. We are complex. We have secrets. Just like anyone else.

The uncomfortable realities of domestic servants don’t just operate within the purview of recent immigrants, nor is it only subsumed by the distant hum of cities in faraway home countries. Pulido’s compatriots, from the Philippines and beyond, continue to be abused here in Canada, by Canadians, under the legal sanction of the federal government’s temporary foreign worker program. It was only eight years ago that Ruby Dhalla, then a Liberal MP from Brampton and herself a child of immigrants from India, was embroiled in a national scandal after the nannies that she hired to take care of her mother accused her family of mistreatment. The caregivers were hired under the temporary foreign worker program. They were from the Philippines.

In writing this piece, I’m aware of the fact that most of the voices that I came across, critical or not, were from those who were a class above or removed from the servants. It is important, then, to acknowledge the privileges I represent and exercise, and the ways in which I am complicit in perpetuating this imbalance of power—even if only written in this case, even if only temporarily when I visit my family back home or when I travel to places where it’s normal to see underage boys serving you tea.

I hear the voices that try to normalize these realities—of the dirt-poor conditions that the servants come from, and the indignities they have to accept as a consequence of colonialism, capitalism, traditional hierarchies, and the arbitrary distribution of dumb luck that allows some of us to hire drivers to drop our kids off to their tennis lessons and some of us to drive a car so that we can feed our kids.

In spite of that yawning chasm, the lives of the servants and their masters become enmeshed with each others’, no matter how hard we try to ignore or dismiss these tenuous threads that hold whole houses and communities together.

I am reminded, above all, of the poem by Waharu Sonawane, a Bhil Adivasi activist and poet from India:

We didn’t go to the stage,

nor were we called.

With a wave of the hand

we were shown our place.

There we sat

and were congratulated,

and “they”, standing on the stage,

kept on telling us of our sorrows.

Our sorrows remained ours,

they never became theirs. […]

With “My Family’s Slave”, Tizon has attempted to own this part of his immigrant story, and share his relationship with a woman who raised him and who he ultimately considered enslaved for much of her life. In doing so, the two of them have invited confessions, revelations, and reflections from those who are connected to worlds spanning diasporas, continents, and generations.

Stories like Pulido’s show us that dignity is a delicate matter. But its reserve is surprisingly deep.