King Ralph’s parting shots

From the archives: On the eve of his retirement in 2006, the Alberta premier told Maclean’s what he really thought

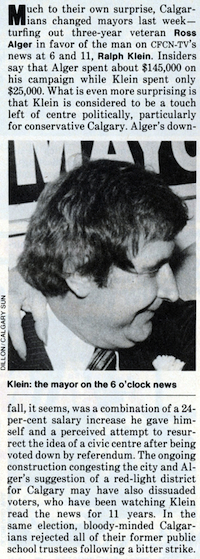

Former Alberta premier Ralph Klein in Edmonton on August 30, 2007. Six years after leaving public office, the man simply known as “Ralph” to most Albertans has been named an officer of the Order of Canada. THE CANADIAN PRESS/John Ulan

Share

Originally published September 19, 2006:

Ralph Klein — outgoing premier of the money machine that is Alberta — is sitting in his sprawling legislative office this late August afternoon, looking at once bemused, puzzled and disengaged. He has just warmed the seat for the second-to-last Question Period he will ever need to endure, in an Edmonton legislature he’s never much liked. The tone of the opposition questions — outrage both real and imagined — is the stuff of any democratic chamber in the land. But that’s where the similarity ends.

Alberta is burdened with prosperity and drowning in cash. The only debt-free province, it will have $26 billion stuffed into various savings and endowment funds by the end of this fiscal year. It has one-tenth the country’s population, yet it piled up a surplus last year larger than the federal government’s, even after paying every Albertan $400 in “Ralph Bucks.” Well, you’ve got to do something with the filthy stuff: lucre is choking the streets, clogging the drains, and clouding the mind. Half the province is being rebuilt on a grander scale. The other half would be too if not for the darned labour shortage. It’s a crisis, say Klein’s critics — the sort of crisis any other leader in North America would kill for. And yet, prosperity has been King Ralph’s undoing. He heaves a sigh: “Isn’t it strange?”

Related links:

Well, it is strange, if not quite that simple. This week, Klein will deliver to the Conservative party of Alberta a letter announcing his intention to resign as both premier and the MLA for Calgary-Elbow once a new leader is chosen by the end of the year. Many of the nine declared candidates for the job have been circling Klein for years, waiting for the first hint of vulnerability. That came in 2004, when, during the sleepwalk to his fourth election victory as premier, Klein admitted it was his last campaign. He’d intended to leave by 2008, but he underestimated both the dissatisfaction in the party with his laissez-faire leadership, and the hunger of his rivals, once lame duck was on the legislative menu. The result was a tepid 55.4 per cent support at the party convention this spring. His friend, Peter Elzinga, interim executive director of the party, gave Klein the vote result minutes before it was announced on the convention floor. “It broke my heart for the man, it wasn’t a pleasant task,” Elzinga says. “He said, ‘Well, Peter, I guess that means I’ll just push up the time period in which I leave.’ ”

In fact, Klein was crushed. His wife, Colleen, perhaps the country’s most influential and iron-willed political spouse, called the vote “dirty politics at its best.” Even today, Klein admits, the vote result hurts. “But having had time to give it some thought, I believe the delegates voted not so much against me but against the time I had allowed myself to wind my affairs down as premier.” Certainly that’s what he took from a spring and summer farewell tour as he golfed and barbecued his way through small town and rural Alberta. He still wows ’em in Eaglesham, High Level and Taber. “Take a bow Ralph Klein,” said the Medicine Hat News during an August visit. “This human persona he speaks of,” gushed the news story, “reminds all that he is one of the people working for the people and not above the people.” It’s the kind of unconditional love he’s never had in the Alberta capital. He arrived as the rumpled, rum-soaked ex-mayor of Calgary. He leaves clinging to the illusion of his status as an outsider. “My sense is that there is tremendous support and that feels good,” he says, adding with a hint of bitterness, “except in Edmonton.”

The heartland is where he built his leadership base in 1989 as an ambitious new environment minister, accepting invitations to every bun-toss, cheque presentation and ribbon-cutting he could find. His innate ability to soak up the public mood, distill it and communicate it in simple terms had already made him a success as a television reporter, and then a star as Calgary mayor, says Rod Love, an adviser, friend and enforcer. Love had signed on in 1980 as political fixer to Klein’s first run for mayor. “It was chaos,” he recalls. Still, he says Klein had sussed out the public mood of a city then in a boom cycle — “that nobody is telling us what’s going on in our city, change is coming too fast.”

That ability to read the winds served him well, particularly in pursuit of his singular achievement as premier — eliminating the deficit and debt. “There never was this right-wing madman at the controls in the premier’s office,” says Love. “There’s a guy who proposed to Albertans that we start to run our public affairs the way we run our private affairs.” It was the first “common sense revolution” in all but name, says former Ontario premier Mike Harris, whose own cuts followed more than two years later. “He was the first in Canada in my view, federally or provincially, to start talking in a common sense way about deficits, deficit financing and paying your own way, providing a climate for free enterprise to thrive and recognizing limitations to government’s role.”

It was, strangely, with the bills paid and the money flooding in, that many think Klein’s radar failed him. Debt-busting was a clear, achievable goal, with broad general support. But it also created a backlog of needed infrastructure projects, compounded by the equivalent each year of a mid-sized city drawn to the province by the red-hot economy. People don’t bring their schools and hospitals with them, Klein says. Is it harder to govern in times of prosperity than restraint? “Sometimes I think it is, during the times of deficit elimination and debt reduction, no meant no. Now,” he says, “it means maybe. Yes meant yes, and now yes still means yes, of course. And maybe means yes. And no means maybe.”

An aide describes a recent one-day parade of supplicants visiting the premier’s office, each pleading for just a sliver of Alberta’s revenue pie for one worthy project or another. The aide tallied the requests at day’s end: $800 million. Recent budgets have climbed by eight to 10 per cent annually. Fiscal hawks call it a betrayal: “You can’t say this is a fiscally conservative government,” says Scott Hennig, Alberta director of the Canadian Taxpayers Federation. “If you compare the first half of his tenure to the second half, it’s night and day.” The left calls it a “tragedy”: “Having created [prosperity], or contributed toward that opportunity, he has no sense of how to grasp it,” says New Democrat Leader Brian Mason.

Money changes everything. Had Klein been listening, he would have heard much the same fear that propelled him into the mayor’s chair: change is coming too fast. “I don’t think I’m being unfair in saying discipline has not been the hallmark of the last couple of years,” says Love, who now volunteers for one-time finance minister Jim Dinning, the front-runner for the leadership. “I don’t want to speak ill of the current government, but there has been a drift.” Love says Klein was warned before the convention that the party was restless. “He, I guess, wanted to test that reservoir of goodwill one more time,” says Love. “And, you know, nobody wants to see Babe Ruth up there hittin’ singles.”

Somewhere along the way, the fun leaked out of this for Klein. Even after his third election win in March 2001 — the night a well-lubricated Klein hollered “Welcome to Ralph’s World” during his victory speech — some doubted the fire in his belly. Later that year, Klein tearfully swore off drink after getting into a drunken late-night altercation with a working man in a homeless shelter. Sobriety didn’t much improve his mood. This March, he threw a Liberal health policy booklet at the 17-year-old female legislative page who’d delivered it from the opposition benches. He apologized, as he always does, and was forgiven as he always is. “If you screw up, then admit it, own up to it,” says Klein. “It’s the best way because you take a huge load off your shoulders.” Mike Harris adds: “Of all the politicians I have known, including me, Ralph was the quickest to acknowledge mistakes. It ain’t easy, your natural tendency is to defend.”

Still, even in Ralph’s World, patience wears thin. Among the disillusioned is Alberta journalist Frank Dabbs, author of Ralph Klein: A Maverick Life, written in the mid-1990s. Klein is no longer the pragmatist, says Dabbs, the outsider determined to shake things up. In reality, “he is The Insider,” he says. “What has happened during the years he’s been in office is this transition from basically a one-party state to something not quite a democracy anymore.” All government information flows through his office. Habitual budget surpluses are spent with little legislative oversight. Standing policy committees are Tory-only caucus affairs, without opposition membership, or even the right to attend in many cases. “Ottawa is far more open and far more accountable than the provincial government in Alberta,” says Liberal official Opposition Leader Kevin Taft. “That’s true whether we’re talking about the auditor general, the public accounts committee, the use of government aircraft, freedom of information legislation, [lack of] all-party committees, the lobbyist registry.”

Taft accuses Klein of running on “autopilot.” Since stepping up his departure, he’s travelled to Montana, spent $69,000 on a “mission” to France and Ukraine, with an agenda so light it floated off the page, and visited Washington to promote energy exports. A trip to China was cancelled amid howls of outrage. In the legislature, Klein listed the many Alberta towns he visited this summer (usually tied to a charity golf game). “And France . . . and the casino,” a Liberal MLA heckled, in a stab at his well-known penchant for gambling. Klein ignored the insult.

For all their frustrations, both Taft and Mason of the New Democrats can only marvel at Klein’s continuing hold on the public’s affection, which endures not only in spite of his foibles, frailties and mistakes, but because of them. “He is,” Taft concedes, “the colossus of Alberta politics.” The colossus sits this afternoon in an office stuffed with 26 years of political memories: model planes and boats, hats, plaques, photos and paintings of Indian chiefs. He insists his last days have not been spent in a dither. He’s established an innovation fund to foster research in alternate energy sources from coal-bed methane to solar. There’s $3 billion set aside to make Alberta a leader in post-secondary education, and a $500-million endowment for cancer research. Where his successors will take Alberta in future years, he can’t possibly know. It will be within Canada, he believes, though there are a few who advocate otherwise. It will have more muscular and clearly defined powers, he hopes.

Klein has already given five priorities to Stephen Harper, who is not only Prime Minister but the MP for his Calgary riding. He lists them on the meaty fingers of one hand. Gun control: “Get rid of it, it’s goofy.” Kill the Kyoto Protocol: “Let us design our own devices to address global warming, in that we are a resource-based, carbon-fuel based economy.” Same-sex marriage: “That is an irksome one. Fine, I have a lot of homosexual friends, but honour the constitution of marriage.” Senate: “For God’s sake reform it. Elect it.” Eliminate the Canadian Wheat Board: “Let our farmers compete fairly relative to the sale of their wheat and barley.” Address these, he asked Harper, “because they’re goofy, Liberal, socialist issues.”

Talk turns to some of the leaders he’s outlasted in 14 years as premier. There’s Harris, of course, his first fiscal ally and occasional golfing buddy. There’s Jean Chrétien, another seat-of-the-pants populist. “Had he been prime minister 20 years ago, I might have been a Liberal.” Paul Martin? “Paul was sincere but he was too structured. He wasn’t loose enough. I think he counted on the advice of his senior officials too much.” Bob Rae, former Ontario premier and current Liberal leadership candidate? “He is, what do you call those socialists? Silver spoon? Champagne socialists, that’s it.” Lucien Bouchard? “I have fond memories of Lucien,” he says. “He was very protective of Quebec culture and the uniqueness, you might say, of Quebec. He always made sure that there was an asterisk or a note that Quebec didn’t sign on to any deal with the federal government, but he did participate on provincial matters with the other provinces. I found when he lost his leg he had a certain amount of courage. My wife and his wife used to get along well.”

He considers this list of retirees, not sure what post-political life holds for him. While he obliterated the lucrative MLA pension plan in his first sweep of cost cutting, he’ll walk away with about $647,000 in severance pay, and possibly, it’s been rumoured, a further reward from the party. “I don’t know what I’ll get from the party,” Klein says. “They can surprise me if they want.” Will he resume social drinking? “Maybe,” he says. “Maybe. Who knows?” He’ll live in Calgary, of course, and sell his condo in Edmonton. He’ll work for three public policy think tanks: the Fraser Institute, the(Preston)Manning Centre for Building Democracy, and the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington. He’ll meet with the ethics commissioner before considering a few private sector offers, he says.

Oh, and he’ll finish the communications degree he’s been picking at through the distance education program at Athabaska University. He’s got about four courses left. “I kind of like it, it’s like a mortgage, you feel lonesome without one.” He walks over to the pile of course books on his desk. He picks up a 301 level text: Communications Theory and Analysis. It’s heavy on the theory, dissecting Aristotle’s three paths of persuasion: ethos, pathos and logos. “You know,” he says, “ethics, passion and logic.” He shakes his head. “It bears no resemblance to the realities of communication,” he says. “I would hate to tell my professor that.”

He’s still chortling as the interview ends. Aristotle, what does he know about Alberta?