Uncovering a killer: Addict, drifter, walking contradiction

How Michael Zehaf-Bibeau’s life spiralled from privilege to petty crime and drugs to, eventually, deadly extremism. The story of a desperate madman.

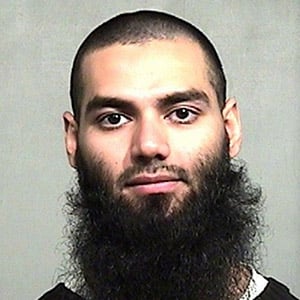

Michael Zehaf Bibeau is shown in this Twitter photo posted by @ArmedResearch, which said in a Tweet it came from an Islamic State media account. RCMP said at a news conference Thursday, Oct. 23 that police are attempting to identify the source of the photo and don???t know who took it. RCMP also said Zehaf Bibeau, killed after a deadly shooting at the National War Memorial and on Parliament Hill, was not on the RCMP’s watch list of potential high-risk travellers.

Share

I.

IN THE FALL OF 2011, three years before the nation knew his name, Michael Zehaf-Bibeau was living in British Columbia’s Lower Mainland, puffing on crack pipes and praying for redemption. Twenty-nine at the time, he was both a volatile junkie and a devout Muslim, forever hopeful that his faith in Allah would help him—someday—crush the drugs and the demons. He worshipped at a Burnaby mosque, Masjid Al-Salaam, on a street called Canada Way.

Boasting an education wing with classrooms and a library, the mosque’s mission is to enlighten “both Muslims and non-Muslims in an attempt to counter distortions and misconceptions about Islamic beliefs and practice.” Guests of all faith are not only welcome, but routinely invited. (During the Winter Olympics, hockey games were broadcast on a big screen—for any fan who wanted to cheer.)

For the man destined to attack Canada’s capital, that type of open-door policy was borderline blasphemy. “He had a problem with this,” says Aasim Rashid of the B.C. Muslim Association, which oversees the mosque. “He told the administration: ‘This is a mosque. This is supposed to be for Muslims. What are you doing?’ One of the officials sat him down and told him, quite forcefully: ‘This is how we operate. If that is bothersome for you, maybe this is not the right mosque for you.’ ”

Although Zehaf-Bibeau did tone down his objections, he stopped showing up soon enough—because he was in jail, yet again, the latest in a string of arrests that included convictions for fraud, theft, assault and possession of a dangerous weapon. This time, the charge was robbery.

Though it was hardly a typical holdup. Armed with only a sharp stick, Zehaf-Bibeau walked into a Vancouver McDonald’s on Dec. 16, 2011, demanded money from a cashier—then told a judge he was trying to get caught so he could sober up behind bars. “I’m a crack addict and at the same time I’m a religious person,” he told Madam Justice Donna Sinnew, according to a transcript released by the court. “I want to sacrifice freedom and good things for a year maybe, so when I come out I’ll appreciate things in life more and be clean.”

Unmoved, a prosecutor asked that he be released on bail pending his next court date—he shouldn’t be a burden on “overcrowded” detention cells “just because he wants to do this,” the Crown argued—but the judge disagreed. “I’m going to detain him,” she said.

“Perfect,” Zehaf-Bibeau replied.

Like so much else about his scattered life, his plan ultimately failed. After two months of clean living in pre-trial custody, Zehaf-Bibeau pleaded guilty in February 2012 to a lesser charge of uttering a threat. Free again, and with no place to live, he quickly returned to drugs—and to Al-Salaam. “He tried to sleep there,” Rashid says. “The caretaker who locks up every night would see the security system detecting someone in some part of the mosque, and he would find this guy trying to hide.” At one point, Zehaf-Bibeau somehow got his hands on a key, the last straw for mosque officials. They told him to go away and promptly changed the locks.

Like so much else about his scattered life, his plan ultimately failed. After two months of clean living in pre-trial custody, Zehaf-Bibeau pleaded guilty in February 2012 to a lesser charge of uttering a threat. Free again, and with no place to live, he quickly returned to drugs—and to Al-Salaam. “He tried to sleep there,” Rashid says. “The caretaker who locks up every night would see the security system detecting someone in some part of the mosque, and he would find this guy trying to hide.” At one point, Zehaf-Bibeau somehow got his hands on a key, the last straw for mosque officials. They told him to go away and promptly changed the locks.

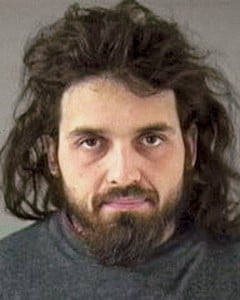

Two years later, in July 2014, the RCMP issued an arrest warrant for another man with ties to the Burnaby mosque: Hasibullah Yusufzai, a 25-year-old accused of joining a terrorist group in Syria, where Islamic State militants, also known as ISIS, have wiped out civilians and beheaded aid workers and journalists in a heinous campaign that has sparked international retaliation, including CF-18s from Canada. Of all the “foreign fighters” who have gone overseas to link up with extremist groups—approximately 130, according to the country’s spy agency—Yusufzai is the only one, to date, who faces a criminal charge. (A wanted man, he is still at large.)

For investigators trying to piece together the motives and final movements of the Parliament Hill gunman, Hasibullah Yusufzai may provide some clues. Both men knew each other from the Burnaby mosque and were seen speaking on numerous occasions. At a news conference Oct. 23—one day after Cpl. Nathan Cirillo was shot dead while standing guard at the National War Memorial—RCMP Commissioner Bob Paulson also revealed that the shooter’s email was found on a hard drive belonging to a suspect already charged with terror-related offences; Paulson didn’t say who the drive belonged to, but because Yusufzai is the only “traveller” charged so far the answer appears obvious. (Citing U.S. sources, CNN also reported a link between Yusufzai and Zehaf-Bibeau.)

Even the gunman’s mother, in one of two written statements sent to news outlets since the attack, said her son spoke about an accused terrorist “mentioned in the media” and that “he had met him in the mosque.”

In the end, the Burnaby connection may be overblown; as improbable as it sounds, it could be mere coincidence that a man wanted for terrorism had the email address of an eventual terrorist. (Dave Bathurst, who attended the mosque with both men, told Maclean’s that Zehaf-Bibeau had already been kicked out of Al-Salaam by the time Yusufzai started down his path of radicalization, and doesn’t believe they were anything more than minor acquaintances.) But as details continue to trickle out, day by day, one thing appears certain: at some point, Michael Zehaf-Bibeau was swept up by the same toxic, Islamist rhetoric that allegedly convinced his old acquaintance to join the jihad in Syria. And when the 32-year-old was unable to secure a passport, he chose instead to wage a one-man war in downtown Ottawa.

Zehaf-Bibeau was many things. Addict. Drifter. Walking contradiction. In one of her written statements, Susan Bibeau said she doesn’t believe her estranged son was driven by a “grand ideology,” and what he did on Oct. 22 was rather “the last desperate act of a person not well in his mind.” In her opinion, “mental illness is at the centre of this tragedy.” But within hours of her comments hitting the Internet, the RCMP released its own written statement about the “terrorist attack,” saying investigators have “identified persuasive evidence” that Zehaf-Bibeau was indeed “driven by ideological and political motives”—including a videotaped message from the gunman himself, citing his religious views and criticizing Canada’s foreign policy.

“He was quite deliberate, he was quite lucid and he was quite purposeful in articulating the basis for his actions,” Comm. Paulson told reporters, adding that in the recording, still unreleased, the killer specifically refers to Allah.

Was he mentally ill? Had years of hard drug abuse so clouded his twisted mind that he considered it his religious duty to murder an unarmed soldier? At what specific point did he cross the line, determined to kill?

“He said he has to fight the injustice of foreign intervention in Muslim regions,” says Paul Jarjapka, who met Zehaf-Bibeau six weeks before he opened fire. “This guy was not a raving lunatic. He was reasonably intelligent, he was articulate, and he wasn’t the kind of guy who sounded like an idiot or babbled on. His viewpoints were extreme—some I’d call insane—but he knew how to argue his point.”

By that point, Zehaf-Bibeau was living at The Beacon, a Salvation Army shelter in downtown Vancouver—feeding his crack habit one minute, kneeling on a prayer mat the next. In the mornings, he would watch the news with fellow residents, and passionately defend the latest atrocity unleashed by Islamic State fighters in Syria and Iraq.

“His argument was that we live a decadent and immoral lifestyle, that we live Godlessly, and that we must be taught a lesson and punished,” says Jarjapka, a fellow shelter resident who engaged in numerous heated debates with the long-haired man who would soon be infamous. “I looked at what he said to mean God will punish us in the end, that type of thing. I had no idea this guy was going to go ahead and try to initiate his own punishment.”

II.

MICHAEL ZEHAF-BIBEAU entered the world as Joseph Paul Michael Bibeau on Oct. 16, 1982, the product of an at-times topsy-turvy relationship between his Canadian mother, Susan Bibeau, and his Libyan father, Bulgasem Zehaf. They split up before Michael was born, and Susan chose to keep Zehaf’s name off the baby’s birth certificate. The two eventually reconciled during their son’s early years, and married in 1989; six years later, when Michael was 13, his parents applied to legally change his name to reflect his father’s parentage: Joseph Paul Michael Abdallah Bulgasem Zehaf-Bibeau. “I was entitled to take care of my son, to look after his education, his security and give him all my love,” his dad wrote in supporting court records obtained by Maclean’s.

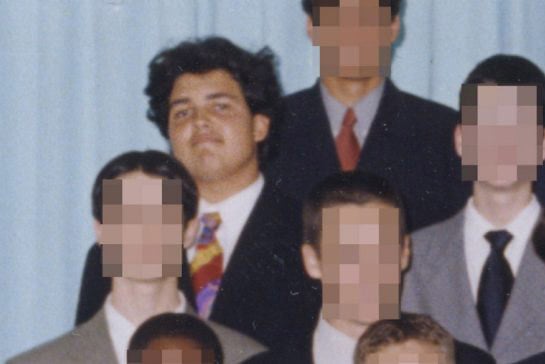

The family of three lived in relative middle-class obscurity in the Montreal suburb of Laval, in a modest detached home. In eighth grade, Zehaf-Bibeau attended Collège Stanislas, a primary and secondary school in the swanky Montreal redoubt of Outremont. He switched to Collège Laval the following year, and was remembered by classmates as a fun-loving, mildly goofy kid—and someone who, like many of his peers, dabbled in soft drugs. (Although Zehaf-Bibeau was not raised as a Muslim, some say his father, though hardly pious, did fast during Ramadan, and his embrace of Islam later in life was as much a conversion as a reconnection with a faith he knew as a child.)

By the time Zehaf-Bibeau finished high school, his parents’ relationship was teetering. A lawyer, Susan (pictured, right) had steadily climbed the federal bureaucratic ladder, having served as a refugee protection officer and legal adviser at the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB), the independent tribunal that decides, among other things, who warrants asylum in Canada. Zehaf—“Bello” to his friends—had found his own success in Montreal’s roiling nightclub scene, opening two boîtes de nuit on Crescent Street in the city’s downtown. Although reports have said the couple divorced in 1999, Susan Bibeau continues to refer to Bulgasem Zehaf as her husband.

In any case, 1999 was a pivotal year for their son. He graduated from Saint-Maxime, a public school, and with his parents working so much he often had the house to himself. Loud, late parties were a regular occurrence. “He likes to laugh and his smile drives girls crazy,” said his final yearbook inscription. “He’ll go far in life.”

He didn’t. Instead, his life spiralled down a path of drugs and crime. Beginning in 2001, at 19, he racked up a formidable number of convictions in Montreal, including assault and battery, weapons possession and drunk driving. In 2004, he served a 60-day sentence for possession of PCP, a potent hallucinogenic drug. Numerous people who knew Zehaf-Bibeau say he could be obsessively paranoid, convinced that the shaytan, the Islamic term for devil, was constantly trying to tempt him. “I remember him telling me that he had a long history of the devil chasing him,” Dave Bathurst says. “He was concerned that the devil was trying to get at him through other people.”

As her son struggled with his obvious inner demons, Susan Bibeau’s career continued to flourish. In 2005, she became immigration-division director for Quebec and the Altantic provinces, and in 2009 she was appointed director-general of her division—the same year her relationship with her son fell apart. He moved to B.C., 4,900 km away, and more than five years would pass before Bibeau spoke to him again.

A Muslim convert, Bathurst first met Zehaf-Bibeau at Masjid Al-Salaam during Ramadan in 2010, but it wasn’t until the following year, when Bathurst and his wife moved to Burnaby, that he saw him on a regular basis. Some days, Bathurst gave him a ride home after prayers. “He told me that he completely cut ties with his family and, somehow, he felt wronged by them,” he recalls. “He said he basically told them that he didn’t ever want to talk to them again.”

Bathurst operates a Vancouver-area landscaping and irrigation company with his father, John, and he offered Zehaf-Bibeau some work in 2011, digging holes for sprinkler systems. Although he lasted only two days on the job (Bathurst can’t recall why), Zehaf-Bibeau appeared relatively stable. He rented a bedroom in a house and, later that fall, Bathurst helped him move his few belongings to a basement suite in Burnaby.

By that November, though, Zehaf-Bibeau was once again a slave to substances—crack cocaine, in particular. What little cash he had was feeding his habit. “I remember him calling me and asking me to lend him money,” Bathurst says. “There was one time I actually gave him money, and then I thought: ‘This is textbook, typical drug-use behaviour.’ I never loaned him money again.”

On Dec. 15, 2011—unable to pay his rent and living on the street—Zehaf-Bibeau walked into a Burnaby RCMP detachment and confessed to a 10-year-old armed robbery he supposedly committed back home in Montreal. He told the constable at the front desk he was desperate to get arrested so he could receive help for his addiction. The officer couldn’t find any record of the robbery, but was concerned enough about the visitor’s mental state that he did send him to a hospital.

Related:

Glenn Greenwald on what Canada should not do now

Lone-wolf attacks and the future of terror

Two killers, one twisted objective

Interactive timeline: What happened in Ottawa

According to court records, Zehaf-Bibeau was seen by a psychiatrist that night, but released “in short order” because the doctor concluded that “he didn’t suffer from a mental illness.” Early the next morning, he walked into that downtown McDonald’s, stick in hand, and told the “homeboy” behind the counter to “hand over the money.” When the cashier phoned 911, Zehaf-Bibeau stepped outside and waited for the cops. “I warned them, ‘If you can’t keep me in, I’m going to do something right now, just to be put in,’ ” he told the judge. “So I went to do another robbery, just so I could come to jail.”

Zehaf-Bibeau was ordered to undergo another psych assessment, his second that week, but the conclusion was the same: Although his decision to choose jail over bail was “unusual,” he displayed no “features or signs of mental illness” and “is presumed fit to stand trial.”

In February 2012, after 66 days in pretrial custody, he agreed to plead guilty to the lesser charge of uttering a threat. Before the hearing, though, he was examined a third time, this time by Jack Bibby, a court liaison officer with B.C.’s forensic services commission. “Mr. Bibby feels he has undiagnosed mood disorder, so something along the lines of bipolar,” said the prosecutor, Mark Gervin. “According to Mr. Bibby, he’s like many people on the street who are suffering, probably, from undiagnosed mental health issues.”

Zehaf-Bibeau didn’t utter a word during the sentencing hearing, but he did tell Bibby he disagreed with the bipolar diagnosis. His lawyer, Brian Anderson, even described his client as a “perfectly functioning individual” whose crime was motivated solely by a desire to go to jail and kick his crack habit. “He seems to have done that,” Anderson said.

“Good luck to you, sir,” the judge said.

By that point, luck wouldn’t be nearly enough to keep him on track. When he returned to the Burnaby mosque, Zehaf-Bibeau appeared to be a changed man—at first. He told Bathurst he filled his days in jail reading the Quran and kicking his addiction (“a life-changing experience”) but it wasn’t long before he reverted to his paranoid ways, telling people “the devil was after him again.” When mosque officials caught him with the key and kicked him out, they were convinced Zehaf-Bibeau was back on drugs. “We don’t know where he stole the key from, or how he got it,” says Rashid, of the B.C. Muslim Association. “That was the last we heard of this guy.”

As for the potentially nefarious connection between Zehaf-Bibeau and Yusufzai, both Bathurst and Rashid have their doubts. Although Rashid says Yusufzai was asked to leave the mosque after expressing alarmingly extremist opinions, Zehaf-Bibeau never exhibited any such signs; he was booted because he stole a key, not because he talked about supporting armed jihad. “I’m concerned about labeling communities and trying to find terror cells where they don’t exist,” Rashid says. “There is over-speculation about the mosque. The mosque is not what radicalized them, nor did it provide facilities for such a thing.”

Bathurst confirms that Yusufzai (pictured, left) and Zehaf-Bibeau did interact at Al-Salaam, but says their discussions would have occurred well before Yusufzai starting expressing extremist beliefs. “When Hasib knew Michael he was a really different person,” Bathurst says. “During that time, Hasib was a really nice guy, very generous guy, really compassionate human being.” And if they did exchange emails, as the evidence suggest, that’s not necessarily suspicious, Bathurst says. “In a church or a school setting, or wherever you’re acquainted with people, you would get their email or Facebook,” he says. “They prayed in the same place, they did talk to each other. There is no question there. But when Hasib would have known Michael, that would have been before he became more radical.”

At this point, the RCMP is still investigating any potential links to Zehaf-Bibeau, and whether others may have “contributed or facilitated in any way” to what happened on Parliament Hill. Asked about the significance of Zehaf-Bibeau’s email being discovered on another suspect’s computer, Paulson told reporters the answer still isn’t clear. “It can be the most tenuous of connections or it can be something else,” he said. “So we need to understand what that connection is.”

What is understood, without question, is that Zehaf-Bibeau was living in Alberta by 2014, earning a good wage in the oil fields and diligently saving his money. “He had access to a considerable amount of funds,” Paulson said. “We are investigating all of his disbursements in the period leading up to the attack.”

On Aug. 1, less than three months before that attack, Zehaf-Bibeau was slapped with a photo-radar speeding ticket near Edmonton. By Labour Day, he was back in Vancouver.

By chance, Bathurst ran into him that holiday weekend at a downtown prayer centre. They hadn’t spoken in more than a year. “He told me he was going to go study in Libya, and that he was basically sick of trying to fit into Canadian society,” Bathurst recalls. “I said: ‘Well, make sure that you’re specifically going to study.’ ” At the time, Bathurst wasn’t overly suspicious. Zehaf-Bibeau’s father is from Libya, he had relatives there, and he’d already visited the country, most recently in 2007. But just to be sure, he asked him—again—to clarify his intentions. “I made him eyeball me and tell me he was going there to study,” Bathurst recalls. “And he was very adamant that he was going there to study.”

III.

HE HAD VENTURED WEST for a new beginning, a chance to forget his family and salvage some kind of future. Five years later, during his last few nights in Vancouver, Zehaf-Bibeau was in the same old place: a downtown homeless shelter, scrounging for his next taste of crack cocaine. It was mid-September, less than six weeks before his suicide mission.

In the mornings, while watching the news on the shelter’s communal television, Zehaf-Bibeau was so often outraged by a particular headline that it would ignite heated arguments with fellow resident Paul Jarjapka, who was staying at The Beacon while in town for a job training program. “His position was that ISIS is fighting a war that has to be fought because the side of decadence and arrogance and debauchery that we live in is trying to overcome the strict, religious beliefs and discipline that they live,” Jarjapka says. “He said it all the time: ‘You’re either going to God or you’re going away from God. There are only two things. There is no in between.’ ”

He said Americans, not ISIS, are the true terrorists. That Islamic State’s mass murder of non-Muslims is moral and justified. That God “was speaking” to him. “We had one big argument about collateral damage,” says Jarjapka, 57. “My point was: if the United States is bombing a specific target and innocent children are killed, yes, I’m against that. I’m against innocent people being killed. But that is not the same as targeting a school bus full of women and children and blowing it up. He said: ‘No, that is the same. Those two instances are identical.’ ”

During one of their many arguments, Jarjapka told Zehaf-Bibeau that a full-blown ground war is the only way to eliminate ISIS. “He got very offended by that,” he says. “He was one of those guys you could tell was wound a little too tight and was quick to go off the handle when you confronted him on his views, but I didn’t really see him as a mental health case. I see a lot of people who are completely out there, and this guy was not that. He was not a guy who had a major mental health issue and didn’t know what the heck he was doing. He knew what he was doing.”

At the time, Jarjapka had no inkling he was arguing with a future killer. Zehaf-Bibeau seemed like a big talker, nothing more. “He was always beefing about his passport, that he wanted to get overseas,” Jarjapka says. “He didn’t say he was going to Syria, and he didn’t say he was going any place in particular. But he wanted to leave here.”

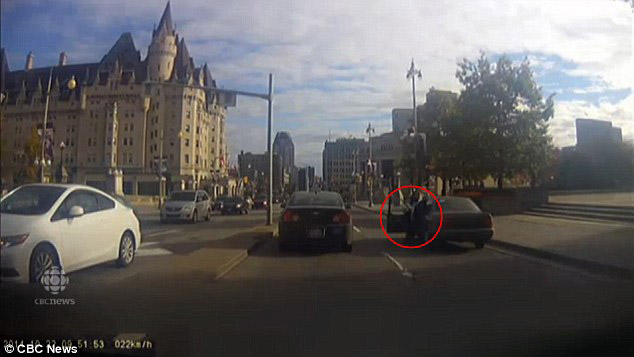

He checked out of the shelter around Sept. 20—four weeks before pulling up to Parliament Hill, scarf over face—determined to hitchhike back east and iron out his passport problem. Investigators are still trying to piece together that final month of his life, hoping to pinpoint exactly when he hatched his plot. But the details disclosed so far suggest the plan came together in rapid fire, and that his elusive passport was likely the final straw.

Related:

The moment for hugging is over: It’s time to debate policing powers

RCMP says Ottawa shooting driven by ideological motives

Mother of Michael Zehaf-Bibeau: ‘We are so sorry’

Life during wartime: We’re all witnesses to war

In Ottawa by Oct. 2, Zehaf-Bibeau visited the Libyan embassy, hoping to renew an expired passport issued by that country when he visited his father’s homeland in 2007. His bizarre demeanour and confusing answers raised enough red flags that an embassy official told him it would take at least three weeks to assess his request. He walked out instead. By then, his Canadian passport application was still being processed, but unbeknownst to him, the file had been forwarded to the RCMP for a criminal background check, causing even more delay.

On Oct. 16, six days before he shot Cpl. Cirillo, Zehaf-Bibeau turned 32. By then, he was sleeping on the second floor of yet another homeless shelter, the Ottawa Mission, a 20-minute walk from the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. He woke every morning before sunrise to pray, kneeling in a hallway outside his room. Some residents say he was confrontational, boasting about hating Canada and being on a no-fly list. Others say he looked like so many who come through the door: lost, lonely and in search of something. “He was just another guy,” said one resident, himself a recovering addict who declined to give his name. “He just looked like your average person you see in these places.”

At some point, Zehaf-Bibeau sent an email to his mother—their first communication in more than five years—saying it was his religious duty to be good to his parents. They met for lunch. In her lengthy statement to Postmedia, Susan Bibeau said her son talked mostly about religion, how she “was wrong to pursue the materiality of this world,” and that his plan was to move to Saudi Arabia, an Islamic country where he could study the Quran and where people “would share his beliefs.” As he so often said before, Zehaf-Bibeau also told his mom the shaytan was testing him. “This was not new,” she wrote.

Back at the shelter, residents heard him yelling into a payphone, desperately trying to rent a vehicle; unsuccessful, he turned his attention to used-car ads. On Oct. 21, the morning before his attack, he purchased a used Toyota Corolla for $650. Numerous reports say he negotiated $50 off the $700 asking price—and before handing over the cash, he asked the seller if he could simply borrow the car for a day and then bring it back.

That same Tuesday, he drove the Corolla 150 km to an aunt’s home in Mont Tremblant, Que. Years ago, Zehaf-Bibeau lived at the house for a while, but a decade had passed since he’d been there. He ate dinner with his aunt and reminisced about old times, and then spent the night.

The RCMP now says that when Zehaf-Bibeau climbed back into his Corolla the next morning, he brought along a knife he had stored on the property years before. The Mounties are still sorting out whether his rifle, a lever-action .30-30 Winchester, came from the same place. “It is an old and uncommon gun,” Comm. Paulson said. “We suspect that he could have similarly hidden the gun on the property but our inquiries continue.”

When, or where, Zehaf-Bibeau recorded his final manifesto still isn’t clear. But as he drove the 90 minutes back to Ottawa that Wednesday morning—Oct. 22—he made the journey without any licence plates on his Corolla. Tragically, nobody pulled him over.

As the clock in his car approached 9:50 a.m., Zehaf-Bibeau steered toward the National War Memorial, Cpl. Cirillo oblivious to the imminent danger approaching from behind.

Like millions of other Canadians, Paul Jarjapka saw the gunman’s face on the news. “I walked into the TV room and I saw the picture, the one of his covered face with his eyes showing,” he recalls. “And I said: ‘Wow, that looks just like that Mike guy.’ The guy beside me said: ‘It is that Mike guy.’ ”

IV.

SO MANY QUESTIONS LINGER. Where did Zehaf-Bibeau get the rifle? What pushed him over the edge? Was he inspired by recent dispatches from Islamic State, urging Westerners—Canadians included—to strike at home if they can’t join the fight overseas? Or was he a copycat, following in the “lone wolf” footsteps of Martin Couture-Rouleau, another radicalized Canadian who, less than 48 hours earlier, ran over two soldiers with his car in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Que., killing Warrant Officer Patrice Vincent?

Paulson said police “have no information linking the two attacks,” and that all signs suggest Zehaf-Bibeau acted alone. But the RCMP commissioner did tell reporters that the gunman, like Couture-Rouleau, had hopes of travelling to Syria, suggesting his desire to join Islamic State. “His mother told us that,” he said.

But Susan Bibeau didn’t say that. She specifically told police—after her son opened fire—that he wanted to go to Saudi Arabia, not war-ravaged Syria. “Most will call my son a terrorist,” she wrote. “I don’t believe he was part of an organization or acted on behalf of some grand ideology or for a political motive. I believe he acted in despair.”

“Was he crazy?” her letter continued. “I never could have imagined that he would do something like this, but he was not well, either.”

Dave Bathurst also suspects that his former acquaintance was mentally unstable. When he knew him, Zehaf-Bibeau never once expressed any extremist or violent tendencies. “I honestly think, with him, he had given up hope and that’s why he did it,” he says. “I never saw him being capable of what he did—absolutely not.”

Daud Ismail, the chairperson of the al-Salaam Mosque, broke into tears on the day of the attack after a Maclean’s reporter told him the gunman once worshipped there. “All I can say to the Canadian public is I’m bleeding in my heart,” he said, his voice cracking. “As far as our mosque is concerned, we have zero tolerance. Police should go after people like this and they should be prosecuted to the full extent of the law.”

Few would disagree. But as the RCMP continues their investigation, other questions remain: Could Zehaf-Bibeau have been stopped before he ambushed Cpl. Cirillo? Should he have been? Did the national-security apparatus built to protect Canadians fail to pick up signs of a looming threat? Those answers are hardly so simple, despite what hindsight might suggest.

On Oct. 8, exactly two weeks before the attack, Paulson and Michel Coulombe, the director of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), appeared before a House of Commons public safety committee to discuss the very type of threat about to engulf Parliament Hill. They told the country that 130 people have left Canada to join overseas terrorist groups (including approximately 30 who have linked up with Islamic State) and that another 80 are safely back home. “Yes, we know where they are,” Coulombe said, reassuringly. In the meantime, Paulson revealed that the RCMP has 63 active national-security criminal investigations targeting 90 individuals (now 93) “who are related to the travelling group: both people who intend to go, or people who have returned and have been referred to us” by CSIS.

On Oct. 8, exactly two weeks before the attack, Paulson and Michel Coulombe, the director of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), appeared before a House of Commons public safety committee to discuss the very type of threat about to engulf Parliament Hill. They told the country that 130 people have left Canada to join overseas terrorist groups (including approximately 30 who have linked up with Islamic State) and that another 80 are safely back home. “Yes, we know where they are,” Coulombe said, reassuringly. In the meantime, Paulson revealed that the RCMP has 63 active national-security criminal investigations targeting 90 individuals (now 93) “who are related to the travelling group: both people who intend to go, or people who have returned and have been referred to us” by CSIS.

One of those high-risk travellers under investigation was Couture-Rouleau, so mesmerized by Islamic State’s jihadist propaganda that he tried to join them in Syria. The RCMP arrested him at the airport, seized his passport and enlisted the help of his family to try to “de-radicalize” him. He steered his car toward two unsuspecting soldiers instead. “Even if we’d had surveillance on him in the parking lot, we probably would not have been in a position to have stopped his attack on those soldiers,” Paulson said. “That’s the kind of threat that we’re having to deal with.”

Threats like Zehaf-Bibeau are even more difficult to spot, let alone thwart. As Paulson acknowledged, the RCMP (and, presumably, CSIS) knew his name before the rest of the country did, because his email was found on that hard drive. The Mounties, Paulson said, also had “uncorroborated information” that Zehaf-Bibeau “was an individual who may have held extremist beliefs.” In other words, he was on their radar, however tenuously.

But what the authorities knew about Zehaf-Bibeau was literally one speck of intelligence among so many other snippets about so many other people. And if the RCMP doesn’t have the resources to place 24/7 surveillance on a person like Couture-Rouleau—an identified, high-risk threat under active criminal investigation—how can they possibly monitor a person like Zehaf-Bibeau, who barely registered on their radar?

“He really was just a needle in a haystack, and there is almost nothing security services can do with an individual like this,” says Lorne Dawson, a University of Waterloo professor and co-director of the Canadian Network for Research on Terrorism, Security and Society. “If there are 90 high-risk travellers they are monitoring, then they are also aware of all the people connected to those 90, which is a network of hundreds of people, potentially thousands. There just aren’t enough resources. You have to take all the individuals you’re dealing with and subject them to assessment tools to figure out who is really someone to worry about.”

Zehaf-Bibeau, it appears, was not one to worry about. “Hindsight is 20/20,” Dawson says. “So he had email contact with Yusufzai. So did God knows how many other people.”

Paulson said his force is now “sitting down with CSIS” to re-evaluate their ever-evolving targets and see if some warrant more attention. The RCMP’s national-security investigative team, once 180 officers strong, has also been bolstered with an additional 250 Mounties. “We’re moving resources from organized crime cases, from financial integrity cases, and from other important federal obligations that we have,” he said. “I think the simple answer is: it’s very labour-intensive.”

Yet as hard as they work, as many resources as they deploy, authorities will never have an absolute pulse on every potential Michael Zehaf-Bibeau. “People want simple answers—to feel safe—but the challenges are very difficult,” says Michael Zekulin, a University of Calgary professor who specializes in radicalization and anti-terrorism. “A motivated individual is very difficult to stop, even if you’re there.”

— with Martin Patriquin