Peter C. Newman: The ‘bad joke’ of our Navy

Having escaped the Nazis in his youth, Peter C. Newman wanted to prove he was a true-blue Canadian. What he found, then and now, were dramatic shortcomings

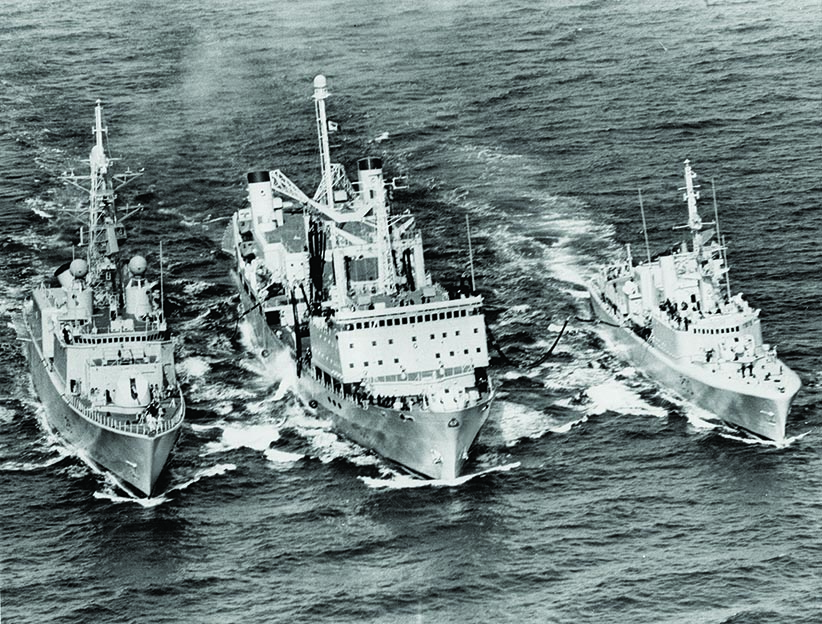

Refuelling on the run; two destroyers and a supply ship make a five-day patrol of the North Atlantic fisheries. For the navy the exercise was a welcome respite from austerity-enforced idleness. (Doug Griffin/Toronto Star/Getty Images)

Share

Our insulting approach to national defence policies has a long-standing tradition of failure to communicate in the face of opportunity. Back in the 1930s, when Calgary’s crack cavalry regiments switched from horses to tanks, it was so unprepared that its armourers had to simulate the new-fangled vehicles by using burlap-covered frames mounted on motorcycles. They, in turn, were replaced by Chevrolets clad in sheet metal. A generation later, during an army cadet training class near Fredericton that I attended, there weren’t nearly enough rifles to go around, so most of the troopers had to carry broomsticks instead. At one point, I watched a cadet point his broom at a fellow soldier, and menacingly yell: “Bang, bang, you’re dead!” To which his intended victim calmly replied, “No. I’m not. I’m a tank!” Drawing on that loosey-goosey tradition, it explains why I was not surprised by the news that the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) was down to one operational destroyer and a fleet of ancient second-hand submarines with built-in slow leaks.

I found the news hardly unexpected for another reason: Having been a member of the naval reserves since 1947, I was reminded of a long-ago interview I had with Pierre Trudeau when he was prime minister, in which he reluctantly admitted that the RCN was rated only 14th on his list of priorities. That was just behind convicts and hog-marketing boards—in other words, nowhere.

I spent nearly four decades in the naval reserves, including annual forays into strange and welcoming harbours. My naval career was based on a life plan hatched after graduating from Upper Canada College in Toronto. Having escaped the Nazis in a series of lucky escapades during my youth, I desperately wanted to prove that I was now a true-blue Canadian. The only solution my pea brain could figure out to publicize that happy fact was for me to join the Navy. Even the lowest ranks were issued sailor suits that featured shoulder flashes that plainly identified its wearers: CANADA.

I spent the balance of the summers of my teenage years and early 20s being trained in naval skills as a member of the 9,000-strong University Naval Training Division. We became a band of brothers and practised a very un-Canadian love of country that remained our guiding light for the rest of our days. That included nurturing an active naval component in our military, which was an integral part of our pledge. Our traditions dated back to the Second World War, when Canada proudly floated a 434-ship armada that was decisive in Allied victories. We never were a fighting nation, but our wartime Navy, especially guarding the trans-Atlantic convoys on which Britain’s survival depended, was monumentally successful.

Related: The Navy looks dead in the water

My first sea adventure was aboard HMCS Portage, a 900-ton Algerine bound for Bermuda. Canada’s smallest warship, she was really a converted minesweeper turned into a convoy escort. The training was relentless and the sea was cruel. As the tiny vessel started shushing down mountainous waves, aiming itself at the sea bottom, you could tell the crew stayed riveted to one thought: that this rustbucket was built by its lowest bidder–so that the open question remained: At what point would she split apart? It never happened. But when I took over the helm, the officer of the watch looked back at my wiggly wake and quipped that it reminded him of “a snake with hiccups” at the wheel.

It was when I started to consider seriously the record of Canada’s fleet-in-being that I found evidence of drastic shortcomings. Our vital naval element had turned into a bad joke. Officially listed as part of our NATO contribution, the destroyer HMCS Crusader, for example, plus half a dozen sister ships, were in such dire straits, you could walk through what were supposed to be their watertight bulkheads. The supply vessel HMCS Protecteur had an antiquated three-inch gun mounted, not for protection, but to qualify as a warship and, thus, gain preference at local fuel pumps. Both of our supply ships are now permanently out of service, and have not been replaced. Instead, the Navy brass have developed a ghost fleet of ships that are still included in our official NATO contribution. Instead, they are being regularly cannibalized for spare parts to keep us in the game. We now have a much larger collection of barely floating naval skeletons than war-ready operational vessels—and, even if we’re not really history’s first one-ship navy, it’s a handy metaphor to keep in mind when remembering that Canada is charged with defending the world’s longest coastline.