Is Omar Khadr days away from freedom?

At a bail hearing in Edmonton, the key question is not whether the infamous prisoner poses a threat

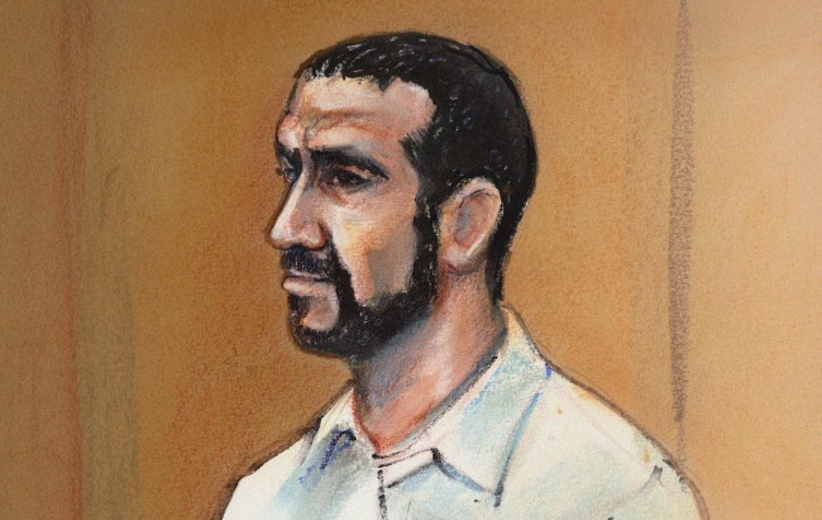

Omar Khadr

Share

Omar Khadr was late for his 10 a.m. bail hearing. For whatever reason, his Tuesday-morning ride from Bowden Institution to Edmonton’s downtown courthouse (two hours, door to door) didn’t depart the prison parking lot when it should have. By the time he finally appeared in the third-floor courtroom, sporting jeans, a white golf shirt and a neatly trimmed beard, it was 10:45.

Not that clocks have mattered much to Omar Khadr. He’s had nothing but time.

Now 28, Khadr has spent nearly 13 years—4,623 days, to be exact—as an inmate: the first decade locked inside the notorious American detention camp at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, the last chunk incarcerated in Canada. He has clearly grown accustomed to the rhythms and routine of custodial life, and as he strolled to his assigned seat (noticeably void of handcuffs or leg shackles) Khadr grinned and scanned the room. Seven uniformed sheriffs kept a close eye.

By this point, Canadians are all too familiar with his seemingly endless story. The 15-year-old son of a senior al-Qaeda associate. The 2002 firefight in Afghanistan. The grenade toss that killed a U.S. soldier. In 2010, Khadr pleaded guilty to five offences under the so-called Military Commissions Act, including the battlefield murder of Sergeant 1st Class Christopher Speer, an aspiring doctor and father of two. Key to the plea deal was a promise that Khadr could apply for a transfer to a Canadian prison, allowing him to serve the remainder of his eight-year sentence in the country of his birth.

Which brings us to today’s bail hearing. Khadr now insists that everything he confessed to in the plea agreement is fiction, and that he only agreed to sign the deal to escape Guantanamo. His legal team is also appealing his convictions at a special court in Virginia, arguing, in a nutshell, that the five offences (namely “murder in violation of the laws of war”) did not exist in 2002—and that even if Khadr did kill Sgt. Speer, it was an act of war, not a war crime. In the meantime, Khadr is asking an Edmonton judge to grant him bail and set him free while his U.S. review crawls through the system. “Mr. Khadr’s appeal hasn’t moved an inch in over a year,” Nathan Whitling, one of his lawyers, told Justice June Ross. “The timetable is very unpredictable, and we’re concerned that the appeal is not going to be over until his sentence is effectively over.” (Later, Whitling joked that “we could all be retired by the time those appeals are done.”)

Like every inmate with an active appeal, Khadr has the right to ask for release (with conditions, if necessary) until a ruling is granted, Whitling argued. “Mr. Khadr should be treated no differently than any other prisoner in Canada with respect to seeking this relief,” he told the judge. “There is no reason at all why it shouldn’t apply to Mr. Khadr.”

Behind him, a few dozen supporters sat in the gallery of Courtroom 317, some wearing orange ribbons of solidarity. Among them was Arlette Zinck, a King’s University College professor who has tutored Khadr behind bars for many years, and Patricia Edney, the wife of Khadr’s other long-time lawyer, Dennis Edney. If Khadr is granted bail, it’s the Edneys who have offered him a bedroom in their home while he readjusts to the outside world. “It is unusual for a defence lawyer to make this offer, but this is an unusual case,” Whitling said of his colleague. “I think it speaks to Mr. Khadr’s character.”

Khadr’s character, then and now, has been the focus of much debate (informed and otherwise). Those who know him best are adamant he has grown up to be a peaceful, inquisitive man who wants nothing more than a second chance. Others suspect that he continues to harbour the same violent, Islamist ideologies that propelled his father, Ahmed Said Khadr, to the front lines of Afghanistan (and to leave his 15-year-old son with terrorists, who later taught the teen to wire land mines and spy on coalition forces).

At one point, Justice Ross specifically asked about a written statement issued by Vic Toews, the public safety minister when Khadr was repatriated in 2012. In it, Toews said Khadr continues to “idealize” his fundamentalist father, that family members have “openly applauded his crimes and terrorist activities,” and that because he’s had “very little contact with Canadian society” he “will require substantial management in order to ensure safe reintegration.”

Although Whitling conceded to “concerns about his family,” he pointed out that the Khadr patriarch is long dead (he was killed in a shootout with Pakistani forces 12 years ago), and the rest of the kids live in Ontario, not Alberta. “We think he should be able to have contact with his family, such as phone calls or Skype, but he’s not going to be living with them,” Whitling said. “He is not going to live in a radicalized environment unless Mr. Edney’s house is a radicalized environment.”

Sitting in the prisoner’s box, Khadr couldn’t help but smile.

In the end, though, the bail application will not hinge on whether or not Khadr poses a threat. Although the Harper government has long maintained that he committed “heinous” crimes, the feds are opposing bail on strict points of law, not character: namely, that setting him free would violate both the plea deal and the International Transfer of Offenders Act (ITOA).

Speaking for Ottawa, federal lawyer Bruce Hughson said Canada would have never approved Khadr’s transfer request had officials known an appeal was possible. “If a person wants to appeal their sentence they stay in that country where they are convicted and see that process through,” Hughson told the judge. “What Mr. Khadr is effectively trying to do is take the best of both worlds: a transfer to Canada to serve the balance of the sentence, but get out on bail pending an appeal in the United States. And that, with all due respect, is not what was intended by the Act.”

Under that Act, Hughson said, Canada’s sole responsibility is to administer the sentence Khadr received—while still granting him the standard rights of other Canadian prisoners, such as the ability to apply for parole. But a bail application pending appeal does not coincide with the Act, Hughson said, and if granted, it could harm both Canada’s international reputation and its relationship with the U.S. “If Mr. Khadr had wished to appeal his sentence, appeal his convictions, then what he should have done was stayed and done so,” he said. “By accepting and asking for the transfer to serve his sentence, he forewent those rights. Part and parcel to that is that he serves his sentence to conclusion, whatever that is.”

“Whatever” is the key word. Khadr has a parole hearing scheduled for June, which means if his bail application fails, he could still be a free man three months from now. If the Parole Board turns that down, he’s eligible for statutory release (freedom after serving two-thirds of a sentence) in October 2016. At the very latest, Khadr will walk out of prison in the fall of 2018, when the last hour of his eight-year sentence expires.

In other words, he is going to get out. The only real question is whether that day will come very soon, or soon.

The bail hearing continues Wednesday.