‘People say there were no casualties. There are two now’

Fort McMurray mourns the loss of two people who were killed as they fled the wildfire, including the daughter of a deputy fire chief

Share

This post has been replaced with the longer edition of the obituary, which ran in our print edition.

Cranley Ryan has spent two decades dousing flames, most recently as deputy fire chief of Saprae Creek, a hamlet just east of Fort McMurray. On the afternoon of Wednesday, May 4—one day after the city’s mass exodus—his crew was assigned to the Dickinsfield district, hosing down spot fires as embers and ashes crept into the abandoned neighbourhood. Cranley had slept for an hour the night before, if that, and there was no telling when the 47-year-old would get another chance to close his eyes.

His wife and children were long gone by then, driving south toward the supposed safety of Lac La Biche.

At around 2:30 p.m., Cranley’s cellphone rang. It was Melonie Matthews-Ryan, his wife, frantic on the other end of the line. There’s been a massive car crash, she screamed. Emily and Aaron are dead.

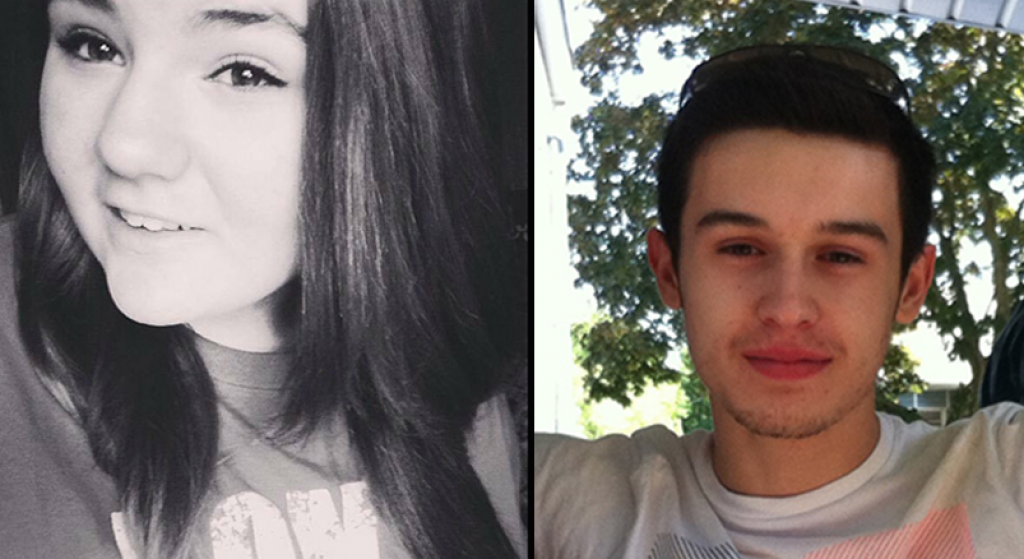

Emily was Emily Ryan, the deputy chief’s 15-year-old daughter and one-third of the family triplets. Aaron was Aaron Hodgson, Emily’s 19-year-old cousin.

“I said: ‘What do you mean Emily is dead?’ ” her father says, his voice cracking as he recalls that horrific conversation. “Melonie tried to describe what had happened, that there was an accident and a fire and she couldn’t get to them. She was hysterical.”

In a daze, Cranley told his wife he would phone her back. Then he stood near a pumper truck, draped in full protective gear, attempting to explain to his fellow firefighters what just happened 250 km away. “I was torn,” he says, “because you want to be in both places, but you can’t.” Though determined to keep battling the raging wildfire—to do his duty—Cranley needed to be with his little girl, too.

“I am a firefighter by heart,” he tells Maclean’s, speaking publicly about the accident for the first time. “I want to help people, I want to be there for them, and I would like nothing more than to be over there helping them combat this problem right now. But I had to put on my ‘Dad hat.’”

It took more than two hours for Dad to reach the crash scene, alone with his thoughts as he barrelled down Highway 881. “I was just hoping they were wrong,” he says. “I was hoping that she would be caught in the traffic behind the accident and couldn’t get up to talk to the others to tell them she was okay. It’s not that I wish that on anybody else, but I wanted it to be somebody else.”

Who wouldn’t?

When Cranley finally arrived, reality set in. The Fort Mac fire had claimed its first victims, and one of the dead was the daughter of a high-ranking firefighter. For a ravaged, heartbroken community that has already lost so much, the irony was beyond cruel.

“It’s one of those things,” says Cranley, who has responded to countless emergency calls, including fatalities, during his two-decade career. “There are a lot of other people who have suffered some significant losses here over the last few days as well, and my heart still goes out to them even though I am dealing with my own losses at this point.”

As Cranley spoke to Maclean’s via cellphone, he and Melonie were in Sherwood Park, just outside Edmonton, making funeral arrangements for a girl who should have celebrated her 16th birthday later this year. Aaron’s family had gathered there, too, many still wondering whether their homes back in Fort McMurray had survived the fire. “It is a nightmare,” says Dwila Hodgson, Aaron’s aunt, who works as a pipefitter. “It is a living nightmare. I don’t know how else to describe it.”

Aaron would have turned 20 on Aug. 3. Soft-spoken but extremely intelligent, he was a witty personality who loved Archie and Calvin and Hobbes as much as online video-gaming. Although he played guitar, drums were his instrument of choice. As a kid, Aaron collected high-end model cars, sporting a wide smile “that could only be described as magical,” says his uncle, Edward O’Brien. Misspelled words were his biggest pet peeve; his text messages were always immaculate, free of short form.

Aaron Hodgson, 19, died while fleeing the wildfire in Fort McMurray

Born in Fort McMurray, where both his parents’ families have lived for decades, Aaron moved east to St. Catharines, Ont., with his mother, Patti O’Brien, when he was eight. After high school graduation, though, he ventured back out west to live with his dad, Curtis Hodgson, an ironworker. (His older brother, Patrick O’Brien, a welder, also works in Fort McMurray.) Aaron wasn’t quite sure yet whether to follow his family into the trades or go back to school, perhaps in the field of information technology.

“He was just a sweet, kind boy who gave—to his friends, to his family,” Dwila says. “The world needs more people like him. It’s just a travesty that he’s gone.”

Another of Aaron’s aunts is Melonie Matthews-Ryan, who married Cranley last summer. Their wedding created, in her words, a “very, very blended family”: Ryan’s four children (the triplets, along with daughter Chelsi, now 22), and Melonie’s son, Nicholas, now 21 (who, along with being Aaron Hodgson’s cousin, was also his best friend.) At dinnertime, the entire clan sat together at the table. It was a rarity for any of them to miss a meal.

An aspiring nurse, Emily was the eldest of the triplets (Lucas came next, then Abby) and she always made sure everyone remembered her place in the pecking order. “I am the boss because I am the oldest,” she would often say. A voracious reader—especially the Harry Potter series—she was meticulous about her book collection. “She would read them without actually opening them all the way so she never cracked the spine,” her father says. “She has been a bookworm since she could pick up a book.” One of her final reads, it turned out, was Eleanor & Park, a teenage love story by Rainbow Rowell.

Emily Ryan, 15, died while fleeing the wildfire in Fort McMurray

“She was the loveable, ‘give me a hug’ kind of person,” says her stepmother. “We had parent-teacher interviews last week for the triplets, and every teacher’s room that we went into said the same thing: ‘Emily was everybody’s mother. She had to take care of everybody.’ ”

On April 29, the Friday before the fire, Emily had some medical appointments to attend. Her dad was off work, so they went together. “We didn’t get to spend that time very often, one-on-one,” Cranley says. “It was a beautiful day. We parked downtown, and instead of driving, we walked from store to store and appointment to appointment. We never really bought anything. We were just spending time.”

Four days later, Tuesday, May 3, the city was ablaze. Dispatched to Beacon Hill, one of the hardest-hit neighbourhoods, Cranley realized that his in-laws, William and Christine Matthews, needed to leave—immediately. He phoned Melonie and told her to get them out. “My son and I met in Beacon Hill when Cranley called,” she says. “When we were driving out—my son’s car, my car, and my dad’s car—there were flames dripping on our vehicles.

We were driving through pitch-black smoke and fire everywhere.” They managed to make it safely back to Saprae Creek, not far from the airport.

Aaron Hodgson was also in Beacon Hill as the fire intensified, but his father and brother had been out of town for a few days. He threw some clothes and his computer into his Chevrolet Avalanche and steered toward Nicholas’s house. By 8 p.m., the deputy chief phoned his family again. The fire was blowing toward them, he told his wife. “He said: ‘I can’t come, I have to stay fighting the fire. But you need to pack up the kids, and any other people in the neighbourhood, and you need to get them out,’ ” Melonie recalls. “It was hard to take the kids and go without him, but I just had to do it for him.”

“There was fire on both sides of the vehicle the whole way out,” she continues. “When we got out of the black smoke and could actually see where our vehicles were going, there were RCMP and other people helping, and they all had gas masks on in order to breathe while they directed traffic. It was something out of a horror movie.”

They managed to reach Anzac, 50 km south of Fort McMurray, but the community centre was overflowing with evacuees. They camped out for the night instead. Aaron helped pitch the tents.

Back home, Cranley and his crew worked through the night. It was 4:30 Wednesday morning when he finally went home to take a shower. He lay down in bed for maybe an hour—“awake with my eyes closed,” as he puts it—before jolting up and reporting back for duty. “It was like a war zone,” Cranley says, describing the wildfire’s wake. Among the many houses burned to the ground was his in-laws’ home in Beacon Hill.

As the clock ticked toward noon on Wednesday, Cranley’s family was back on Highway 881 south, putting more distance between themselves and Fort McMurray. When they reached the hamlet of Conklin (population 300), they found a makeshift welcome centre with cold drinks, hamburgers and hot dogs. Everyone devoured a good lunch, their best meal in about 16 hours.

The plan was to keep going, first to Lac La Biche, then eventually to Edmonton. They were a convoy of four vehicles. A minivan was in the lead, with Melonie and her parents inside. Nicholas and Lucas were behind them in another car. The third vehicle belonged to a neighbour, with Abby inside. At the tail end of the convoy was Aaron’s Chevy Avalanche, with Emily in the front passenger seat. (Chelsi had fled Fort McMurray with her boyfriend.)

The convoy was about an hour removed from lunch when Melonie’s dad, behind the wheel of the minivan, looked into his rear-view mirror. He saw Aaron’s vehicle slowly veer into the opposite lane. “I just heard my dad say: ‘Oh my God, he’s crossing over,’ ” Melonie says, holding back tears. “I turned immediately and saw the explosion.” The Avalanche smashed head-on into a tractor-trailer, bursting into flames.

As soon as her dad slammed on the brakes, Melonie jumped out of the van and sprinted toward the fire. “It just kept exploding,” she says. “All I could do was lie in the ditch and watch their vehicle burn.” Minutes later, deputy chief Ryan answered his cellphone.

Everyone is convinced—and the evidence certainly suggests—that Emily and Aaron fell asleep in the front seats, utterly exhausted by the chaos of the past day. One thing is certain: although they were nowhere near the Fort McMurray wildfire, it was the flames that ultimately killed them.

“This accident was directly because of this fire,” Dwila says. “There is no way they would have been on that highway if not for this fire, and when people say there were no casualties, that’s not true. There are two now.”

For the families left behind, their only consolation has been the overwhelming support they’ve received, much of it from strangers.

Some of Aaron’s extended family booked rooms at the Hampton Inn in Sherwood Park, and when the owner heard what happened, he not only offered to waive the bills, he hosted an impromptu memorial reception. Emily’s loved ones, meanwhile, have received hundreds of texts and Facebook messages from friends and neighbours, each one helping to ease the immeasurable pain.

Cranley also heard from colleagues in Fort Mac. They made sure to stop by his home and collect some of Emily’s personal belongings from her bedroom, just in case the house didn’t make it. “Once I knew that they went in her room and got her stuff, I didn’t need any updates after that,” Melonie says. “Nothing else really matters.”

Cranley, a firefighter to the core, says he simply wants to thank all the emergency responders who have worked so tirelessly to save the city he adores. “Professionally speaking, if we get through this whole thing and the only loss of life is two people, that’s a huge win for emergency services,” he says. “It’s just sad that they’re mine.”

As for his daughter, he wants Canadians to do one thing in Emily’s memory. “Please don’t dog-ear the pages of your books,” he smiles. “She really took care of her books. She really valued that.”

Aaron was an avid reader, too, which helps explain why he was such a stickler for proper spelling. His friends and relatives can’t count the number of times he chided them for their sloppy writing. Their only hope now is that people remember the 19-year-old not for the headlines his death generated, but for the genuine person he was: thoughtful, introspective, loyal and generous. “He was my sweet little boy,” his mother says.