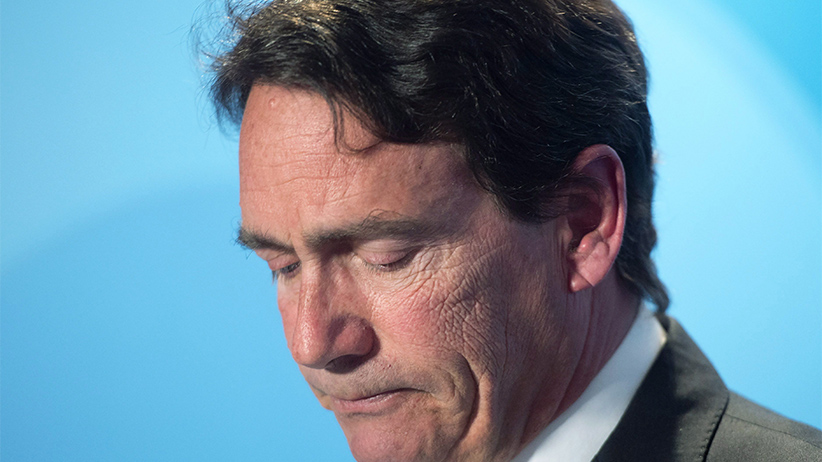

Pierre Karl Péladeau: A man of brash impulses gives in to another

Pierre Karl Péladeau exits politics just as he arrived: hastily. Martin Patriquin on the former Parti Québécois leader’s surprise resignation

Canadian media tycoon Pierre-Karl Péladeau visits a music store on March 27, 2014 in Saint-Jérôme, Canada. Péladeau announced on March 9 he would run as the Parti Québécois candidate for the Saint-Jérôme provincial electoral district, 60kms (37 miles) northwest of Montreal. The party has welcomed Péladeau’s commitment to an independent Quebec. The elections are scheduled for April 7, 2014. (Francois Laplante Delagrave/AFP/Getty Images)

Share

Just over two years ago, Quebec businessman Pierre Karl Péladeau announced his intention to run for the Parti Québécois by way of a hastily staged press conference with PQ leader Pauline Marois. As to why a billionaire businessman would get into the often unpleasant reality of politics, Péladeau invoked his three children by name. “I hope to help give them a country in which they will be proud!” Péladeau said. A few minutes later, he ended his announcement on an even more quotable note. “My support of the Parti Québécois is an adherence to my most profound convictions: to make Quebec a country!” he said, stabbing his fist in the air.

It is a mark of the man as well as the party he led for less than a year that Péladeau, in announcing his immediate resignation from the party, again invoked his children and his belief in a separate Quebec. This time, though, his offspring and the fate of the nation were less simpatico than the subject of what Péladeau called “an agonizing choice between family and my political project.” Like most politicians beating a hasty retreat from politics, he chose family. By his own logic, his dreams for his children will suffer as a result.

Péladeau is an impulsive man, and in these two announcements bookending his political career, we see the marks of a man who makes very big decisions in a very short time. In 2014, Péladeau was a political cipher. Before 2010, he had never donated to the Parti Québécois. Like many members of the province’s typically federalist business elite, his dollars mostly went to the Liberal Party of Quebec. He launched the Sun News Network, whose shout-y right wing populism was tightly swathed in the Canadian flag.

His father, Pierre Péladeau, launched Le Journal de Montréal in part as a model of the Parti Québécois’ social democrat principles, with a raft of lefty columnists and the best collective agreement for its journalists. During Pierre Karl Péladeau’s reign, the Journal’s editorial brain trust torqued to the right, and he locked out those very journalists in what became one of the longest enforced work stoppages in the province’s history. He courted Quebec’s very lefty, very sovereignist artistic class, but before his political sojourn never declared himself sovereignist (or, gasp, lefty) himself.

Péladeau found a willing partner in the Parti Québécois nonetheless, if only because the party was so lacking for a saviour. In 2014, after just 18 months in power, the party suffered its worst electoral showing in terms of popular vote in its history. Suddenly, Péladeau’s contradictions became his best selling point: a right-of-centre businessman who found himself suddenly delighted by the PQ’s lefty, sovereignist underpinnings.

From the archives: Martin Patriquin’s 2013 profile of PKP

During his leadership campaign a year ago, I watched as he broke out into a warbly version of L’internationale, the anthem of proletariats everywhere, in a sweaty brasserie in east end Montreal. I remember thinking that any politician who can pull of that kind of conversion with such evident glee deserves to be leader of something. And when he routed his opponents in the ensuing leadership race, the PQ believed it had its saviour—a former strike breaker who suddenly wanted very much to be on the picket line.

His tenure as Parti Québécois leader was a truncated version of what generally happens to those who lead the party. Propelled to the helm of the party on the dreams of its members, Péladeau smacked head-first into the realities of Quebec politics. He never made much of a dent in the Liberal government’s popularity, despite the governing party being burdened with scandal and a vision-free mandate. Michel David, a columnist at the nationalist Le Devoir, came very close to calling Péladeau an idiot.

In January, certain members of his caucus began expressing misgivings about his performance; PQ MNA Martine Ouellet, particularly, bemoaned Péladeau’s inability to counter the Liberals’ recent austerity measures. Prophetically enough, Ouellet told a close colleague that she didn’t think Péladeau would make it to the PQ’s convention this fall.

Yet there were signs, at least, that Péladeau was going to be sticking around. Last week, he replaced his chief of staff, the very unpopular Pierre Duchesne, with Annick Bélanger. As recently as 10 days ago, according to political pundit Mario Dumont, Péladeau was working on party strategy in preparation for the 2018 election. These aren’t the moves of a man angling for the exit.

With the unceremonious departure of yet another Parti Québécois leader, we now enter into another familiar exercise: finding the party’s next would-be saviour. Véronique Hivon, the party’s justice critic and chief author of the province’s assisted dying law, would make a fine leader—though she has repeatedly said she isn’t interested. Education critic Alexandre Cloutier ran against Péladeau for the leadership last year, and at 39 would be a youthful shot to what has become a Baby Boomer movement. Former Péquiste Jean-Martin Aussant is another name being bandied about.

As for Péladeau, he will likely venture back to Québecor, the company his father begat him and where he made his name. For all his impulsiveness, Péladeau had the good sense to never get rid of his Québecor shares. He will be much richer for it in political retirement.