Promoting religious freedom is complicated: extreme caution advised

One has reason to doubt that the government is undertaking the careful thinking necessary

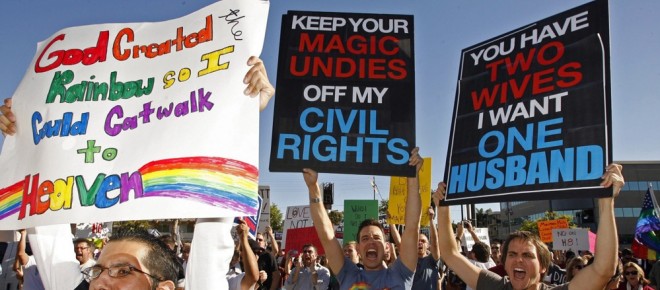

FILE – Protesters hold signs in front of the Mormon Church during a “No on Prop 8” rally in Los Angeles to protest the church’s monetary support of Prop 8, Nov. 6, 2008. The anti-Mormon backlash after California voters overturned gay marriage last fall is similar to the intimidation of Southern blacks during the civil rights movement, Elder Dallin H. Oaks , a high-ranking Mormon says in a speech to be delivered Tuesday Oct. 13, 2009 at Brigham Young University-Idaho. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes, File)

Share

The New Missionaries is a joint project between Maclean’s and OpenCanada.org, the Canadian International Council’s (CIC) hub for international affairs. Click here to learn more about the CIC. To read Clifford Orwin’s defense of the Office of Religious Freedom, click here.

The promotion of freedom globally, if done peacefully—without invading armies, bombs, and the resulting carnage—can be a fine thing. But creating an Office of Religious Freedom, as the Canadian federal government is in the process of doing, may not be such a good idea. To test whether it is, there are three questions Canadians should insist be answered before the office starts its work.

The promotion of freedom globally, if done peacefully—without invading armies, bombs, and the resulting carnage—can be a fine thing. But creating an Office of Religious Freedom, as the Canadian federal government is in the process of doing, may not be such a good idea. To test whether it is, there are three questions Canadians should insist be answered before the office starts its work.

First, is there a strategy in place for dealing with conflicts between religious freedom and the protection of other human rights? In Canada, we are quite clear: the oppression of women or vulnerable minorities will not be tolerated in the name of religious freedom. But how will the new Office of Religious Freedom respond when other human rights interfere with the rights claimed by religious groups in other countries, for example, to marry young girls off long before adulthood, or to impose rules that blatantly discriminate against women in religious courts, or to ban gays from places of worship?

There must be protocols in place for handling the inevitable conflicts between the exercise of religious freedom and other human rights. And these protocols must be consistent with Canadian values, which include, but are not limited to, religious freedom.

Secondly, are we confident that the office will promote freedom of religion, not religion itself? The advocacy of human rights is a legitimate activity for government, but the direct promotion of religion is not. Indeed, the promotion of religion by government would be unconstitutional: it is crystal clear in Canadian law, as articulated by the Supreme Court of Canada, that freedom of religion includes the right to not follow any religion at all. The right to reject religion is every bit as protected in Canadian law as the right to follow the faith of one’s choosing. Is the Office of Religious Freedom going to advance both with equal gusto, or is its real reason for existence to promote religion?

Finally, why are we focusing on freedom of religion instead of freedom of conscience and religion? The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees both “freedom of conscience and religion” (emphasis added). One of the rights people hold most dear is the freedom to live according to the values they believe are paramount—that is, to live as their conscience indicates they should. For some people, those paramount values relate to ideas about the creation of the world, the supernatural, or the divine. The values felt most binding by others relate to environmental protection, paying homage to animals their culture depends upon (such as the buffalo or bear), or the ethical imperatives of social justice, such as the need to eliminate poverty. All such frameworks of belief—both the religious and non-religious—are matters of conscience, and all need to be supported by an office devoted to freedom of conscience and religion.

Unfortunately, one has reason to doubt that the government is undertaking the careful thinking necessary to run a sophisticated Office of Religious Freedom. It is worrying that organizations such as Amnesty International Canada, which have significant expertise on clashes between human rights and religious freedom globally, were not invited to a recent consultation on the creation of the office.

Canadians need to know that the Office of Religious Freedom is going to be informed by really good thinking. Freedom, rights, conscience, and religion are all much too important to be treated in a cavalier fashion.

Janet Keeping is the president of the Sheldon Chumir Foundation for Ethics in Leadership.