René Angélil: The Svengali behind Céline

René Angélil turned a 12-year-old Quebec girl into a global sensation. How they became a business juggernaut and an unassailable force in Quebec.

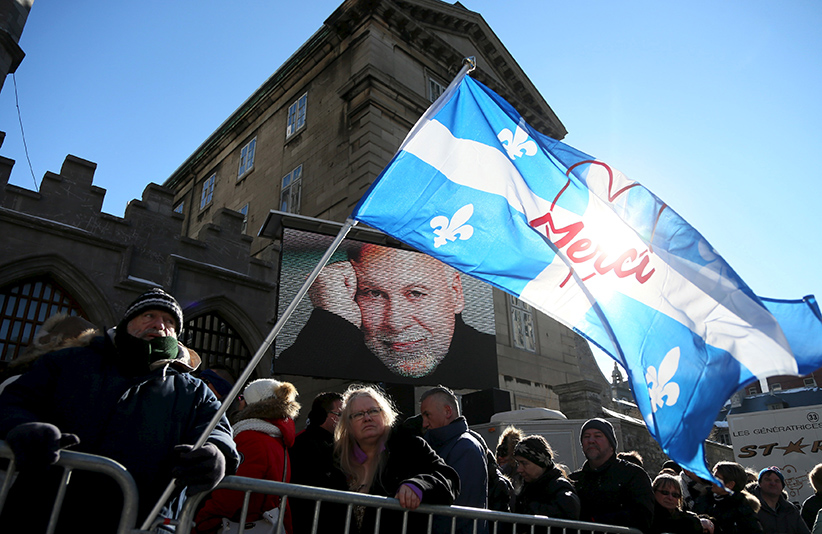

Celine Dion fan Adam St-Couer (L) holds a Quebec flag as he waits in line to be admitted for the funeral for Rene Angelil at Notre Dame Basilica in Montreal January 22, 2016. (Christinne Muschi/Reuters)

Share

At three o’clock on Thursday, Chantal Dugré was part of the huddled, shivering and mostly graying masses lined up in front of Notre Dame Basilica in Old Montreal, awaiting their turn to pay respects to the manager, producer, business partner, husband and father to the children of one of this country’s biggest cultural exports.

“I met him in 1991,” Dugré, 50, said. “It was right after Céline had released Unison, her first English album. I met him on the stairs before the concert. He said hello to me in that voice of his. He had beautiful teeth. He was beautiful. From then on I began to love him intensely.”

Not many men elicit this sort of response from perfect strangers 22 years their junior. But so it went with René Angélil, who died a week ago and whose funeral you could watch on TV if you were so inclined. Of course, Angélil wasn’t really a stranger; since 1981, when he discovered an awkward country girl named Céline Dion, Angélil has been intimately involved in the ensuing Céline juggernaut.

They married at Notre Dame in 1994, and days later renewed their vows near their Las Vegas home. Men in matching fez hats carried them to the altar in matching white leather chairs. Belly dancers and a camel were present. This contrast—subdued if resplendent French Catholicism, followed by Vegas-stlye bacchanalian reverie—is a perfect summation of what the juggernaut had become by the time Angélil succumbed to throat cancer at the age of 72.

So apparently important was his contribution to Quebec that Premier Philippe Couillard immediately declared national funeral rights for the impresario, only the 10th such thing in the province’s history. “Quebec has lost a huge figure in the industry of spectacle,” Couillard said. It has lost part of its collective fairy tale as well. Even though that fairy tale had long decamped to a Las Vegas mansion and a standing gig on the Strip, Angélil made pains to ensure Céline remained notre Céline (our Céline) in her native land—a world superstar who was as wholesome, uncomplicated and beatific as her 12-year-old self.

Angélil learned the rudiments of pop stardom creation early. Born to Syrian parents in 1942, he grew up in Villeray, then as now a teeming multicultural Montreal neighbourhood. He took to gambling and music in short order; the former, because his grandparents and parents were gamblers, the latter because of his fascination with Elvis Presley.

In 1961, he and two high school friends formed the Baronets, a singing trio that on paper sounded like the prelude to a punchline: an Arab, an anglophone and a French Quebecer dress up in suits. The Baronets did well on Quebec’s nascent talent show circuit by singing a mix of Elvis covers and original material, eventually graduating to dates at Montreal night clubs.

By translating hit songs into French, the trio tapped into a uniquely Quebec niche, garnering mostly female audiences who suddenly could understand the sweet nothings Elvis had crooned in English. The Baronets changed with the times, replacing Brylcreem with mop tops to sing the Beatles, thus fomenting a French version of Beatlemania. “Hold Me Tight became “C’est fou mais c’est tout”; “Twist and Shout” became “Twiste et Chante.” They were cultural cyphers willling to take on whatever was the next thing. “[Angélil] thought the group would be able to adapt to every change in fashion,” as Jean Beaunoyer wrote in an unauthorized biography of Angélil in 2004.

Egos and money got in the way, as did Angélil’s profligate gambling, and in 1972 the Baronets disbanded. By then, Angélil had turned to managing. His first protégée was a handsome blond 20-something name Muguette, who had a minor hit with a French version of “These Boots Were Made For Walkin’. ” He was married and had a child. His stab at U.S. success, with Quebec singer Ginette Reno, maddeningly collapsed before fruition. He was as broke as could be.

In 1981, at the behest of a producer friend of his, Angélil went to hear Dion sing. He met a tall, skinny 12-year-old girl with thick eyebrows and big teeth, with insecurity to match. Given a microphone, though, she had what Angélil discovered to be “a marvellous voice, a restrained passion and a desire to sing,” as Beaunoyer wrote.

Everything else, admittedly not much at the time, was dropped. Céline became Angélil’s sole source of attention. Her manager was dispatched, he befriended the family—particularly Céline’s mother, Thérèse, who was almost as impatient as Angélil to see Céline’s name in lights. He hired songwriters and shooed away prospective suitors, so as not to distract her. Angélil’s second wife, Anne Renée, a former singer herself, taught Céline how to carry herself in public and address crowds. Despite their age difference, the pair became fast friends.

How and exactly when Angélil and Dion went from business partners to lovers remains one of the more squeamish topics in Quebec, one often papered over or handled with a particularly thick pair of kid gloves. According to Beaunoyer’s unauthorized biography, it was Dion who seduced Angélil, who had divorced his first wife in 1972. This Lolita-like narrative hasn’t really been dissected further; certainly, no one ever challenged Angélil on the 26-year age difference between the two, lest they get sued to blazes. Instead, their union is the stuff of fairy tales, the consummation of a beautiful (and remarkably lucrative) partnership.

Released in 1990, Unison was Dion’s 12th album. As her first English-language effort, it was the Baronet formula in reverse: English songs sung in a slight French lilt for a largely American audience. It sold three million copies, juiced by the single “Where Does My Heart Beat Now.” Since Unison, her discography has been a nearly perfect tandem of French and English albums. Singing in English is normally verboten for Quebec stars, yet for Dion it had the opposite effect. Her superstar status dictated she sing in English, but she always came back to French. She’s notre Céline, after all.

Though he managed one of the biggest stars on the planet, Angélil remained particularly obsessed with Dion’s image in Quebec. In 2002, René Angélil threatened to sue two Montreal radio DJs after they parodied one of Dion’s songs, claiming the duo had attempted to piggyback on Dion’s popularity. Coming from a guy who made his bones singing translated Beatles songs, it was a bit rich; Angélil further demanded the station stop making fun of him, and cease playing (real) Dion songs.

A combination of sanctimony and litigiousness made the couple virtually untouchable. When comedian Mike Ward told several jokes about the couple during a recent show, most of the laughs came when Ward bemoaned the eventual lawsuit from Angélil. “People act like if you insult Céline, it’s like you’re insulting Quebec. The bit was practically construed as Quebec-bashing,” Ward says. (Angélil never threatened to sue the comic.)

Only with his death, it seems, have people been willing to publicly criticize Angélil. The decision to give a man who made his fortune in English and his home in Las Vegas a national funeral has ruffled feathers in Quebec’s cloistered cultural milieu. “It’s not the cost that bothers me, but what the funeral says about us. The celebration of bling-bling, the use of talent for purely commerical ends,” wrote actor and theatre director Raymond Cloutier.

It was a broadside against the Angélil legacy, a putdown rarely heard when the svengali was alive. Several hours later, Cloutier removed it from Facebook entirely. Even in death, Angélil still has pull.