Why nobody wants to lead B.C.’s official Opposition

The B.C. NDP leadership race isn’t exactly a race with just one candidate

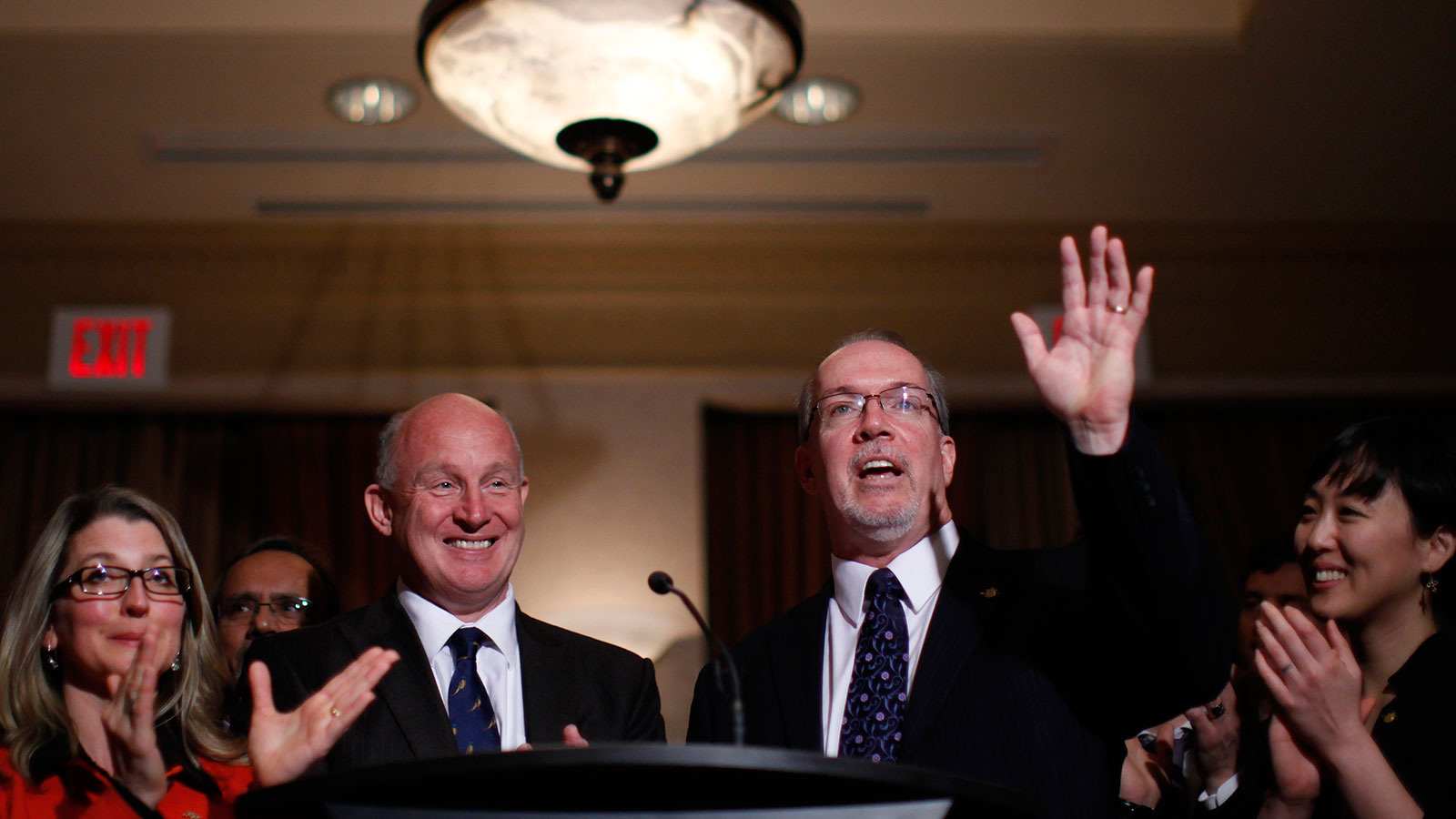

Chad Hipolito/For The Globe and Mail

Share

The second-worst white-collar job in British Columbia, behind coaching the Vancouver Canucks, would be leader of the provincial New Democrats. It’s been almost a year since the May 14 provincial election that saw party leader Adrian Dix blow a 20-point lead and lose the premiership to B.C. Liberal Christy Clark. And it’s almost eight months since Dix said he’d resign as soon as the party elected a new leader—the sort of blood-in-the-water opportunity that should have triggered a feeding frenzy among the party’s political piranhas. But weeks before the May 1 nomination deadline, there is just one person in the running.

Well, running is an extreme word, it being a non-race. It’s more apt to say John Horgan, a veteran Victoria-area MLA and one-time party apparatchik, is shuffling toward his apparent coronation. Contrast this to the Parti Québécois, another campaign disaster. There, Premier Pauline Marois hadn’t announced her resignation before party operatives were after her job. While they were condemned for over-ambition, they at least showed the PQ is worth fighting for.

So what gives in British Columbia? The past NDP line was that a leadership race and a fall convention would generate excitement, refresh its policies and open the tent to a stampede of new converts. But unless a second contender pays the stiff, non-refundable entry fee by May 1, Horgan will have bought the leadership of the official Opposition for $25,000. It’s not clear that’s a bargain. Past leaders—with the exceptions of Dave Barrett, Mike Harcourt and Carole James—have the life expectancy of pet goldfish. Even leaders who actually won elections—Barrett in 1972, Mike Harcourt in 1991, Glen Clark in 1996—exited bruised, bloodied, and denied second terms as premier.

After four straight campaign losses, a cogent argument can be made that the party needs policy renewal, and “next generation” leadership. The latter phrase, ironically, was uttered by 54-year-old Horgan last fall when he announced he wouldn’t seek the leadership because the NDP needed young blood. But potential candidates sat on their hands. Four federal NDP MPs—Peter Julian, Fin Donnelly, Jinny Sims and Nathan Cullen, an early favourite—all took a pass, saying they were committed to their federal duties. David Eby, an ambitious first-term Vancouver MLA, cited his wife’s pregnancy. Finally this March, 54-year-old provincial opposition finance critic Mike Farnworth announced his candidacy, though he never got around to ponying up the entrance fee. Party stalwarts were underwhelmed. Horgan was lured into the race with sizable financial support and caucus endorsements. Farnworth, in a kumbaya moment last week, stepped aside in the name of unity and endorsed Horgan. That saved him $25,000, and the cash-strapped party the expense of a convention.

Acclamation avoids a wrenching policy debate between Horgan, who is vaguely in favour of more natural resource development, and the so-called BANANA wing (Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere Near Anybody) that had Dix in its thrall. But if the party is too indifferent to debate such matters, critics ask, why should the public engage?

Michael Byers, a University of British Columbia political scientist and former federal NDP candidate, has a different take. He considers Horgan, with his “natural charisma” and party pedigree, all but unbeatable. New Democrats he’s canvassed have “a deep level of satisfaction” with his coronation. “When you already know who’s going to win, why not spend that time and energy preparing for the next election campaign,” he asks. “Why not have a policy convention rather than a fake leadership convention?”

There may also be urgency to get a new leader in place to stem an erosion of key support. Clark has opened the Liberal tent to unions, making them partners in her aggressive push on LNG development and resource extraction. Dix’s campaign, with its urban, soy-latté sensibilities, lost union votes in mining, forestry, construction and oil and gas.

Dawn Black, a former NDP MP and MLA, had hoped a leadership race would be a catalyst to “reinvent” the party and shift its policies to foster “environmentally responsible” economic growth and resource development. “Unable to confidently articulate an agenda built on economic growth and redistribution, the B.C. NDP has become a conservative force, fighting to protect the gains of the postwar boom but also resistant to new ideas for a changing world,” she wrote as co-author of an article for the Vancouver Sun. “More equal societies are better societies,” she said. “But they don’t come free. They are paid for by economic growth.”

What, if anything, the NDP lost by not thrashing that out before anointing a leader remains to be seen. Certainly an uncontested win is no guarantee of party unity, as former premier Harcourt knows. His acclamation was a strange burden “that could only happen in the NDP,” he wrote in his biography, A Measure of Defiance. “The good news is you won the leadership. The bad news is that some people within the party resent the fact you won the leadership.” Like Dawn Black said, good things don’t come free.