The poppy papers: notes for Remembrance Day

At the Canadian War Museum, visitors scribble notes on pieces of poppy paper that will later be planted: ‘Dear dad,’ one writer began

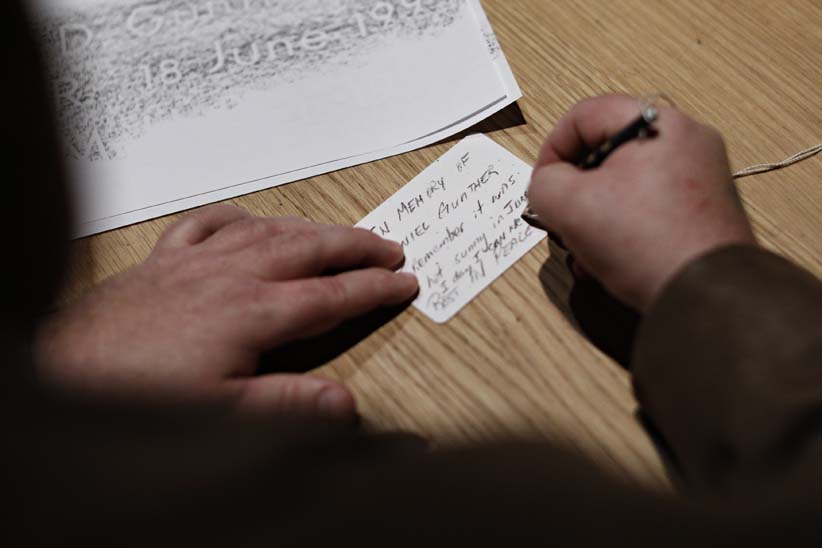

Garth Wetherall writes a message on a piece of paper embedded with poppy seeds to his Great uncle Charles Parks, who served in WWI, that will be planted by the Canadian War Museum, in Ottawa November 10, 2017. Photograph by Blair Gable

Share

Forget Parliament for a moment—the tax tiff, the papers leaked from paradise. Down the street at a museum exhibit, visitors hunch on wooden stools and write on slips of paper. “Miss you Dad. Rest easy,” reads one of the notes pencilled at the Canadian War Museum, as part of a project called Memory Garden, which gathers these notes from April 9 to Nov. 12. “Dear uncle,” begins another. “To those who never returned and to the ones who did but not completely.”

The papers are ingrained with poppy seeds, so they will be planted on the museum’s roof come spring. Messy with smiley faces, the papers are a humble tribute to the soldiers, children, Indigenous fighters and other people who paid their dues in the wartime currency of lives, trauma and body parts, before and since the end of the First World War on Nov. 11, 1918. Grander memorials soar in war monuments across the country, but these squares of poppy seed paper just as genuinely jog the memory.

“He was the nicest guy on earth,” reads one paper slip, now stored in a glass case with hundreds of others. The museum granted permission to Maclean’s to read the ones that were visible through the glass. Another goes, “Thank you for the future.” Some stanzas trace family trees; some writers seem to squeeze in works of flash non-fiction, while one person offers a single abbreviated, “THX.”

More iconic war tributes include the Halifax Memorial and the National War Memorial next to Parliament Hill, honouring troops including those in World War One, who were by definition the country’s most promising men (required to be at least five feet tall with sound eyesight and teeth), if not teenagers who lied about their ages for national pride and the base salary for a private in the Great War, $1.10 per day.

RELATED: Watch Remembrance Day at the Canadian War Museum: Live video

Yet, the poppy notes, too, commemorate the 420,000 Canadians who served in the First World War, which, as explained elsewhere in the museum, killed Japanese Canadians, and a talented Ojibwa sniper, and could’ve killed Lester B. Pearson if he’d been sent to the western front before getting serendipitously hit by a bus.

Some poppy notes commend soldiers specifically for the Battle of Vimy Ridge, where Canada lost 3,598 troops before conquering the German-held hill called “The Pimple”. “They could not talk, they would not tell us,” reads one note. “You had lost your voice. Your life. The pieces left behind are the puzzle that my heart embraces. The picture is coming through.”

Today, an 8-year-old Penelope and other poppy note writers can enjoy freedom from conscription, freedom from barbed wire and the luxury of visiting a war museum that expects up to 3,500 visitors on Remembrance Day, when even tickets are free.

“I got mad at my parents ‘cause they didn’t stop at KFC, and I was starving …” One eighth grade visitor paused her account of such food deprivation to explain the note she’d written to fallen soldiers—“thanking them for their bravery.” Those men, frostbitten in early trench coats, subsisted on corned beef and “a kind of dog biscuit,” as one soldier quoted in the museum described, in which “the chief ingredient is, I think, cement.”

“Dear Dad,” began one writer, who wished to keep his note private. “Papa,” started another, “mon coeur pleure,” and “to my wonderful grandmother.” Their notes will grow into poppies so they will not forget, for they should never say “never” except in November, and the roof will be red in the springtime.