‘Toronto 18’ judgment: the RCMP’s prized mole is vindicated

A court says undercover informants don’t have to warn young people not to get involved in terror plots

Simon Hayter

Share

It has been almost seven years since police rounded up the so-called “Toronto 18,” thwarting a very real terrorist plot on Canadian soil. In time, the Crown and the courts separated the ringleaders from the stooges: charges were dropped against seven of the accused Muslims, while the other 11 were convicted and punished according to their level of guilt. Of the four core members who tried to detonate simultaneous truck bombs in downtown Toronto—a “spine-chilling” plot, as one judge said—two are now serving life sentences.

But even after so many years, the courts are not quite finished sifting through Canada’s landmark anti-terror bust. The latest judgment comes from the Court of Appeal for Ontario, and although it won’t be the last, it does settle one contentious question that emerged at trial: if authorities are investigating a group of aspiring terrorists, and some turn out to be teenagers, do the police have a legal obligation to somehow warn the youth to be wary of the leaders?

The answer, says Ontario’s highest court, is an emphatic no. “To impose on the police an obligation to ensure that undercover operators infiltrating a potential terrorist camp be equipped with some sort of strategy to warn youth (who may or may not be present) of the potential error of their ways, is neither tenable nor realistic,” the court concluded. “The prospects of such a strategy subverting the investigation, and possibly endangering the safety of the operative, are limitless.”

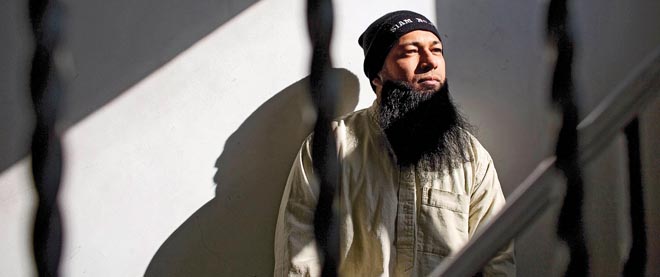

The ruling is a resounding victory for the RCMP—and vindication for Mubin Shaikh, the controversial civilian informant who was paid $300,000 to infiltrate the inner circle. “When the top court backs your actions, how can you not feel good?” says Shaikh, now 37. “It is so clichéd, but you have to stand for what is true, even if you stand alone. In the end, I knew I was doing the right thing.”

The pinnacle of Shaikh’s undercover work was a now-infamous winter “training camp” near Orillia, Ont., where a dozen participants spent two weeks marching in the snow and learning to fire a semi-automatic handgun. One of those campers was a 17-year-old who had recently converted to Islam—and who would later become the youngest of the group convicted and sentenced (to 30 months).

Appealing the guilty verdict, the teen’s lawyers took direct aim at the RCMP’s prized mole, arguing that Shaikh’s conduct at the camp was so egregious it would “shock the conscience” of Canadians. He didn’t merely attend, the defence argued, he was a leader, the one who specifically taught the others to fire the gun. “This case is based upon a state agent crossing the boundaries of fair play by providing terrorist training to a youthful, naive, Hindu convert,” the defence argued. “Failure to control state agents in this regard not only offends the community’s sense of fair play and decency, but is an institutional failure that must not be condoned.”

Again, the appeal court disagreed. Writing for the unanimous panel, Justice Robert Blair said the camp would have occurred with or without Shaikh, and anything he did, including the firearms training, was at the behest of the ringleaders. “While undercover operatives in Shaikh’s position are required to act within the parameters of the law,” he wrote, “it is unrealistic—given the seriousness and urgency of the situations in which they find themselves—to expect that they will be able to act as if they were unvarnished models of purity, and both refrain from engaging in the activities they are underground to investigate and dissuade other participants from getting drawn into those activities.” Regardless of their age.