What the tragedy of Colten Boushie says about racism in Canada

Andray Domise on how the young Indigenous man’s death is yet another reminder of lessons still not learned by many Canadians

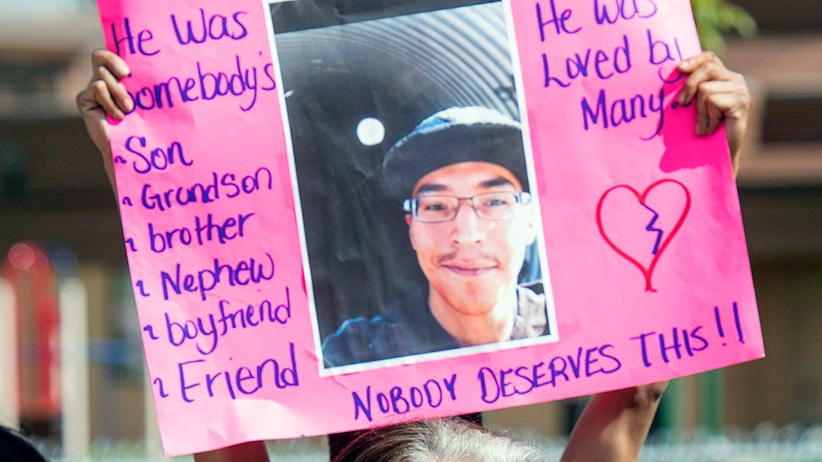

Colten Boushie, a 22-year old First Nations man, was shot and killed on Aug. 9 after the vehicle he was in drove onto a farm in the rural municipality of Glenside, west of Saskatoon. (Liam Richards/CP)

Share

“In my culture, you’re not supposed to name the dead,” she says. “At least not for the first while, or they might not be able to move on. But I had to say something. People had to talk about him, or nothing was going to happen.”

Chelsea Vowel, an Edmonton-based Métis educator and writer, is speaking about the death of 22-year-old Colten Boushie. Throughout the conversation, Chelsea wavers between righteous strength and tearful exhaustion. By the accounts so far, Boushie did not have to die. And yet the young man was laid to rest last week, gunned down in rural Biggar, Sask., after an altercation with farmer Gerald Stanley. Stanley now awaits trial for second-degree murder.

“They think they know about Indians,” Chelsea says, of non-Indigenous Canada. “They have this belief, that’s taught to them from birth, that everything Native people face is our own choice. Particularly in the Prairies, where there are very high populations.”

As Chelsea pours her heart out to me, I’m reminded of Claudia Rankine’s book Citizen: An American Lyric. Facing opposite a purposefully unfinished memoriam to Black men killed by police and white vigilantes, stand these lines:

because white men can’t

police their imagination

black men are dying

According to the friends who were with Colten, they were returning to the Red Pheasant reserve after an afternoon of swimming when their car tire went flat. They steered onto Stanley’s farm to seek help. Eric Meechance, who was sitting in the back seat of the vehicle with his girlfriend, described a rapid escalation to violence that ended with Colten’s death. “Some guy came and smashed in the front windshield,” he told the Saskatoon StarPhoenix. The frightened driver attempted to escape, but collided with another parked vehicle. Meechance and another of the car’s occupants fled on foot, and gunshots cracked behind him. The two were separated after Meechance ducked into bushes and ran two kilometres along a dirt road before being picked up by police.

Of those gunshots that split the afternoon sky, at least one of them killed Boushie.

In the aftermath of the shooting, the response from white Canada has limned in staggering detail our sins against the Indigenous body, and the ease with which we excuse our violence. First there was the RCMP press release, explaining matter-of-factly that the witnesses to Boushie’s killing—this is right after their friend was shot and killed—were taken into custody “as part of a related theft investigation.” None of the three were charged with any such crime. Then the racial animus began to seep out of the Facebook page for the Saskatchewan Farmers Group, with comments like “F–king indian,” and “He should have shot all 5 of them and given a medal.” Ben Kautz, a councillor for the Rural Municipality of Browning, Sask., had this to say: “In my mind his only mistake was leaving witnesses.”

Days later, CBC Saskatchewan published an article claiming that the social media debate in the wake of Boushie’s death was over the “right to defend.” In that piece, CBC interviewed a criminal defence lawyer who detailed the legal means by which killing an intruder on one’s property might be permitted. “Are these people known to them, or not known to them? Is there a history of violence between them or no history at all? Do the people appear armed or not armed?”

“When there doesn’t appear to be any reasonable alternative, lethal force is no doubt permitted.”

Enough people seemed to agree with the sentiment that a crowdfunding drive in the name of Stanley’s wife drew over $11,000 in donations before it was taken down by GoFundMe. Regular people, who probably consider themselves tolerant and enlightened individuals, opened their wallets to support a man who, purportedly, shot and killed an Indigenous youth.

At Stanley’s bail hearing in North Battleford, Indigenous groups and allied activists took to the streets in a demonstration of solidarity with Boushie’s family. Multiple witnesses, including Métis artist and author Christi Belcourt, snapped pictures of RCMP officers standing sentinel on rooftops surrounding the demonstration. According to Belcourt, officers were visibly armed, taking down their rifles as the crowd began turning cellphone cameras in their direction. Stanley, by the way, was granted bail. A privilege that too many Indigenous people have themselves been denied for far lesser crimes.

This past weekend, during the Tragically Hip’s last concert, beloved singer Gord Downie re-asserted Canada’s obligations to Indigenous peoples for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau: “He’s going to take us where we need to go. He cares about the people way up North, that we were trained our entire lives to ignore.”

To wit, Trudeau himself once declared: “It is time for a renewed, nation-to-nation relationship with First Nations peoples.” In addition to launching a public inquiry into the thousands of missing and murdered Indigenous women, Trudeau also promised to implement all 94 recommendations from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The TRC (which should be required reading for every Canadian who claims to understand our history) is a broad document that outlines the damage done not only by the horrific legacy of residential schools, but by Canada’s turning a blind eye to what we have wrought on Indigenous communities through purposeful neglect and wanton violation of our promises.

Those calls to action, even if fully acted upon by the federal government, ring hollow when Canadians, who think they know about Indians, misunderstand who and what they have been trained to ignore. The people who flooded the Saskatchewan Farmers Group with hateful comments, those who gave from their own accounts in Stanley’s name, the media who question where to draw the line between property rights and dead Indians, the councillor who regretted that Stanley failed to execute all of the passengers in that vehicle, and possibly Gerald Stanley himself—all bear the stain of Colten Boushie’s blood.

As do I, kidnapped body living on stolen land that I am.

As do you.

Because we cannot police our imagination,

Colten Boushie is dead.