On crime, Winnipeg achieves a minor miracle

Once near the top of Canada’s Most Dangerous Cities list, Winnipeg is now at No. 19

Share

In early 2008, then-Winnipeg mayor Sam Katz was sifting through crime data provided by Maclean’s, being told his city was the third most dangerous in the country. Sexual assaults were 50 per cent higher than the national average. Robbery rates were the second worst in the nation. A car, meanwhile, was 334 per cent more likely to be stolen in Winnipeg than in the average Canadian city. The crime data was grim, but Katz neither refuted it nor claimed the numbers were misleading. Instead, he talked about mothers putting their daughters on the street to pay for their addictions and auto thieves stealing cars to drive to court-ordered crime diversion programs.

RELATED: Canada’s most dangerous cities 2016: How safe is your city?

In short, Katz accomplished step one: admitting the city had a serious crime problem. The next step was to address it. “I hope the next time you and I talk,” Katz told Maclean’s in 2008, “we’re not in the top 10.”

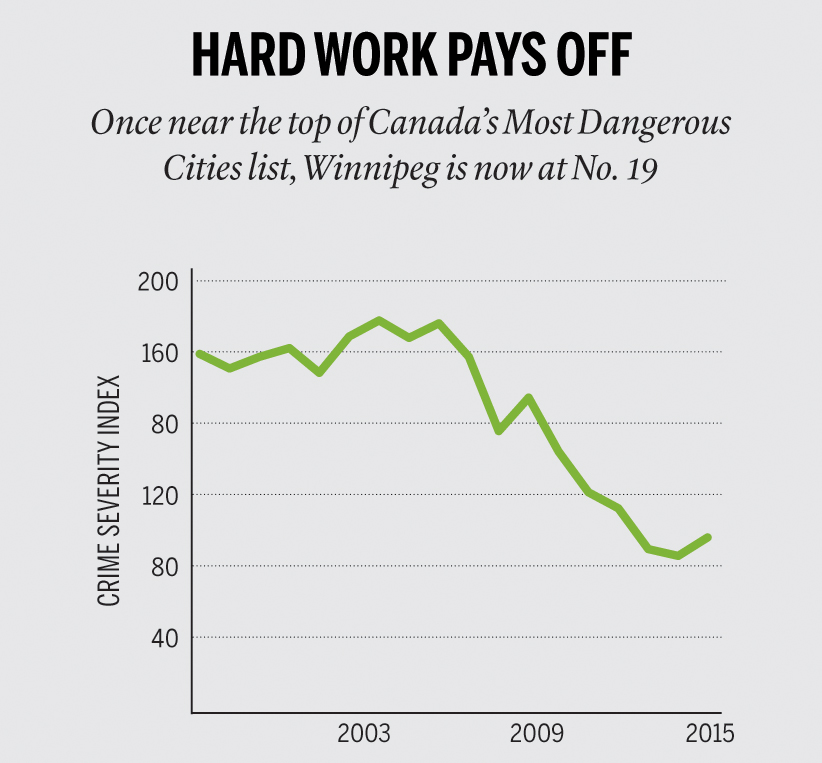

Fast-forward to now and impressive progress has been made. The city ranks 19th in crime (albeit by an upgraded methodology), with its Crime Severity Index score falling 1.6 times faster than the national average in the last decade.

What changed? For one thing, the city has made great strides in overcoming mistrust between the police and the city’s Aboriginal community, says Keith McCaskill, the city’s police chief from 2007 to 2012. “We felt if we were going to start creating a safer community, we have to build strong relationships.” And that meant providing his officers with more time to cultivate those relationships by freeing them from routine obligations. McCaskill helped create a second tier of policing, known as cadets, to handle smaller tasks like traffic duty and guarding crime scenes.

To tackle auto theft, police teamed with Manitoba Public Insurance to encourage car owners to install ignition immobilizers, which require a fob on the owner’s key chain to turn on. Winnipeg’s motor vehicle theft ranking has since dropped from first to 19th.

When Devon Clunis took over as police chief in 2012, he “challenged our police officers to be community builders.” Clunis, who recently retired, argues the cure for the city’s crime problem isn’t more law enforcement, but rather “crime prevention through social development.” For instance, the vice unit would arrest prostitutes and later release them under condition they not be in certain parts of town, but Clunis had a problem with going after women who were being exploited. “Let’s not further victimize them,” he says. So the squad was renamed the Counter Exploitation Unit and began targeting johns and pimps. The women being prostituted were offered help if they wanted out of the sex trade. The police’s gang unit also hit on the idea of going to gang members’ homes to “meet with the caregiver to see if there are any siblings we can steer in the right direction rather than let them get into the same lifestyle.”

Winnipeg’s new policing mindset got a big assist from the city’s economic revitalization. The beloved Jets returned in 2011. The city welcomed the Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Even Ikea opened up in 2012. “This probably is not a big deal for a place like Toronto,” says Michael Weinrath, a University of Winnipeg criminologist. “But when you’ve been in decline since the 1970s, those positive things are important.”

All is not perfect. The city ranks ninth worst for sexual assault and 11th in homicide. The odds of getting robbed in Winnipeg are one in 496, compared to the national average of one in 1,610. But things are improving. “We’re on the right path,” Katz says now. “We still have a long ways to walk.

[widgets_on_pages id=”Crime-2016″]