What Aaron Driver taught us about terrorism and the RCMP

The Ministry of Public Safety takes the lead from the RCMP

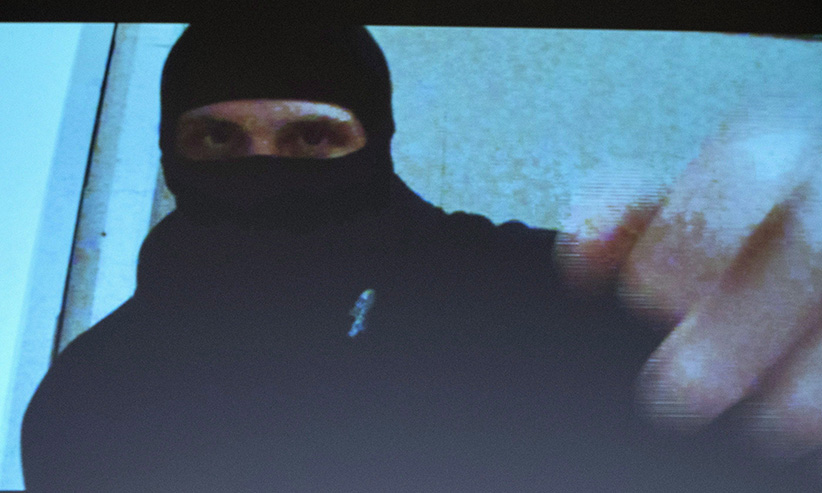

Aaron Driver switches off his video camera in a screen capture of a recording seen during a press conference for what the RCMP are calling a terrorism incident, in Strathroy, Ontario yesterday, on Thursday, Aug. 11, 2016 in Ottawa. (Justin Tang/CP)

Share

In showing that chilling video of Aaron Driver, clad in a black balaclava, on a big screen at the force’s Ottawa headquarters, above the heads of two grim-faced senior Mounties, the RCMP’s message was clear: This is what homegrown terrorism looks and sounds like, and Canadians should be thankful that fast, smart police work stopped him from carrying out his murderous plan.

But another point could also be taken from the story of Driver’s death on Aug. 10 in Strathroy, Ont., killed by a police bullet after the 24-year-old self-proclaimed ISIS supporter set off a homemade explosive device in the back of a taxi. In fact, Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale wasted no time making it: “The government of Canada has to get far more proactive on the whole issue of outreach, community engagement, counter-radicalization, determining how and in what means the right positive constructive influences can be brought to bear to change what otherwise would be dangerous behaviour.”

Within days he was visiting a Montreal centre that tries to help parents who fear their sons are being drawn to violent ideas, like Driver’s embrace of radical Islam. Goodale announced that he will soon appoint an adviser on the issue, and later set up a counter-radicalization office. What Goodale didn’t spell out was that by assuming the lead on this long-overdue push, his department appears to be taking over where the RCMP has failed to make visible progress.

The federal police force has been touting its work on countering violent extremism for a few years. In late 2014, Mounties said a landmark program would be rolled out in early 2015. The basic concept was to support “hubs” where RCMP officers would work with groups of social agencies, religious leaders and community groups to intervene when radicalized individuals looked to be heading toward violence. But no big national launch ever happened.

RELATED: What led Aaron Driver to terrorism?

In its official plan for 2015-16, the RCMP promised to “implement a Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) program,” but the 2016-17 version of the same planning document pledged only to “allocate resources to develop a formal community-based prevention program to address violent extremism.” The force wouldn’t make an officer available for an interview about this apparent back-to-the-drawing-board step, but said by email it has “a number of mutually reinforcing initiatives to help reduce the risk of radicalization to violence” and “has been and will continue to be engaged in discussions around” Goodale’s new centre.

Several independent experts on violent extremism said the RCMP faltered on the file. “They’ve really struggled on this stuff,” said Larry Brooks, who retired from the Canadian Security Intelligence Service in 2014 as its director general of Middle East and Africa operations, and has more recently advised Public Safety on counter-radicalization. One problem, Brooks said, is that the RCMP tends to want to run things, and counter-radicalization programs are generally better spearheaded by street-level agencies.

Lorne Dawson, a University of Waterloo sociology professor and co-founder of the Canadian Network for Research on Terrorism, Security and Society, credited RCMP officers with “really diving into the research” and talking to top outside experts. In the end, though, Dawson said those efforts “just stalled.” He added that Goodale’s initiative, which fulfills a Liberal campaign promise, changes everything. “It’s a total new game,” Dawson said. “So the RCMP activity, I’m sure, has gotten subsumed under it.”

That might be just as well. The RCMP hasn’t always seemed comfortable with what’s sometimes called the “soft side” of fighting terrorism. For instance, the RCMP co-operated with Muslim groups in Winnipeg in 2014 on writing a counter-radicalization handbook called United Against Terrorism, but then withdrew support at the last minute. The RCMP faulted its tone as “adversarial,” though without specifying how. (The handbook did advise Muslims that co-operating with police in Canada is voluntary.)

Sara Thompson, a criminology professor at Ryerson University in Toronto, said the RCMP is likely waiting now to see what steps Goodale’s new counter-radicalization office takes. But Thompson, whose research focuses on youth radicalization, added that police at the local level, sometimes including the RCMP, are already pursuing the promising “hub” approach in dozens of Canadian cities.

The model involves police, social service agencies, community groups, and others, meeting to coordinate interventions when signs point to a risk of violence. It works not just for terrorism, Thompson says, but other sorts of crime, too. “It’s really imperative that the effort play out at the local level and really be controlled at the local level,” she said.

Still, Thompson said Ottawa could play a key role financing these local programs, and funding research into what works and what doesn’t. That could be a job description for Goodale’s new national office, with the RCMP relegated to a supporting role that’s yet to be determined.