A reader’s guide to the Air India bombing and the bloody conflict that preceded it

From the archives: These eight stories from the Maclean’s archive dating back to 1982 help explain the background to Canada’s deadliest terror attack

Share

The debate about NDP leader Jagmeet Singh’s views on Talwinder Singh Parmar, the mastermind of the 1985 Air India bombing, as well as Singh’s appearance at Sikh independence events where extremist views were on display, continues to unfold. Yet to a whole generation the Air India bombing, and the deadly events that preceded it, happened too long ago to be even a distant memory.

Here then, in reverse chronological order, are excerpts from the Maclean’s archives on the terror attack that claimed the lives of more than 300 people, the assassination of Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards and the bloodbath that followed, as well as the Indian military’s storming of the Golden Temple in 1984 which left 500 dead.

Click on the links for the full articles.

May 28, 2007: Air India: After 22 years, now’s the time for truth

The Air India bombings, which claimed 331 lives, most of them Canadian, almost 22 years ago, has belatedly been called Canada’s 9/11. In truth, it was never close to that. The date, June 23, 1985, is not seared into the nation’s soul. The events of that day snuffed out hundreds of innocent lives and altered the destinies of thousands more, but it neither shook the foundations of government, nor transformed its policies. It was not, in the main, even officially acknowledged as an act of terrorism. The political word “tragedy” seemed safer, somehow. It did not carry the same imperative for a rigorous public examination of the cascade of intelligence failures that allowed two planes to depart Vancouver International Airport with bombs planted in their cargo holds.

The Air India bombings, which claimed 331 lives, most of them Canadian, almost 22 years ago, has belatedly been called Canada’s 9/11. In truth, it was never close to that. The date, June 23, 1985, is not seared into the nation’s soul. The events of that day snuffed out hundreds of innocent lives and altered the destinies of thousands more, but it neither shook the foundations of government, nor transformed its policies. It was not, in the main, even officially acknowledged as an act of terrorism. The political word “tragedy” seemed safer, somehow. It did not carry the same imperative for a rigorous public examination of the cascade of intelligence failures that allowed two planes to depart Vancouver International Airport with bombs planted in their cargo holds.

It is only now, in an Ottawa hearing room, that retired Supreme Court justice John Major has a mandate to probe the past—after key players have died and memories have been dimmed by time. For all that, the revelations that have rocked the hearing in recent weeks prove the merits of revisiting the disaster. As well, documents made public by the inquiry, and combed through by Maclean’s, point to a tragic series of miscues, and disastrous false assumptions. They convey a cumulative, powerful impression that the worst terrorist attack in Canadian history might have been averted if clear warnings, repeated over several months, had been heeded.

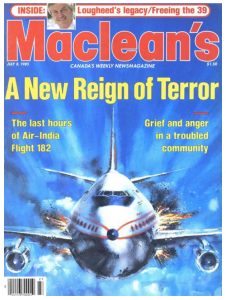

July 8, 1985: The last hours of Air India Flight 182

During a scheduled stopover at Mirabel International Airport, 45 km northwest of Montreal, three suitcases were held after examination by electronic sensors in the airport’s cargo marshalling area. A private security guard took the baggage to a decompression chamber, where it was checked the next day and declared harmless by a Quebec provincial police bomb disposal unit. But because there had been no specific security concerns about the flight, Air India officials were not required to notify Transport Canada of the incident. According to Mazankowski, if his department had been informed that suspicious bags were seized, the flight would have been held until all of the luggage had been searched.

Instead, the gleaming white Boeing 747 with red markings—the slogan “A place in the sky” near its tail—was allowed to leave Mirabel on the second leg of its 15,500-km, 15 1/2-hour journey to Bombay. Inside the cabin the decor would have reminded many passengers of their Indian homeland. Gold paisley curtains separated various sections of the plane and on the walls were paintings of Indian village life. After the airliner reached its cruising altitude of 31,000 feet, flight attendants in multicolored silk saris offered economy-class passengers a choice of meals: chicken curry, lamb in cream sauce or, for vegetarians, rice pilaf with spiced vegetables. First-class travellers chose from a menu of lobster in cheese sauce, breaded lamb cutlet with mint jelly or quails in sauce with poori—fried Indian bread. Passengers were also offered a choice of three movies: Far Pavilions, Phar Lap or Rajnigandaha, a popular Indian romantic film. Then, about an hour before the plane was due to land in London for refuelling, pilot H.S. Narendra, 56, with 35 years of flying experience, radioed the air-traffic control centre at Shannon. The jet was cruising normally, he reported. Behind him, most of the passengers would probably have been dozing and the crew was scheduled to start preparing breakfast.

Instead, the gleaming white Boeing 747 with red markings—the slogan “A place in the sky” near its tail—was allowed to leave Mirabel on the second leg of its 15,500-km, 15 1/2-hour journey to Bombay. Inside the cabin the decor would have reminded many passengers of their Indian homeland. Gold paisley curtains separated various sections of the plane and on the walls were paintings of Indian village life. After the airliner reached its cruising altitude of 31,000 feet, flight attendants in multicolored silk saris offered economy-class passengers a choice of meals: chicken curry, lamb in cream sauce or, for vegetarians, rice pilaf with spiced vegetables. First-class travellers chose from a menu of lobster in cheese sauce, breaded lamb cutlet with mint jelly or quails in sauce with poori—fried Indian bread. Passengers were also offered a choice of three movies: Far Pavilions, Phar Lap or Rajnigandaha, a popular Indian romantic film. Then, about an hour before the plane was due to land in London for refuelling, pilot H.S. Narendra, 56, with 35 years of flying experience, radioed the air-traffic control centre at Shannon. The jet was cruising normally, he reported. Behind him, most of the passengers would probably have been dozing and the crew was scheduled to start preparing breakfast.

Then, at 8:13 a.m. local time (3:13 a.m. EDT) Flight 182 disappeared from the radar screens at Shannon. Just before that happened, said Canadian investigator Art LaFlamme, there was a second radio communication with Shannon exactly eight minutes after the previous one. On it, he said, could be heard the sounds of “rattling, banging and shrieks or howls.” Added one of the controllers later: “There was a frightening feeling. We have never had anything like this before.”

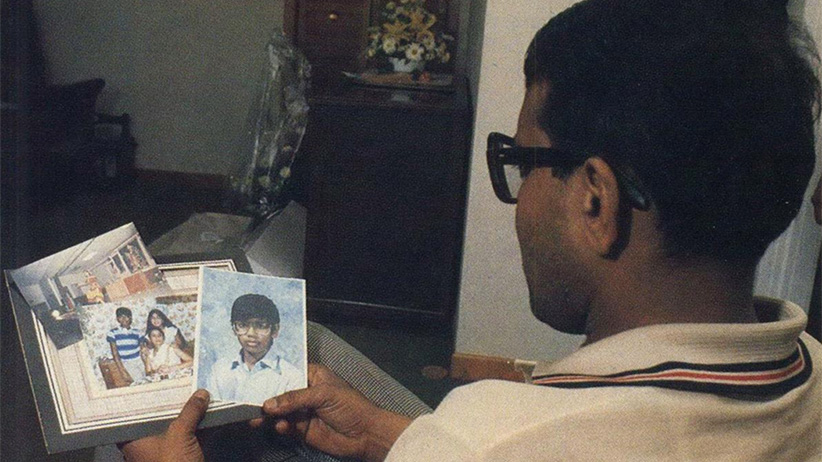

July 8, 1985: The agony of those who waited

At that same service, while a Hindu priest chanted Sanskrit prayers seeking peace for the 50 dead—half of them children—from his 800-family congregation, 45-year-old Scarborough, Ont., accountant Lakshminarayana Turlapati wept for his two sons, Deepak, 11, and Sanjay, 14, who had planned to spend a month with grandparents in New Delhi. Both carried photographs of life in Canada as well as academic and athletic awards they had won since leaving India three years ago. Sanjay, said his mother, Padmini, who practises paediatrics in Newfoundland and came to Toronto’s Lester B. Pearson International Airport to see her sons off, also took along a prize-winning poem he had written. Its title: Death Be Not Proud. Among other parents who awoke that Sunday morning to find themselves without families was Firestone Tire employee Parshotam Dhunna, who had sent his two-year-old son, Suneal, back to his Punjab home for a ritual Hindu haircutting ceremony. Another son, Rajesh, 15, daughter Shashi, 16, Rani, Dhunna’s wife of 18 years, and his 62year-old mother-in-law, Nasib Manjamia, also perished. “All of them,” concluded Dhunna, behind the drawn curtains of a Hamilton, Ont., home full of barefoot mourners. “My wife, my little baby, my son, my daughter. Everything is black. Who should I blame?”

July 8, 1985: A Canadian minority in turmoil

Some 200,000 Canadians trace their roots to the Indian subcontinent. For many of them, the troubles they hoped to leave behind continue to haunt their new lives in Canada. Others, however, have found Canada a fruitful staging ground for political protest and activism. For decades Canada’s Indian immigrants enjoyed the benefits of a society that valued their skills, rewarded their industry—and respected their varied cultural backgrounds. Often highly educated and ambitious for themselves and their children, they settled in cities and towns across the country, moving quickly into professional and white-collar jobs. Montreal’s Concordia University alone lost two professors and three students on Flight 182.

Between 1971 and 1981 the nation’s Indo-Pakistani population skyrocketed to 121,445 from 52,100. The newcomers retained their traditional ties to India—and many of them nurtured passionate political feelings as well. For many Sikh immigrants those feelings were rooted in the long-standing grievances of India’s Sikh population against the Indian government.

. . .

For Sikhs the world over, the assault on the Golden Temple was an act of sacrilege. The raid stunned Canadian Sikhs and sparked demonstrations across the country. But Gandhi’s assassination at the hands of her two Sikh bodyguards five months later shattered the mood of solidarity. Most Sikhs condemned the act as the work of fanatics; still, the bloody anti-Sikh riots that broke out across India after the assassination refuelled the anger of many. Despite recent efforts by Rajiv Gandhi, who succeeded his mother as prime minister, to begin a political dialogue with moderate Sikhs, a wave of terrorist bombings has claimed nearly 100 lives.

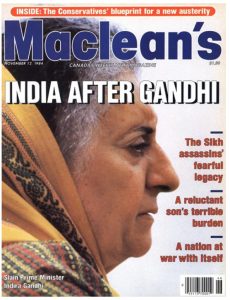

Nov. 12, 1984: India after Indira Gandhi

Gandhi herself had seemed to prophesize her death only hours before the assassins’ bullets cut her down. At a campaign rally the previous night in Orissa state, the prime minister had confided to supporters: “I don’t mind if my life goes in the service of the nation. If I die today, every drop of my blood will invigorate the nation.”

The next morning Gandhi awoke to the sound of chirping parakeets in the leafy compound surrounding her official residence in one of New Delhi’s most elegant areas. In the lush gardens a short distance from the house, actor Peter Ustinov, a cameraman and a producer arrived at 8:30 and began setting up their equipment to interview the prime minister for an Irish television program sponsored by UNICEF. Said Ustinov: “The tea had already been set up, the mike was in place, and we were all ready. We told the press secretary, and he went to fetch her.” Then, dressed in an orange-colored cotton sari, a smiling Gandhi left her house and began strolling toward the television crew.

The next morning Gandhi awoke to the sound of chirping parakeets in the leafy compound surrounding her official residence in one of New Delhi’s most elegant areas. In the lush gardens a short distance from the house, actor Peter Ustinov, a cameraman and a producer arrived at 8:30 and began setting up their equipment to interview the prime minister for an Irish television program sponsored by UNICEF. Said Ustinov: “The tea had already been set up, the mike was in place, and we were all ready. We told the press secretary, and he went to fetch her.” Then, dressed in an orange-colored cotton sari, a smiling Gandhi left her house and began strolling toward the television crew.

. . .

Even the tide of sorrow that swept the subcontinent in the wake of Gandhi’s cremation could not extinguish the flames of sectarian hatred that followed her death. Across the country there was an orgy of arson, looting and lynchings. By week’s end, the death toll had reached 1,000 as furious Hindus took revenge on members of India’s minority Sikh sect, whom they blamed for the murder of India’s third prime minister. Gandhi, who dominated Indian politics for 15 of the past 18 years, fell victim to the very men who had been entrusted with her personal safety. Militant Sikhs claimed that the killing was in retaliation for an assault by government troops last June on extremists occupying Sikhdom’s holiest shrine, the Golden Temple, in the Punjabi city of Amritsar.

Nov. 12, 1984: The world’s divided Sikhs

In one English village they lit fireworks and handed out toffee candy. Outside the Indian consulate in New York they danced and drank champagne. But while militant Sikhs around the world rejoiced last week at the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, more moderate Sikh communities voiced regret over her death and abhorrence at the violence that followed it. Indeed, as India plunged into mourning, Sikhs reacted to her slaying with characteristic ambivalence. In New Delhi the five high priests of Sikhism condemned Gandhi’s shooting by two Sikh bodyguards. And in Vancouver, Jaswan Mangat, head of the International Punjabi Forum, declared, “It’s a matter of shame for all of us to find solutions to our economic and political problems through violence.”

June 18, 1984: The Golden Temple falls

As 450 Sikh militants in the Punjab region of northwest India last week barricaded themselves in the Golden Temple, the religious centre in the holy city of Amritsar, crack government troops ringed the 72-acre complex, demanding that the rebels surrender. But the extremists—led by the fanatical fundamentalist Sant (holy man) Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale—refused, exchanging gunfire with the troops. As a result, the troops stormed the temple complex in a hail of mortar, missile and machine-gun fire. When the rebels waved improvised white flags in surrender five hours later, as many as 500 people had died in hand-to-hand combat, among them Bhindranwale.

As 450 Sikh militants in the Punjab region of northwest India last week barricaded themselves in the Golden Temple, the religious centre in the holy city of Amritsar, crack government troops ringed the 72-acre complex, demanding that the rebels surrender. But the extremists—led by the fanatical fundamentalist Sant (holy man) Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale—refused, exchanging gunfire with the troops. As a result, the troops stormed the temple complex in a hail of mortar, missile and machine-gun fire. When the rebels waved improvised white flags in surrender five hours later, as many as 500 people had died in hand-to-hand combat, among them Bhindranwale.

. . .

Last week some observers in New Delhi predicted that what Sikh extremists were already describing as the 38-year old Bhindranwale’s “martyrdom” might advance the militants’ cause. Certainly, he had presented his coreligionists with a compelling image as a zealot and he was frequently compared to Iran’s Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Inside the Golden Temple he challenged Gandhi to order an attack on the shrine, calculating that the prime minister would hesitate to do so because 17 per cent of the Indian army’s forces are Sikhs. But he also promised a bloodbath if she did. Only days before his death he said, “We may be killed, but a Sikh never weeps.” Observers now suggest that unless Gandhi quickly reopens talks with moderate Sikhs, the battle of the Golden Temple will likely prove to be only one episode in a long war of Sikh independence.

Nov. 15, 1982: The quest for a Sikh state

Sikhs, identifiable by their turbans and kirpans (swords), are a 500-yearold splinter group of the Hindus, born out of the need for an aggressive fraternal army to battle northern conquerors. Although the two sects have rarely come to blows, they differ radically in ethics and ideology. Because the country and the state of Punjab are governed by Hindus, some Sikhs feel misrepresented and claim to suffer from Hindu “imperialism.” Although Sikhs make up only two per cent of the population in India, they predominate in the Punjab. A group of moderate Sikhs, the Akali Dal, have been holding painstaking negotiations with Prime Minister Indira Gandhi since 1974 on a set of 45 secular and religious reforms that would essentially turn the Punjab into a Sikh state. They want more industry, more tax concessions and the right to sell grain at world prices (the central government now keeps prices artificially low). They also want Amritsar to be declared a holy city and the name of the trans-Punjabi train to be changed from the Daily Mail to the Golden Temple.

The Akali Dal has pressed for greater political independence within India, but the radical Dal Khalsa favors complete separation. It seeks to turn the Punjab into a fundamentalist religious country for all Sikhs, to be called Khalistan. Says Gajender Singh, a leader of the radicals, who are mostly young men from rural communities with little formal education: “Like the PLO, we are seeking international recognition and we are prepared to use terror, the political language of the 20th century.”