Bringing Canada’s role in Iraq into focus

War is war, and we’ve been in one ever since Canadian forces arrived in Iraq months ago, writes Michael Petrou

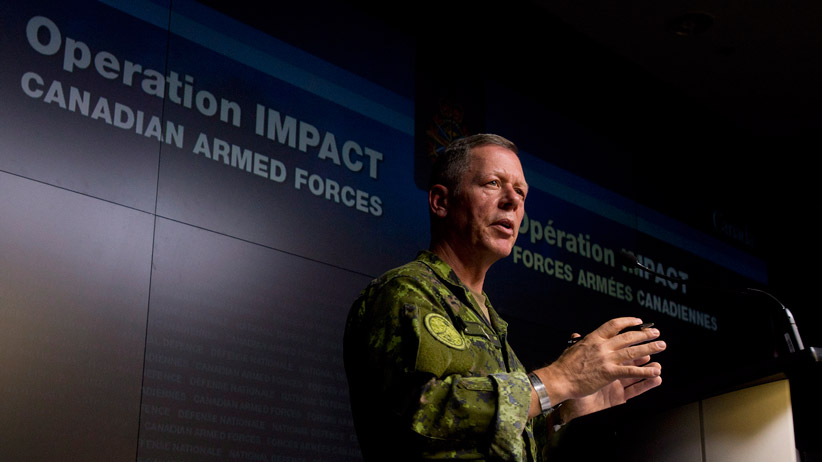

Commander of Canadian Joint Operations, Lieutenant-General Jonathan Vance, speaks during a technical briefing, Monday, January 19, 2015 (Adrian Wyld/CP)

Share

News Monday that Canadian special forces soldiers in Iraq were recently involved in a firefight with the Islamic State militant group should not come as a surprise—despite government claims made when it deployed Canadian troops that they would do no such thing.

Maclean’s visited several frontline positions in Iraq late last year, outposts held by Kurdish peshmerga soldiers confronting Islamic State. In places, Islamic State vehicles and fortified positions could be seen 500 m to a kilometre away, well within mortar or even rifle range. French and American soldiers had recently been to these same outposts, a Kurdish commander said.

The French and Americans are part of the same international coalition as Canada, and they’re ostensibly playing the same “non-combat” role on the ground as Canadian special forces. The Kurdish commander, however, said they were there to pick targets for coalition air strikes, something that would certainly feel like combat for those on the receiving end of them.

Now we know Canadian troops have been doing similar work. Brigadier-General Mike Rouleau, commander of Canadian Special Operations Forces Command, told reporters that Canadian soldiers have called in air strikes 13 times in the past two months. This process can involve getting close to the target to “mark” it with a laser—near enough, in other words, to be shot or shelled by those about to be bombed.

Related: Inside Canada’s new war

Rouleau said the Canadian soldiers involved in the firefight had come to the front to “visualize” a plan they had discussed with their Iraqi counterparts, and then came under “immediate and effective mortar and machine-gun fire.” The Canadians responded with sniper fire and “neutralized” the threat.

It takes some tricky rhetorical gymnastics to describe this as anything other than ground combat, but Jason MacDonald, a spokesman for Prime Minister Stephen Harper, gave it his best shot. “A combat role is one in which our troops advance and themselves seek to engage the enemy physically, aggressively and directly,” he told several media outlets.

This is balderdash. Canadian soldiers operate on the front lines. They guide bombs that obliterate Islamic State fighters. It was nearly inevitable that they would come under fire eventually. Does it really matter, when we’re defining a mission as a combat one or not, who pulled the trigger first?

Still, one has to almost feel sorry for MacDonald, or for whomever wrote the lines he delivered. There’s always been a certain amount of incoherence involved in the framing of Canada’s Iraq mission. Canadian ground troops would not be involved in “direct” combat, Harper told the House of Commons last September. But how is calling in air strikes any less “direct” than spotting for artillery, or firing the guns themselves?

The answer, in part, stems from the perception among many Canadians that war has a hierarchy, that a military intervention involving only air strikes is less consequential than one consisting of ground troops, too—especially if those soldiers are actually shouldering rifles and shooting them. It’s true that air campaigns are generally safer for the Canadians involved. But they can also make a war seem less gruesome and therefore more palatable—at least for politicians voting on a mission, and for the broader public watching and passing judgment from afar.

These are false distinctions. Air strikes may appear like a less intimate method of engaging with the enemy than a bayonet charge, but the effects on the ground are more or less the same. War is war. Canada’s been in one ever since it sent CF-18s and special forces “trainers” to Iraq months ago. This firefight should at least bring that reality into sharper focus.