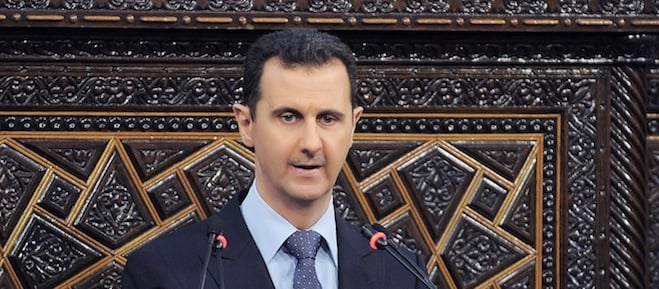

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s summer of defections

Pillars have been crumbling steadily under Syrian President Bashar al-Assad

FILE – This June 3, 2012 file photo released by the Syrian official news agency SANA, Syrian President Bashar Assad delivers a speech at the parliament in Damascus, Syria. Arab countries on Wednesday, Aug. 1, 2012 pushed ahead with a symbolic U.N. General Assembly resolution that tells Assad to resign and turn over power to a transitional government. It also demands that the Syrian army stop its shelling and helicopter attacks and withdraw to its barracks. A vote is set for Friday morning. (AP Photo/SANA, File)

Share

A dictator’s hold on power rests on several pillars. He needs the support of a sizeable chunk of the population, or failing that, he needs its fear. He needs the loyalty of the army and security services. And he must have control of the media—primarily so people will either love or fear him.

These pillars have been crumbling steadily under Syrian President Bashar al-Assad since an uprising against his rule began more than a year ago.

When he responded to protests with deadly force, demonstrators did not back down. They were no longer afraid. He could rely on the army for a time; the first defections were mostly of low-rank soldiers. But these have increased in number and importance. In July, Manaf Tlass, a former brigadier general and member of Assad’s inner circle, joined the opposition. Riad Hijab, Syria’s newly appointed prime minister, defected in August.

This summer Assad also lost the voice of his regime. Ola Abbas spent 15 years as a broadcaster on Syrian state television and radio. Her job of late was to tell her audience that there was no revolution, only armed gangs, terrorists and Western plots. She didn’t believe it, she says, but was afraid. A colleague who filmed a pro-Assad demonstration and showed that hardly anyone attended was taken away and not seen again. But eventually seeing images of massacred women and children compelled Abbas to act. In July she posted a defiant message on her Facebook page and fled Syria for Beirut. She’s now living in a tiny, barely furnished room in Paris, where she was interviewed by the German newsmagazine, Der Spiegel.

Abbas said she often cried in her car on the way to work, tormented by the thought of lying for the regime. She said the presidential palace ultimately dictated the content of her reports, and she often encountered the information minister strolling the station’s hallways.

A member of the same Alawite sect of Islam to which Assad belongs, and which has benefited under his rule, Abbas left behind most of her life when she defected. Both her mother and fiancé support the government. But she felt compelled to choose between her security and her conscience.

“At a certain point, everyone has to decide between the devil and the angels,” she said. “I did it, even if it was a little too late.”

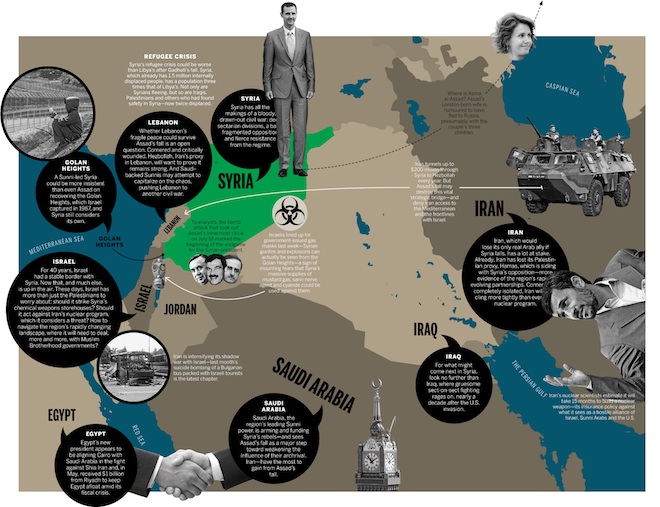

We made this infographic last month to illustrate the ripple effects of instability in Syria in the Middle East and beyond. Click on the image below to open up the full-size graphic: