‘God will provide.’ The life and legacy of Mother Teresa

From the archives: Even before her death in Calcutta in 1997, she seemed destined for official canonization

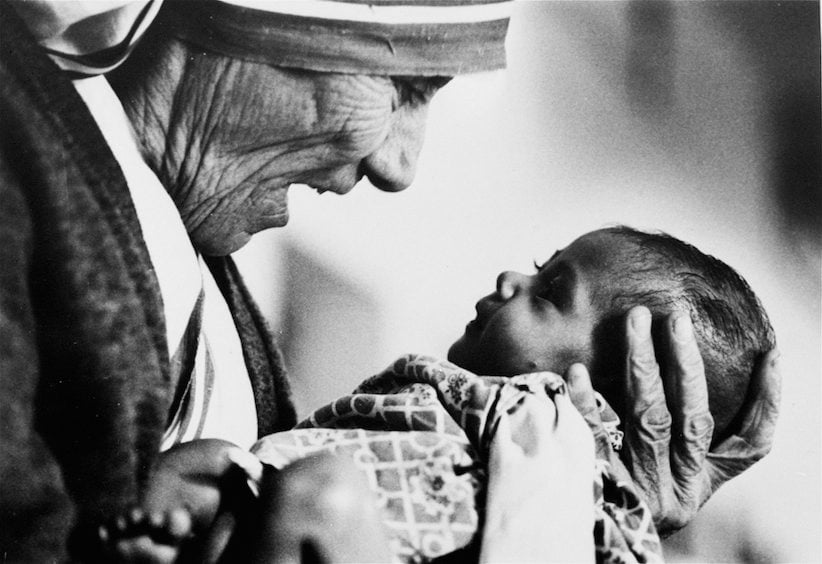

Mother Teresa reaches out to bless a young baby during a stop at Casa San Martin, a feeding place for the homeless in Gallup, New Mexico, May 27, 1988. (Jeff Robbins/AP)

Share

Pope Francis has announced that Mother Teresa will be named a saint on Sept. 4, 2016. In the days after the death of the Albanian nun, Marci McDonald reported on her mission and service in the face of controversy and critics:

Scores of mourners slipped past police to run beside the jasmine garlanded carriage that bore Mother Teresa to her funeral Mass in Calcutta on Saturday, eight days after she died of a heart attack at 87.

Mother, as she was known, was transported on the same gun carriage used in the funerals of India’s founding leaders

Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. Prime Minister Jean Chrétien’s wife, Aline, represented Canada at the state funeral, while Hillary

Clinton represented the United States — both laying wreaths at the

side of the open coffin in an indoor stadium.

‘‘Perhaps the greatest message she has given is the value and dignity of human life,’’ the Archbishop of Calcutta, Henry D’Souza, said in a eulogy heard by 12,000 mourners and a global television audience.

Cardinal Angelo Sodano, speaking in the name of the Pope, praised Mother Teresa for showing love and compassion to the poor while others simply debated how to help them. ‘‘At the close of a century that has known terrible extremes of darkness, the light of conscience has not been altogether extinguished,’’ he declared. The government’s decision to put the military in charge of the funeral of a Nobel Peace Prize winner caused controversy in India, as did her burial in a crypt in the basement of Mother House, the four-storey relief centre tucked behind a crowded alley of the city—removed from the poor she served.

Other Catholics said she should be buried where all could easily visit the grave. Although Mother Teresa had taken a vow of poverty, those who knew her said she would have viewed the pomp surrounding her death as a tribute to the poor. She had defied death so often that when it finally came, even some of her closest followers at first hoped it was yet another false alarm.

‘SHE ILLUMINATED THE GREATEST PROBLEM’

To many, mere mortality seemed out of the question for Mother Teresa, the 87-year-old Albanian nun long hailed as a living saint for her ministry to the impoverished, the leprous and the dying in Calcutta’s teeming, fetid streets.

Even before her death last week of cardiac arrest at her convent in Calcutta, she seemed destined for official canonization by the Roman Catholic Church, for which she had become a wizened 20th-century icon.

‘‘Her importance is that she illuminated the greatest problem we have in the world today—poverty,’’ said Ann Petrie, the Windsor-born director whose acclaimed 1986 film on Mother Teresa has been shown in more than 80 nations. ‘‘And she taught us what to do about it: to spiritualize it—to see the God within each person. Rather than regarding the poor as a problem, she saw every human being, no matter how wretched, as an opportunity to do something for Jesus.’‘

UNQUESTIONING FAITH

Born Agnes Gonxha Bojaxhiu, Mother Teresa was an apparently simple woman who managed to build a complex international order of 4,500 sisters and brothers in more than 100 countries. She did so with a mixture of stubborn entrepreneurial shrewdness—and the fatalism of an unquestioning faith.

Last November, 46 years after she had rescued her first dying outcast from an Indian gutter, Mother Teresa declared herself ready to die when she was rushed to a private Calcutta hospital for the third time that year with heart failure. But again she recovered—and was forced to admit that God appeared to have other plans for her. Throughout the year, she continued with her work, which included a two-month world tour during which she met Diana, the Princess of Wales—a great admirer—for the fourth time, in New York City. But her health remained precarious.

For that reason, the day before her death, her order, the Missionaries of Charity, issued a statement that she would not be able to attend the princess’s funeral. Early Friday evening, after a dinner of soup and toast, she finished her prayers and then complained of pain in her back. A doctor was summoned—even as a crowd began to swell in front of the order’s headquarters. An hour later, nuns rang the huge metal bell outside the main entrance and announced that Mother Teresa was dead.

The accolades that poured in from around the world signalled the great esteem in which she had been held. In Rome, a spokesman for Pope John Paul II said that the pontiff was ‘‘deeply moved and pained’’ by her death. ‘‘She is a woman who has left her mark on the history of this century,’’ the Vatican said.

Others expressed similar sentiments. U.S. president Bill Clinton, on vacation at Martha’s Vineyard, Mass., called her ‘‘an incredible person.’’ In a statement, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien said she was a ‘‘truly exceptional human being,’’ and added, ‘‘Her dedication and courage earned her praise from the mighty and the famous, but it was service to the weak and nameless that gave meaning to her life and for which she will always be remembered.’’ And in London, only hours after her televised tribute to Diana, Queen Elizabeth praised Mother Teresa‘s ’‘untiring devotion to the poor and destitute of all religions.’‘ She will, the Queen said, ‘‘continue to live in the hearts of all those who have been touched by her selfless work.’‘

While the world lauded her accomplishments, including the 1979 Nobel Peace Prize, the Missionaries of Charity mourned the indefatigable woman they called simply ‘‘Mother’‘— and pondered the uncertain future of their order.

Last March, when Mother Teresa voluntarily stepped down as superior general, they elected a successor: Sister Nirmala, a former Hindu who converted to Roman Catholicism. But many observers have questioned whether an order so closely associated with its founder—one who exerted a tight control over her followers that seemed to reflect an earlier era when convent life was more authoritarian and restrictive—can continue to attract new converts and financial support now that she is gone. The missionaries will also debate whether to continue to embrace Mother Teresa’s religious and political conservatism, including a fierce opposition to birth control in one of the most populous countries on earth. Some sisters had also criticized her emphasis on administering to the poor on a day-to-day basis rather than working to change society.

Mother Teresa had always preferred to reach out on a spiritual, not political, level. ‘‘I am not trying to change anything,’’ she said. ‘‘I am only trying to live my love. Let us do something beautiful for God.’‘

That devotion had informed her decisions ever since she accepted her call to the religious life at 18 in Skopje—now in Macedonia—where she grew up the youngest of three children born to a prosperous contractor and importer. After her father died when she was 9, the family lost its money and her mother, forced to take in sewing, became even more devout in her own Catholic faith. Taking young Agnes on her rounds visiting the sick and needy, she helped inspire her daughter’s later vocation. But enraptured by classroom tales of missionaries in India, Agnes set her heart on joining the Irish order of the Sisters of Loreto, known for their work there.

THE ‘CALL WITHIN A CALL’

At 18, after two months at their Dublin headquarters, she set sail to teach history and geography at St. Mary’s, the order’s high school for girls in Calcutta, where she later became principal—and ultimately an Indian citizen.

In Petrie’s film, the Loreto nuns seem at pains to insist that during her two decades with them, Sister Teresa, as she was known, showed neither exceptional intelligence nor unusual promise. But unlike others in the convent’s oasis of manicured gardens, she looked out her bedroom window and could not resign herself to the tableau of human misery unfolding daily in the slums of Calcutta.

On September 10, 1946, while travelling by train to a retreat in the mountains of Darjeeling, she received what she termed her ‘‘call within a call’‘—to work with the poorest of the poor. Four years

later, after her implacable efforts finally won her an exceptional

papal order of ‘‘uncloistering’‘—allowing her to work independently—she set out into the city streets with only three months’ medical training, no money or plan—but with the phrase that would become her guiding dogma: ‘‘God will provide.’‘

Given the honors since heaped upon her, it seems difficult to grasp her difficult beginnings. Attempting to set up an outdoor school in

a vacant lot, writing the letters of the Bengali alphabet in the

mud, she found herself taunted and stoned, accused by Hindus of trying to convert the helpless to Christianity. But in 1952, the city donated a former hostel near a temple to Kali—the Hindu goddess of death and destruction—as her first home for the dying, Nirmal Hriday (Pure Heart).

And after she took in one of the sect’s priests, who had been expelled from the temple with leprosy and left in the streets to die, the hostility suddenly evaporated. That year, as the Vatican officially sanctioned her new order, begun with a handful of former students outfitted in simple saris of white homespun cotton edged in blue, her reputation began to spread. With her order originally restricted to women, she insisted that her sisters take the three traditional vows of all nuns— poverty, chastity and obedience. But she added a rigorous fourth— “to give wholeheartedly, free service to the very poorest”—and demanded that the sisters themselves live in poverty with only a single change of clothes and minimal possessions, including a scrub brush and bucket.

In the 1980s, after supporters turned over a lavishly refurbished headquarters in San Francisco to the order, Mother Teresa thanked them politely, then promptly went in and tore up all the expensive carpeting, pews and water heaters that had been newly installed, insisting that her nuns live equally everywhere in the world.

When Malcolm Muggeridge, the cantankerous British pundit, first met her in 1969, he found himself awestruck, reporting ‘‘a shining quality.’’ As he later wrote, ‘‘I never met anyone more memorable.’‘ Petrie concurred: ‘‘Her presence is astonishing.’’

But over the years, Mother Teresa consistently countered attempts to sentimentalize her with canny single-mindedness in the pursuit of her work. In 1964, Pope Paul VI bestowed on her a white Lincoln limousine that had been presented to him during a congress in Bombay. She promptly raffled it off—and with the nearly $100,000 in proceeds, opened Shantinagar, her village for lepers. And when the Indian government gave her a free rail pass, she badgered them for the same privileges on its airline, gamely offering to work off her passage as a flight attendant.

In Guatemala, the governing junta threatened to expropriate her prime inner-city mission for a shopping mall, but she doggedly declined their offers of other lots. And during filming, Petrie watched bemused as Mother Teresa confounded then U.S. envoy to the Middle East Philip Habib when he told her she could not enter West Beirut because of shelling. She calmly responded that she knew there would be a ceasefire: she had been praying to ‘‘Our Lady’’ for that very thing. The next day, a ceasefire was indeed declared, and she entered the rubble with a convoy of four ambulances to rescue dozens of abandoned and handicapped orphans.

‘SOMETIMES THAT’S HOW IT IS’

But while some saw her as a saint, others had less flattering descriptions. In a blistering 1994 television documentary for Britain’s private Channel 4 called Hell’s Angel, and an ensuing 1995 book entitled The Missionary Position, Vanity Fair columnist Christopher Hitchens berated Mother Teresa as a demagogue and a propagandist for the Vatican’s anti-abortion campaign. In elaborate detail, Hitchens chronicled the fact that she had accepted honours from the likes of Michele Duvalier, the wife of Haiti’s former despot Jean-Claude (Baby Doc), and a $1.75-million donation from Charles Keating Jr., an American savings and loan tycoon convicted in 1993 of fraud and racketeering. But she refused to answer the charges. And nearly a decade earlier, in Petrie’s film, she had explained that if ‘‘God takes away your good name, you accept it. If you’re on the street, you accept being in the street. Sometimes that’s how it is—everything is taken away from you.’‘

Now, without her overwhelming presence, her order will find it more difficult to ignore such critiques—or even to reap such publicity and public largesse. And some of her followers are more determined than ever to tackle the root causes of poverty rather than administer Band-Aids. Certainly, whatever direction the Sisters of Charity choose to map, the order will never be the same. Then again, as Petrie points out: ‘‘There will never be another Mother Teresa. But her message remains in the work: she always told people who wanted to come to India to do the work the hard way—to start with their own families. She taught that the poorest countries in the world were not the developing nations but the United States and Canada—because of the lack of love.’’

Briefly, their paths crossed in the CBC’s fourth-floor Toronto waiting room for guests on Newsworld’s Pamela Wallin Live. Tension bristled in the air. Breezing out of the studio in a rumpled blazer and his only tie was Christopher Hitchens, the cheeky Washington-based columnist for The Nation and Vanity Fair, who had just fired off the latest salvos in an unlikely cause—his one-man crusade against a wizened 85-year-old Albanian nun named Agnes Bojaxhiu, better known as Mother Teresa. In a print sequel to his provocative 1994 British television documentary, Hell’s Angel, Hitchens had published a 98-page tirade titled The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and in Practice.

Castigating the woman he had dubbed M.T. as a ‘‘demagogue’’ and a propagandist for the Vatican’s anti-abortion campaign, he charged that she had not hesitated to consort with some of the world’s most notorious dictators or take money from convicted con men.

ENTER LUCINDA VARDEY

Arriving to answer that attack was Lucinda Vardey, a leading

Toronto literary agent turned religious writer who had inadvertently

found herself cast as the defender of one of the most venerated

figures in Christendom. For Vardey—like Hitchens, a 46-year-old

Briton transplanted to North America—the role was both unexpected

and unsought. Last year, shortly after his documentary sparked an international uproar, she received a request from a British

subsidiary of Random House—the same publishing company that brought out the Pope’s best-seller, Crossing the Threshold—to compile a

book with the 1979 Nobel Peace Prize-winner she now refers to simply

as ‘‘Mother.’’

The result is A Simple Path, a pastiche of prayers, inspirational guidance and testimonials from both Mother Teresa and her associates in the Missionaries of Charity, who operate in more than 100 countries around the world.

To Vardey’s discomfiture, she found it rushed to publication on exactly the same day in October that Hitchens’ broadside was being released by Verso, the tiny book division of London’s New Left Review. Refusing to debate him, she had also declined Wallin’s invitation to appear together on camera. But suddenly, as he ambled off the set, they met. The encounter was cordial—and decidedly brief. But then, words alone could never have bridged a philosophical divide as old and unresolvable as religion itself: the chasm between reason and faith.

As Hitchens had admitted at a New York City reading days earlier, his target was larger than Mother Teresa: he had set out ‘‘to prove all religion equally false.’’ A messianic atheist, he acknowledged his fascination with religion, which he called ‘‘one of the great subjects. But I don’t think it’s a force for the good. It’s a very dangerous thing.’’

‘MOTHER DOESN’T JUDGE’

To Vardey, a committed Roman Catholic, their differences came down to a fundamental Christian belief—the notion of a living savior. When Mother Teresa professed to see Christ in every human soul, she made no distinction between a maggot-riddled beggar dying in the streets of Calcutta and Michele Duvalier, the shopaholic wife of the former Haitian dictator known as Baby Doc. ’‘Mother doesn’t judge,’’ Vardey said. ‘‘She doesn’t ask why the money comes or where it comes from. She says it’s for Jesus.’‘

For Vardey, finding herself ensnared in the thorny Mother Teresa debate is an unexpected twist on her own anything-but-simple path. Until a year ago, she had planned to consecrate this fall to launching another book, her sweeping 900-page anthology of postwar spiritual writing called God in All Worlds, published in November by Knopf just two weeks after A Simple Path. Compiled over the past five years, it ranges from selections by Catholic mystic Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, the Hindu Vedas and Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh to Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung, New Age guru Shakti Gawain and raunchy novelist Erica Jong. Culling that eclectic mix required encyclopedic reading. And, as Vardey admits, it is no accident that she organized the passages according to the stages of a spiritual quest. In fact, the book is a milestone on the London-born author’s own spiritual journey, which began in the southeast English village of Fetcham, where she grew up one of five children, and where the tussle between reason and faith was played out in her own family. Her father, a self-taught artist who became art director for Reader’s Digest—and died in November—was a non-Catholic who eschewed religion as ardently as her mother attended Sunday mass.

Vardey recalls spending hours in her grandmother’s bedroom, which resembled ‘‘a kind of sacred grotto’‘—complete with statues of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart dripping blood and a vial of sacred water from Lourdes. But after she attended convent school, the swinging London of the 1960s called. A onetime member of Britain’s National Youth Jazz orchestra, she landed her first job at 17 when she saw an ad for a typist in the window of a publisher near her nightly gig playing jazz piano in Soho. In 1970, she won a posting to Toronto, where she began working as a publicist.

Driven and flamboyant, given to long flowing skirts and floppy hats, she stayed to make her mark on the burgeoning Toronto publishing scene. When John Fowles’s novel Daniel Martin came out in England, she helped to separate out the Canadian from the American rights—a revolutionary notion at the time. In 1977, she founded her own literary agency, and eight years later she set a new record for the business. Bypassing Toronto, she took the manuscript for a spy thriller by an unknown Ottawa peace activist named Anthony Hyde straight to New York, where she won The Red Fox the first million-dollar advance ever awarded to a Canadian writer.

‘‘I knew that if it just came out of Ottawa, Canadian companies would offer me $5,000 for it,’’ she says. ‘‘It was just a case of taking our own for granted.” A tough negotiator, she was also known for her grit. In 1980, when investigative journalist Ian Adams regained the rights to his controversial novel, S: Portrait of a Spy—the object of a $2.2-million libel action by retired RCMP official Leslie James Bennett—he found the book industry wary of him. Although the suit had finally been settled by his former publisher, he was considered too hot to handle until Vardey agreed to take him on.

She conducted an auction and won him nearly $30,000 for the paperback rights. ‘‘No one else would touch me,’’ Adams says.

On the side, Vardey co-authored her own first book, an anthology called Pigs: A Troughful of Treasures, edited by her friend and former client, novelist Barbara Gowdy. ‘‘She put as much passion and perfection into that,’’ Gowdy says, ‘‘as she does into everything.’‘ Every Sunday, some of that passion emerged at a local church, where Vardey doubled as organist and choirmaster. But as a traditionalist, she left after a falling-out over including guitars in the service. Increasingly, she found herself examining her own relations with Catholic orthodoxy.

For five years, she rose at 4:30 a.m. to thrash out that internal debate in the pages of Belonging: A Book for the Questioning Catholic, which was released to mixed reviews in 1988. ‘‘It met the confusion that was then sweeping North America,’’ says her publisher Louise Dennys, a longtime friend. ‘‘It was a very grass-roots book.” But Vardey insists that she never thought of herself as a religious woman.

Then, exhausted and depressed, she was diagnosed with a thyroid tumor. Although benign, its side-effects changed her life. A self-confessed workaholic who had just ended a long-distance relationship in Italy, she was confined to bed for months. ‘‘My life was sell, sell, sell; prove, prove prove,’’ she says. ‘‘Suddenly I was being forced to lie flat on my back and listen to God.’‘ She found unexpected comfort from prayer and a lay healer’s touch, while a series of coincidences prodded her towards a more ecumenical route.

At film director Norman Jewison’s annual garden party, she met Ann Petrie, who had just won an Emmy for a documentary on Mother Teresa and who introduced her to a yoga ashram. There, the Hindu scriptures led her to Buddhist meditation and Gestalt therapy, and finally back to a reconfirmed Catholicism.

Five years ago, on a business trip to New York, Vardey leaped at a chance to come to terms with that eclectic odyssey. Over their usual working lunch, Marty Asher, the publisher of Vintage Books, wondered aloud why, despite the rage for New Age themes, no one had put together a serious spiritual anthology. ‘‘Lucinda sat bolt upright and said, ‘I want to do that book for you,’ ‘’ Asher recalls. ‘‘Suddenly, she revealed this whole other corner of her life I had no idea about.’‘

Vardey was still in the course of her research when she found herself invited to a Toronto dinner for spiritual singles. As she mentioned reading the complete works of Carl Jung and Thomas Merton, she made an unexpected impact on the already-intrigued host, a former seminarian named John Dalla Costa, who had just stepped down as president of his own advertising agency. ‘‘I thought, ‘Wow, here’s someone as obsessive as I am,’ ‘’ he says. ‘‘It might sound strange, but I found it very sexy.’‘

Just as their relationship began, she flew off to Italy, where, within a week, she bought a 600-year-old Tuscan farmhouse near a hermitage once established by St. Francis of Assisi. There, two years later in October, 1994, they were married by a Franciscan priest to the strains of an eighth-century Gregorian chant sung by two choristers imported from Westminster Cathedral. ‘‘It was—it is—a marriage made in heaven,’’ says Dennys. ‘‘It’s a magical story—this extraordinary sharing of interests in the spiritual as well as the business worlds.’’

Agrees Vardey: ‘‘It’s unimaginably wonderful to find someone you can pray with who isn’t a wimp.” But no sooner had they landed home from their honeymoon when her agent phoned with the offer to compile a book on Mother Teresa, presumably a final statement.

FAITH IN ACTION

Many of Vardey’s beliefs—including the importance of making abortion available in certain medical cases—stood at odds with those of her subject. The research trip to India would also prevent her from sharing her first Christmas with her new husband. But in the end, she accepted the job. Learning about Hitchens’s planned attack on her subject was not what motivated her, she says, but it ‘‘was the factor that pushed me to meet the deadline.”

On her first day in Calcutta, she was tickled by her subject’s mix of piety and pragmatism. In the midst of predawn prayers, Mother Teresa noticed someone had left on a light. ‘‘She gathered herself up off the floor to turn it off,’’ Vardey recounts. ‘‘I loved her right there.’’ Her experience at the mission also had a profound personal effect: ‘‘I knew there would be a big lesson in this for me—how I put my faith into action.’‘

Already, last year, she had sold her agency, retaining only a handful of writers—among them Anthony Hyde, Jungian analyst Marion Woodman and Bombay-born novelist Rohinton Mistry, who won this year’s prestigious Giller Prize for Canadian fiction with his second novel, A Fine Balance. ‘‘It was death to continue for me,’’ Vardey says. ‘‘But what rocked a lot of people was that I was changing.’‘

Last month, she and Dalla Costa celebrated those changes by throwing a joint book launching for her anthology and his just-finished appeal for a new set of corporate values, called Working Wisdom (Stoddart). And in a watermelon-red room on the second floor of the airy town house they share, where a statue of the Virgin Mary nestles in the front garden and a Buddha keeps vigil over the back deck, Vardey now offers Gestalt therapy and yoga to a select clientele while building a new stable of writers who concentrate on the spiritual.

As a former marketing whiz, she is not unaware that her own changes mirror a larger spiritual search currently sweeping society. And at a time when more people appear to be turning to faith for answers than reason, Vardey admits that Hitchens’ rationalist attacks have proved an unexpected boon to her books. ‘‘The reaction is more explosive,’’ she says, ‘‘because they’re being reviewed together.’’