Hamid Ghassemi-Shall’s waking nightmare inside an Iranian jail

After 64 months in prison, Toronto man opens up on his ordeal

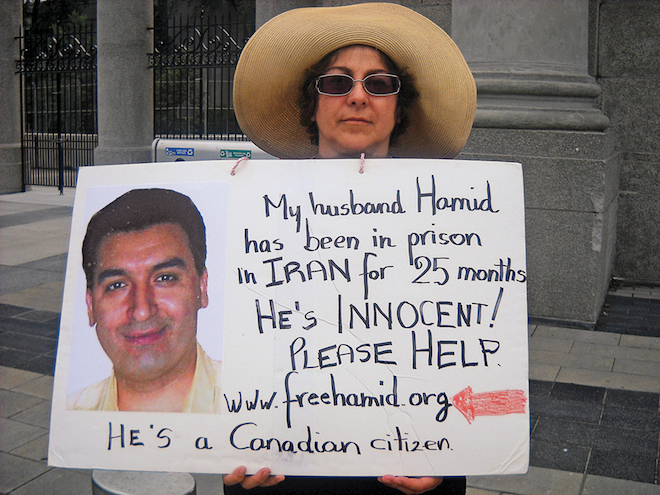

Hamid Ghassemi-Shall (Photo by Anne-Marie Jackson)

Share

Of the four brothers and sisters in his working-class Tehran family, Hamid Ghassemi-Shall was closest to Alborz, his older brother by nine years.

“I grew up in his arms,” he says. “We were mostly together, especially after school. He used to help me with my homework. At night we used to sleep in one bed. He used to tell me stories until I fell asleep.”

It was natural, then, years later in 2008, that when Alborz got into trouble with Iranian authorities, it was Hamid who investigated and tried to make things better.

Hamid had immigrated to Canada some 15 years earlier. He had picked Canada, in part, because he heard it was a multicultural country, home to people from “any culture you can think of. You feel sometimes that you belong somewhere, but you don’t know until you get there. And probably that was my destiny, I would say, to come here. I was homesick for a few months, but after that, it was gone.”

Meeting Antonella Mega soon after he arrived helped. Hamid was working in an Eaton Centre shoe store in Toronto on a busy spring Saturday when she walked in. Antonella had been looking for shoes without success and was feeling irritated. “And then I saw him,” she says of Hamid. “And there was something so special about the way he approached me. And so I said to myself, ‘Okay, be nice to him.’ ”

They started to talk. Hamid guessed, correctly, that she was Italian. Antonella guessed he was from Iran. “I could tell he was new to the country, and he looked like such a nice person,” Antonella says. “And I remembered it was difficult as an immigrant, and I thought, you know, it’s so nice to have friends when you come to the country.”

Within a year they were married. “When you know the person is the right person, hesitation is not an option,” he says.

Antonella still has the shoes Hamid sold her. Cream leather slingbacks. They had been put aside for another customer but Hamid decided to sell them to her anyway.

Hamid frequently returned to Iran to visit his family. He never had reason for concern until 2008, when Alborz was arrested and his house searched. Hamid went to his brother’s home to find out what was going on. While there, he called his mom, who told him officials were at that moment searching her house, too. Among the items they took was Hamid’s Canadian passport.

Hamid went to the Canadian embassy to alert them. He wanted to be sure Iran would not misuse his Canadian passport. “They didn’t treat me like a Canadian citizen,” he says of the embassy staff. He wasn’t even able to get past the locally hired Iranians.

Hamid learned his brother was being held by Iranian army intelligence. An official there told him the problem was related to Alborz’s service in the Iranian navy, from which he had retired two years earlier.

Though he was scheduled to return to Canada shortly, Hamid wanted to stay in Tehran to help Alborz. He needed his Canadian passport to cancel his plane ticket, so he went to army intelligence to retrieve it.

“When I introduced myself, all of a sudden, I saw five guys,” Hamid says. “They surrounded me. They said, ‘We have a few questions for you. It’s going to take about three hours.’ Those three hours became a death sentence, and 64 months in prison.”

Even today, more than five years later, back in the living room of the east Toronto home he shares with Antonella, Hamid does not understand the nightmare he’s been through—one that reflects the arbitrary cruelty of Iranian justice. “I’m looking for answers myself,” he says.

Hamid has been back in Canada for two weeks, a fraction of the time he spent on death row. When he describes those years, his voice is measured and a little quiet. He sits by patio doors wearing a golf shirt neatly tucked into blue jeans and blue rubber sandals over thick socks. He offers tea, coffee, pistachio nuts and green raisins. He speaks for almost four hours about what happened to him. But he doesn’t know why. He can’t explain why he and his brother were arrested, the charges against them, why he was almost hanged and why Alborz died—sick, blind, scared, with a massive brain hemorrhage.

Hamid could not know that any of this was in his future when he was first brought to a detention centre run by military intelligence in 2008. Immediately, his captors placed him in solitary confinement and began their interrogations, hoping to elicit a confession that he was a spy for an unspecified country. The only evidence prosecutors produced, Hamid says, was a forged email from Hamid to Alborz asking for military information.

“They insult you constantly. They’re swearing at you. They’re insulting your family,” he says, describing sessions that took place every day except Fridays, the Muslim day of prayer. “We all have pride. We all have dignity. And when they try to squeeze everything that you’ve got, destroy everything that you’ve got, this is worse than physical torture, I think. You know, when they beat you, they don’t beat you where there is a scar left on your body. They want that you feel the pain, but there is no sign of punches on your body. The pain goes away and you forget. But when they torture you psychologically, it’s with you for the rest of your life. It’s tattooed on your brain and you can’t do anything.”

Hamid’s interrogators told him they would kidnap his sisters, his nephews, even Antonella in Canada, and bring them to the prison. He believed them.

“Anybody does,” he says. “Because when you’re dealing with somebody that is unpredictable, when you haven’t done anything and you’re being charged with espionage, don’t you think they might do it? So that’s the worst torture.”

Almost as bad as the interrogations was the crushing grind of solitary confinement. Hamid spent all but a few minutes each day in a tiny cell, six feet by 10 feet, isolated from his brother, other prisoners, the rest of the world.

“How much can you handle? How much can you tolerate? Sometimes you think probably you’ve done something that you’re not aware of. They drive you to that point, because your brain can only handle so much pressure. Some people, they go crazy. They’re banging their head into the wall. Some people, they try to manage it. They don’t lose their hope. I didn’t lose my hope, most of the time,” he says.

“And you know, the interrogation room is exactly the same size as your cell. They take you from one cell where nobody’s talking to you, and they put you in another cell. There’s a mirror that you see yourself in, and there’s a voice coming from the other side of the glass. And you’re seeing yourself, and you’re talking to yourself. It has a lot of side effects if that person cannot control himself.”

After eight months of solitary confinement, Hamid and Alborz were tried in a revolutionary court. Hamid was allowed 15 minutes with his lawyer first. That’s when he learned the espionage charges had been dropped months earlier. Now he and Alborz were accused of co-operating with the People’s Mujahedeen, an outlawed opposition group that Iran considers a terrorist organization. There were no witnesses. To support this new charge, Hamid says, prosecutors simply altered their original forged email.

Hamid says he has never belonged to the People’s Mujahedeen. He hasn’t been involved in politics at all. Most of his friends in Canada are not Iranian—something his interrogators could not accept, as they demanded to know about his relationships with other émigrés.

“They were chasing a ghost,” Hamid says.

But the judge found the brothers guilty and sentenced them to death. Their lawyer, not wanting to panic them, told them it was life imprisonment.

Hamid and Alborz returned to solitary confinement at the military detention centre for three more months, and were then transferred to solitary confinement at Evin Prison, where Iranian-Canadian journalist Zahra Kazemi was tortured to death in 2003.

During this time, Hamid received only short and sporadic visits from family. They were always supervised, and Hamid was forbidden from talking about his treatment. The visits were bittersweet. “I didn’t want them to see us in that condition, because they could see the signs of the pressure we were gong through,” he says. He wasn’t allowed to see his brother. He couldn’t call Antonella.

“Really, I was in a black hole. I knew nothing,” Antonella says of that time. Mahin, Hamid’s younger sister, would call Antonella to reassure her that she has seen Hamid and that he was okay, but her English was not fluent and it was difficult for Antonella to understand exactly what was happening.

Hamid and Alborz spent 18 months in solitary confinement—first at the military detention centre, then at Evin Prison—and were then transferred to Evin’s general population, section 350, for political prisoners.

There are 11 rooms in that section, and each room has 21 beds. The prison population swelled after the rigged 2009 presidential election and the protests that erupted in its wake. Some prisoners had to sleep on the floor. Still, Hamid says, conditions were much better than in solitary. He and Alborz were together again. He was no longer beaten or insulted. “We had no problems with the guards or the warden. The problem we have is with the justice system,” Hamid says.

When he left solitary confinement, Hamid learned the truth about his sentencing. His lawyer had appealed the sentence months earlier. The Supreme Court rejected the appeal, and Hamid was given written notice. “When I looked at it, I said, ‘Holy God, execution. They told us life,’ ” Hamid recalls. “From that point, it became really hard.”

Hamid tried to prepare himself for death. “I would say to myself, ‘You know, it’s just 10 minutes, it’s gone, it’s finished,’ ” he says. “But the more that you think about it, it’s not a heart attack that you don’t know is going to come. You know the procedure. They’re going to take you away one afternoon. They’re going to put you in solitary. At four o’clock in the morning, they’re going to come after you, and they’re going to take you and they’re going to hang you.

“Every minute of your life there with that sentence is like being in the ocean without a life vest, and you hardly can swim and you just keep going down and up in the water.”

Six of Hamid’s fellow political prisoners were executed during his time at Evin. They would simply be called away—even in the middle of a volleyball game—and the next day, the Justice Department would release a statement announcing the execution.

Most prisoners didn’t dwell on the deaths of other inmates, Hamid says. After a couple of days, they would move on. It was different for prisoners condemned to die. “For those of us on death row, we couldn’t forget. It’s like being hit by a sledgehammer. It just destroys.”

Two weeks after their transfer to Evin’s general population, Hamid and Alborz were temporarily moved back to the military detention centre where they had spent a year in solitary confinement. Alborz, on arriving, suffered a panic attack.

“It’s indescribable how much pressure we went through,” says Hamid. “If they had killed us right on the spot, we wouldn’t have suffered that much.”

Hamid convinced the guards to take Alborz to an army hospital, where they kept him for three days. Meanwhile, Hamid was brought back to an interrogation room and pressured to confess in exchange for a possible reduction in sentencing.

“At that point, I started to fight with them,” he says. “I told them what I should have told them a long time ago. I told them, ‘I don’t want your pity. If you guys have just a little bit of conscience, if you believe in God, go to the judge and explain where you got that piece of paper that you guys fabricated and are claiming to be an email I sent.’ ”

Military intelligence sent Hamid back to Evin. Alborz joined him a couple of days later and said he had been beaten in the hospital. Alborz’s health began to collapse.

In retelling what happened next, Hamid loses his composure slightly for the only time. He tears up, stops talking and tightly clutches Antonella’s hand.

First, Alborz lost his vision. When the prison warden suspected Alborz was faking, Hamid exploded in anger. “I yelled at him. I said, ‘Who in the hell do you think you are? Do you know who this person is who you are treating like this? He served the country for 29 years. He defended the country during the war. If it wasn’t for people like my brother, those Iraqis would probably come and rape your family.’ ”

Alborz went briefly to a hospital, where a specialist said he had stomach cancer but was not psychologically prepared for chemotherapy. The specialist recommended he be allowed to spend some time at home with his family. Instead, Alborz was returned to Hamid’s room in section 350 of Evin. “He didn’t know where he was, how long he had been there. And when I told him we have been in prison for a year and a half, he would cry like a baby,” Hamid says.

One morning, Alborz couldn’t stand up. Hamid told a guard to send for an ambulance. He then put his brother on his back and carried him out of their cell. There was no ambulance waiting, only a pickup truck. The two brothers went to a nearby hospital, but Hamid was not allowed to stay. Four days later, he learned Alborz was dead.

The official autopsy report said he had succumbed to cancer, but a coroner privately told his family that Alborz’s skull was caved inward and that he had suffered a brain hemorrhage.

“I wrote a letter request to the prosecutor that I would like to attend my brother’s funeral, accompanied by guards, just for a few hours to pay my respects,” Hamid says. “They never responded.”

Antonella went 18 months without hearing her husband’s voice. That changed when Hamid left solitary confinement. There was a phone in the prison wing, with allotted time divided among the more than 200 prisoners. Those without families, or whose families didn’t have phones, gave Hamid their minutes. “We just reassured each other that we weren’t going to give up, and that I knew he was innocent,” Antonella says. “I reassured him that I loved him, and I wasn’t going away and that I was going to fight for him.”

Inside, Antonella was suffering. “It was pretty much hell,” she says. “The reality is I didn’t keep my spirits together. There was not one moment in my life that I wasn’t thinking about Hamid. And when Alborz passed away, I sat on this chair for three months. I was paralyzed.”

Antonella lost her job. “Financially, I’m not saying we’re ruined, but we have to find a way to go forward,” she says. Her health declined. And while she received stalwart support from some friends—and strangers—others drifted away.

“There were a lot of people who were afraid to be associated with us. I don’t blame them; not everyone can carry this. And I don’t blame people who couldn’t take it,” she says.

Antonella was initially disappointed in the Canadian government’s response. Officials at Foreign Affairs, she says, refused to speak with her about Hamid without his authorization. Eventually they did, but Antonella feels their efforts were limited. “They felt their job was just sending diplomatic notes,” she says.

Canada did not publicly raise Hamid’s case until January 2011, when then-Foreign Affairs minister Lawrence Cannon issued a statement expressing concern for “the uncertain fate of two Canadians of dual nationality who remain in prison in Iran.” He did not mention Hamid by name but was likely referring to him and blogger Hossein Derakhshan.

Antonella tried other tactics. She applied, unsuccessfully, for an Iranian visa so she could plead Hamid’s case in Tehran. She enlisted the help of Amnesty International, which, following its own investigation, threw its support behind Hamid. And after keeping mostly silent for the first two years of his incarceration, Antonella began speaking to media in 2010 in an effort to build public support for Hamid.

Two years later, in the spring of 2012, Hamid received an unexpected visit from his mother and older sister, Parvin. They had come to tell him that his younger sister, Mahin, had died in hospital. “It was very difficult to handle,” Hamid says.

More sad news followed. Hamid asked the prison judge whether he had new information about his case. “He said, in front of my mom, ‘Your file has arrived here for enforcement.’ It means for doing the execution, the last step,” Hamid says.

Hamid told Antonella, who informed Foreign Affairs. Iran’s chargé d’affaires was summoned to meet with the deputy minister of Foreign Affairs in Ottawa.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper, who was travelling in Chile at the time, publicly warned Iran: “The government of Iran should know that the whole world will be watching, and they will cast judgment if terrible and inappropriate things are done in this case.”

News of these interventions reached Hamid in Evin. He says they were “heartwarming.” “This is the thing that I wanted from the beginning, a statement from the Prime Minister that he is supporting the case, is drawing a red line for the Iranian government, and not to cross that line. You get a lot of hope with that.

“When the highest politician in a country is making a statement for a particular person, of course it’s going to be effective,” Hamid says, adding: “But they could have done more earlier, and probably would get the same results much earlier.”

A month later, the House of Commons passed a unanimous motion calling on Iran to grant Hamid clemency, release him to his family and “reverse its current course and to adhere to its international human rights obligations.” Canada’s diplomatic pressure on Iran increased that fall when Canada shuttered its embassy in Tehran and expelled all Iranian diplomats from Canada.

The closure affected Hamid’s family directly. Hamid says the embassy was a “sanctuary” for them, somewhere they could go to get news and reassurance that he hadn’t been abandoned. But he’s still glad Canada shut it down because of the “clear message” it sent the Iranian government. “I knew they didn’t close down the embassy because of me,” he says. “But I knew my case was part of that closure.”

Hamid was never allowed to meet with Canadian diplomats directly, even when the embassy was open, but he still wanted to thank them for their work. Using the standard prison currency of cigarettes, he hired an artistic inmate to make two intricate dolls out of coloured threads as gifts for a Canadian diplomat with two daughters. He gave the dolls to Parvin to deliver.

The Canadian embassy is also where Parvin got Hamid English reading material in the form of back issues of Maclean’s. By the time these passed through prison censors, none of the articles was redacted. But photos of women with bare skin exposed—including one showing Michelle Obama’s arms—were carefully blacked out.

Hamid collected other trinkets. He took a small rectangle of elastic fabric and asked one of his friends in the prison to draw a Canadian flag on it in red ink. He hung this from his bunk with a tiny thread to remind him of home.

HAMID got his first real reason to believe he might see home again earlier this year. A representative from the prosecutor’s office told Hamid he had reviewed his file and judged him to be innocent. He told Hamid he had requested a retrial. An Iranian intelligence director and expert on the People’s Mujahedeen then questioned Hamid.

“He told me right from the beginning, ‘If I find out you have any involvement, I’m going to push for the execution. If not, I’m going to help you get out,’ ” Hamid says.

Six weeks later, the intelligence director returned to Evin Prison and said he had investigated Hamid and his family “inside and outside” Iran and found no evidence of involvement with the People’s Mujahedeen. A retrial was set for August. Iranian prosecutors could not officially confess their mistakes. Instead, they accused Hamid of yet another crime: “gathering or colluding against the domestic or international security of the nation.”

Retrials should not include new charges, and this judicial miscarriage is one of many Hamid suffered. But the charge also carries a maximum sentence of five years, time Hamid had already served. He was found guilty, sentenced to five years and ordered released.

The judgment might have been politically motivated. It came just as Iran’s new president, Hassan Rouhani, made a trip to the United Nations in New York on a mission to mend Iran’s relationship with the West.

Freedom, when it finally came, was muted relief.

Hamid had a chance to say goodbye to his friends in the prison. They were happy for him. He gathered some souvenirs: a diary, a couple of the thread dolls, his elastic-band flag. Then, at around nine o’clock in the morning, he walked out the prison door.

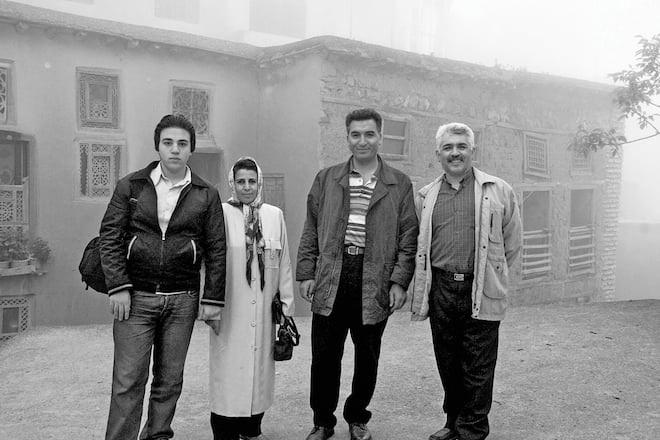

“I heard screaming from 20 or 30 guys. They were my friends, they had finished their sentences, they were outside. My sister, my nephews—they are running toward me, and the guard is trying to keep them away from that area, in front of the jail wall. Everybody is happy. My sister, she’s crying. It was an emotional moment. It was very emotional for my sister,” he says.

“For me, I didn’t care that much. All I wanted was exoneration from the justice system. They knew I was innocent right from the beginning. They made a mistake. I didn’t want any money from them. All I wanted was an apology to my family, to my brother. And when I didn’t get that, to me, it didn’t matter that I was outside the door, back in the outside world.”

Hamid called Antonella right away. Her happiness was numbed by worry that Hamid’s freedom was temporary and would somehow be reversed. She says she could detect fear in Hamid, too.

“I could hear in his voice that he was not free. I could hear that they still held something of him, and I was concerned,” she says. Hamid did not sleep during the five-hour flight to Rome. A diplomat from the Canadian embassy met him at the airport to keep him company until the second leg of his journey to Toronto. He didn’t sleep during that flight, either. “When we reached Canadian airspace in Newfoundland, I know I’m back home,” he says.

A Canada Border Services Agency official allowed Antonella past the first security gate so she could see Hamid first. They had a short time alone, then the two walked arm-in-arm through the sliding glass doors to where a crowd was waiting for Hamid.

“It was overwhelming,” Hamid says. He didn’t expect so many people, especially strangers. Among the crowd was Salman Sima, who was jailed with Hamid at Evin. Former Canadian resident Saeed Malekpour is still there.

TODAY, Hamid and Antonella sit beside each other and clasp hands. Antonella reaches her second hand over and rubs it on top of his. They call each other “chica” and “chico.” They want people to know how grateful they are—to Amnesty International, the Canadian government, friends and strangers.

“You know, the past four and a half years that I was in the general population, every morning around 7:30 or eight, we have to get up and sit on the floor of the room to be counted. In the evening, it is the same,” Hamid says.

“It feels weird. All of a sudden, you are in your own home. And the door, you can open it and go for a walk. Space is not limited anymore.”

Are you sleeping now? Hamid is asked.

Yes, he says.

No, says Antonella. “Not really. He’s not sleeping. He sleeps a few hours. He doesn’t sleep a full night. I see things that other people don’t see. I just see that that he has suffered a lot. I see it in his eyes, in his face.”

Their home and the cemetery behind their backyard are in a tiny valley that traps heat and has kept surrounding tree leaves mostly green, even late in October. A pot of heather blooms in soft purple on a back-deck table.

“We’re trying to get our life back together,” Hamid says. “It’s a long process. It’s been five years and four months I’ve been away from my life. And so far, we’re fine. We’ve managed to catch up with a lot of things, and I’m hoping in the near future we’ll finish it off completely and move on with our life.”