How 2016 became the year of the ‘nasty woman’

In a hard 2016, a misogynistic insult from Donald Trump became a rallying cry

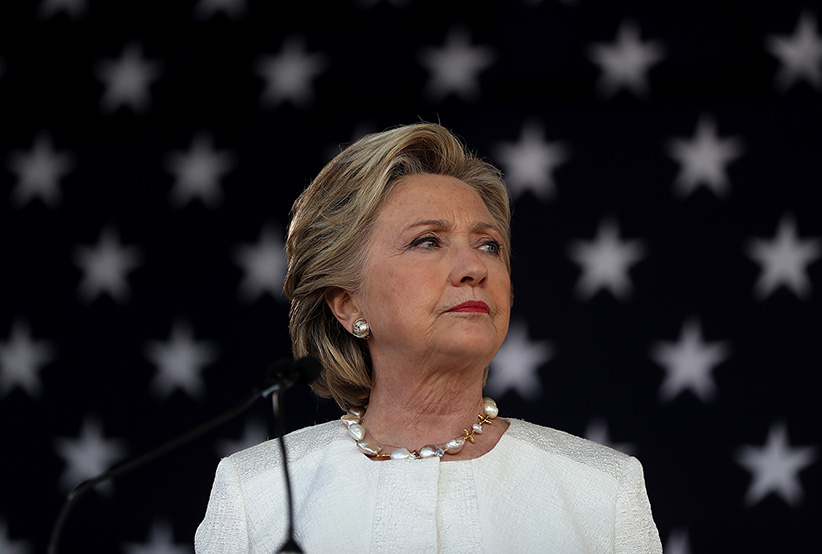

Democratic presidential nominee former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton speaks during a campaign rally at Pasco-Hernando State College East Campus on November 1, 2016 in Dade City, Florida. With one week to go until election day, Hillary Clinton is campaigning in Florida. (Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

Share

Our annual Newsmakers issue highlights the year’s highlights, lowlights, major moments and most important people. Read our Newsmakers 2016 stories here and read on for Anne Kingston’s insights on the year for feminism and activism in the face of it all.

During the last presidential debate, as Hillary Clinton was describing her plan to put more money into the Social Security Trust Fund, she took a jab at her opponent: “My Social Security payroll contribution will go up, as will Donald’s, assuming he can’t figure out how to get out of it.” As she continued speaking, Trump tried to cut her off: “Such a nasty woman,” he muttered.

If Trump’s aim was to make Clinton—or women generally—cower, he failed miserably. His rude interruption became a rallying cry, a defiant capper for a year that saw “nasty women” front and centre, though never without a price being paid.

Trump’s attempted insult was plastered on T-shirts, some sold to benefit Planned Parenthood, which he threatened to defund. One provided a useful definition: “Nasty women. noun. 1. a confident, independent female who gets s–t done.” Within hours, “Binders Full of Nasty Women,” a private Facebook page, popped up to let women vent and mobilize without fear of harassment.

“Nasty women” are used to that. Witness the abuse directed toward the year’s first “nasty woman,” Andrea Constand, the Toronto native who made headlines in January after the 2006 civil suit she filed against Bill Cosby finally led to sexual assault charges being filed against the once-beloved comedian. No one listened when Constand came forward in 2005 with then-shocking allegations that the beloved entertainer sexually violated her. She wasn’t the first but was the most determined. It took a chorus of more than 50 women to see Cosby finally face criminal charges, in a case that is ongoing. Constand told the Toronto Sun last summer that she refused to let the experience “define me.”

MORE: Can America’s activism go beyond safety pins?

Months later, the Jian Ghomeshi criminal case introduced a new cast of “nasty women,” three plaintiffs who bravely came forward but proved poor witnesses after it was discovered they misrepresented communicating with or seeing Ghomeshi after the alleged assaults. Then there was the archetypal “nasty woman,” criminal lawyer Marie Henein, whose masterful defence of her client, found not guilty on six counts, didn’t preclude her from being heaped with criticism for doing a job that by definition entailed berating other women. Ghomeshi also issued an apology to the fourth plaintiff, Kathryn Borel, whose eloquent, defiant statement on the courtroom steps elevated her to the year’s ultimate “nasty woman.” The Ghomeshi case will not be over “until he admits to everything that he’s done,” she said. It was Borel, not Ghomeshi, who dominated the next day’s news.

“Nasty women” had a teeter-totter time of it in entertainment. The all-female Ghostbusters’ remake became a cultural flashpoint, with some men registering anger that girls had hijacked their adolescent memories. Reviews were positive; box office was middling to good enough to drive chatter of a sequel. Filming also began on an all-star, all-female remake of boy’s caper Ocean’s Eleven. Notorious “nasty woman” Samantha Bee also asserted her place in the boys’ club of late-night comedy with on-point satire and outrage. But we also saw steely Resistance fighter Rey, the lead character in Star Wars: The Force Awakens, excluded from the film’s merchandise, igniting a #WheresRey protest.

It was that kind of year, one in which women said they weren’t going to take it any more. Former Fox News anchor Gretchen Carlson sued Fox CEO Roger Ailes for sexual harassment, winning a stunning $20 million, and igniting a flurry of similar complaints that saw the lecherous boss turfed from the network, albeit with a $40-million exit package. After Trump boasted of sexually assaulting women on video, Canadian Kelly Oxford, a Twitter powerhouse, asked women to share their first experience of sexual assault. She got 50 responses a minute—27 million in three days.

Yet more than a dozen women coming forth to say Trump assaulted them failed to curtail his bid for the U.S. presidency. It was left to “nasty woman” Kate McKinnon, Hillary Clinton’s Saturday Night Live doppelgänger (and Ghostbusters star) to sing a hauntingly elegiac version of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” ending with another rallying cry: “I’m not giving up and neither should you.” An even more radical message was delivered in a Roseanne Barr quote retweeted by Andrea Constand earlier: “The thing women have yet to learn is nobody gives you power. You just take it.”

[widgets_on_pages id=”Newsmakers 2016″]