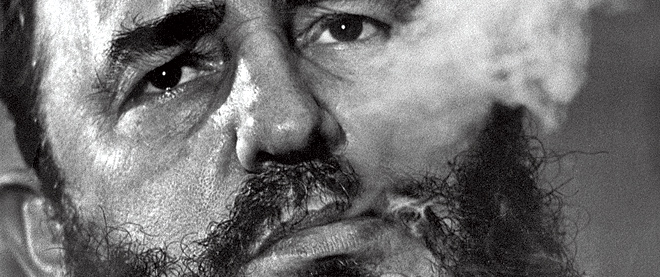

Isn’t Fidel great?

A lavish miniseries on Castro tries to polish the regime’s legacy

Share

On Oct. 16, 1953, while on trial for leading the attack on the Moncada Barracks—which laid the groundwork for the Cuban Revolution—a young Fidel Castro famously told the court, “Condemn me. It doesn’t matter. History will absolve me.” Apparently, the Cuban government can’t wait that long. Amid continuing reports of the now-retired leader’s frailty, the regime has bankrolled a documentary that seeks to portray Castro as just short of divine. He Who Must Live, a miniseries that began airing on Cuban TV last month, remembers the 83-year-old, who served as Comandante en Jefe for nearly 50 years, as a man who did so under constant threat, surviving an alleged 638 assassination attempts, largely perpetrated by the U.S. Says Ann Louise Bardach, an American journalist and author of the 2009 book Without Fidel: A Death Foretold in Miami, Havana and Washington, “This is the kind of pre-emptive eulogy for the Maximum Leader.”

On Oct. 16, 1953, while on trial for leading the attack on the Moncada Barracks—which laid the groundwork for the Cuban Revolution—a young Fidel Castro famously told the court, “Condemn me. It doesn’t matter. History will absolve me.” Apparently, the Cuban government can’t wait that long. Amid continuing reports of the now-retired leader’s frailty, the regime has bankrolled a documentary that seeks to portray Castro as just short of divine. He Who Must Live, a miniseries that began airing on Cuban TV last month, remembers the 83-year-old, who served as Comandante en Jefe for nearly 50 years, as a man who did so under constant threat, surviving an alleged 638 assassination attempts, largely perpetrated by the U.S. Says Ann Louise Bardach, an American journalist and author of the 2009 book Without Fidel: A Death Foretold in Miami, Havana and Washington, “This is the kind of pre-emptive eulogy for the Maximum Leader.”

A joint undertaking of the Interior Ministry, Institute of Police Sciences and state-approved filmmakers, He Who Must Live is the culmination of millions of dollars, some 240 actors, 800 extras and reams of archival footage. The eight one-hour-long episodes took three years to complete. “There’s no question this is the biggest television blockbuster they’ve ever done,” says Bardach. It’s a tribute, says Dalhousie University professor and Cuba expert John Kirk, that’s fitting of a man who is “seen as the Nelson Mandela of Cuba, but multiplied by a factor of three or four.” To others, however, it’s a calculated attempt to spin Fidelismo at a time when the government, now headed by Castro’s younger brother Raúl, is becoming increasingly unpopular. In a country where free speech is limited, says Ismael Sambra, a former Cuban journalist who spent five years in jail before being exiled to Canada in 1997, the government “knows how to manage the media to inspire compassion?.?.?.?to justify their position against the enemy and the opposition.”

In filming the series, director Rafael Ruiz Benítez says he used a variety of genres to “give the viewer more information about the facts.” One problem, however, is that the central “fact”—that Castro survived a staggering 638 attempts on his life—is being dismissed by many as fallacy. To be sure, there have been more than a few efforts to off the Comandante. In 1975, a U.S. Senate committee report found “concrete evidence” of at least eight CIA-led plots, which include Mafia figures, Cuban dissidents, and everything from high-powered rifles to poison pens. As recently as 2000, Luis Posada Carriles, a Cuban-born ex-CIA operative, was arrested in Panama City with 200 lb. of explosives, apparently planning to kill Castro while he delivered a speech. Cuba expert Robert Wright, who teaches history at Trent University, says Cuban ministries are completely closed to researchers, making it “well nigh impossible to get Cuban documents”—or verify the film’s bold claim. (It’s also made in the 2006 British documentary 638 Ways To Kill Castro.) But according to Bardach, who has done extensive research on the subject, the true figure is likely in the “double digits, not triple digits.”

As Kirk sees it, the actual number of assassination attempts is irrelevant. He says that rather than getting lost in whether it was 638 or 529, the point is “that there have been dozens proven beyond a shadow of a doubt.” But to others, the figure, and the reason they say it is being deliberately overblown, cuts to the very core of the country’s political problems. According to Ana Faya, a consultant for the Ottawa-based FOCAL (Canadian Foundation for the Americas), by portraying Castro—and Cuba—as the perennial victim of aggressive U.S. imperialism, the government can blame the country’s problems on the conflict, rather than the regime’s domestic policy. “It’s a propaganda that has been going on for 50 years,” says Faya, who served as an official in Cuba’s Communist party for more than a decade before coming to Canada in 2000.

In fact, says Faya, the main conflict is “between the Cuban government and its population”—and it’s getting worse. Amidst an economic crisis and an increase in reported human rights abuses, the dissident movement appears to be gaining traction. The death of Orlando Zapata Tamayo, a Cuban political prisoner who perished in February after an 83-day hunger strike, prompted international outrage and an unprecedented statement from Raúl Castro. (He said he lamented the death, which he blamed on Washington.) Other jailed dissidents have since taken up their own hunger strikes; their wives and mothers, called “Ladies in White,” have protested in Havana. Says Bardach of the Cuban government, “They have a big problem, and it’s not just U.S. opinion.”

All of which explains why He Who Must Live is much more than a retrospective on the life of a long-serving leader. But considering the significance of Castro’s legacy in the ongoing narrative of La Revolución, this should come as no surprise. On April 17, 1954, while imprisoned for the raid on Moncada, he wrote a letter to a comrade, reminding her: “We cannot for a minute abandon propaganda, for it is the soul of every struggle.” Clearly, the struggle rages on.