Miami vice: How a diplomat’s kids ended up in a fatal drug heist

The story of a diplomat’s two sons—one killed, one jailed—is the story of Miami’s youth. Inside what really happened in Miami.

Share

On the last Monday in March, Jean and Marc Wabafiyebazu took their mother’s black BMW 3-series sedan for a ride around Miami. It was a hot afternoon—28 degrees—and the sun blazed through canopies of palm and banyan trees above streets lined with pink and red tropical flowers. It was a world apart from the bleak, snow-covered Ottawa hometown they left behind less than two months ago.

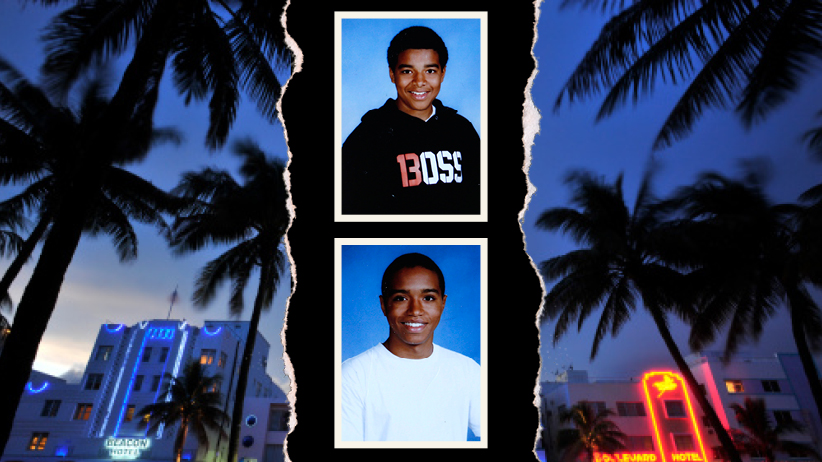

Jean, 17, and Marc, 15, had moved to Miami to join their mother, Roxanne Dubé, a longtime Canadian diplomat, and former ambassador to Zimbabwe, who has been Canada’s consul general to Miami since last November. It was, said their father, Germano Wabafiyebazu, a dream destination.

They drove past the security guard that day and out of their gated community in Pinecrest—where they lived with their mother in a primrose ranch-style home—and deeper into the rundown parts of the city’s Coral Way neighbourhood, about 30 minutes away. They reportedly had their mother’s permission to take the car. On the outside it was adorned with consular licence plates—and inside, two loaded guns.

They pulled up to 21-year-old Johan Ruiz’s ground-floor apartment at an aging yellow low rise at 3600 17th SW Terrace. Ruiz was a friend of Joshua Wright, whom Jean had met two days earlier at Ultra, an electronic dance music festival in Miami. This part of Coral Way is the kind of neighbourhood where everyone keeps their curtains closed. Across the street sat a rusty green and red hatchback with a smashed windshield, and an old bulldog behind a metal fence.

The boys, evidently, had decided to cut class on this day. Growing up in Ottawa, they were inseparable and attended Lycée Claudel, a French private school in Ottawa. But in Miami, they attended different schools. Jean was enrolled in Grade 12 at Gulliver Preparatory School, one of Florida’s most prestigious private schools, with tuition starting at US$31,000. Notable alumni include George P. Bush, George W.’s nephew, and singer Enrique Iglesias. Outside after school, surrounded by perfectly manicured grounds and a mural by Romero Britto, students in khaki pants and polo shirts study and wait to be picked up by parents in Range Rovers and Mercedes.

A few blocks away, Marc attended Grade 9 at Palmetto Senior High School, a public school sometimes referred to by its nickname, “Palm-Ghetto.” It was recently the subject of a photo essay on the Miami New Times website that showed filthy conditions inside, including cockroaches and condoms on the floor and holes in the walls.

About the only thing the two schools have in common is a reputation for underage drinking and drug use among students. And they seemed to have provided fertile ground for the brothers as they explored their new life in the fun-filled city of Miami.

Even before he moved south, Jean’s Twitter feed was peppered with retweets from accounts such as “Weed Tweets” and “Really Stoned Panda,” including phrases like “Stop worrying about dumb s–t and get stoned” and “A couple that blazes together, stays together.” In one tweet, Jean writes, “startin off the day wit mah blunt o herb.” His profile photo is of him holding bottles of hard liquor. From January until it was removed this week, Marc had a photo up on Facebook showing him smoking what appears to be marijuana. Neither Jean nor Marc have been in trouble with the law before.

In front of Ruiz’s apartment in Coral Way, Marc waited in the car. Jean’s plan, according to police: to rob two pounds of marijuana worth roughly $5,000 from Anthony Rodriguez, a suspected drug dealer waiting with Ruiz and his friend Joshua Wright.

According to Rodriguez’s arrest record, he had received a text message from Wright asking him to bring the marijuana. A few minutes went by. Then Marc heard a flurry of gunshots and bolted from the car and through the door of the decrepit one-bedroom apartment. Inside, Wright was already dead on the floor with multiple gunshot wounds. Jean was nearby suffering from at least one gunshot wound. Marc allegedly picked up one of Jean’s guns and fired it as he chased Rodriguez down the street and into his car, according to the Miami Herald in a recent story citing police sources.

A nearby squad car showed up and an officer arrested Marc and took him to the Miami-Dade juvenile detention centre, charged with felony murder and threatening to kill a police officer while being interviewed back at the police station. (Under Florida law, anyone associated with a crime in which someone is killed can be charged with murder.) His brother was taken to the hospital, where he quickly succumbed to his injuries. Ruiz was taken to the hospital for gunshot wounds to the stomach, and wasn’t arrested or charged. Rodriguez, who was shot in the arm, was arrested at a nearby gas station and charged with two counts of felony murder and one count of possessing marijuana with intent to sell, according to his arrest report.

Police have not said how Jean got the firearms, but Miami locals and students say it’s extremely easy, and common, for young people to steal guns from family members or buy them cheaply in certain parts of town.

With a funeral to plan for one son, whose body has been sent back to Ottawa, and the other held in a youth detention centre notorious for abuse and rape behind its walls, Dubé is living out a parent’s worst nightmare, no doubt racking her brain trying to make sense of it all. How, in six short weeks, did things go so tragically wrong?

Outside of the apartment a few days later, after the crime scene had been cleaned of blood and with Ruiz still in the hospital, melted tea lights, empty 32-oz. bottles of Olde English malt liquor and cognac-flavoured cigarette papers litter the ground, remnants of an impromptu vigil held for Joshua Wright—whose nickname was “Obama”—the night before. A handwritten letter to Joshua from a girl named Emily rests against the building. “I wish I was there I would’ve taken those bullets for all you guys. I can’t stop crying. They will get what they deserve I promise,” it reads. The inside of Ruiz’s apartment is covered in dirt, cigarette butts, empty bottles of alcohol, Crunch candy bar wrappers and broken lamp shades.

Neighbours, including Maria Romero, a woman in her 70s, have almost recovered from the chaos. Romero says she heard gun shots just after one o’clock in the afternoon, as she was unloading groceries from her car. “I thought I was going to die. I called the police, but a car was already pulling up,” she remembers. “I never even knew who lived in that apartment. I’m going to try to forget about it.”

Jean and Marc’s classmates were also putting news of the tragedy behind them. On Good Friday, students from Gulliver and Palmetto joined hundreds of other Miami high school students on the strip of beach at Ocean Drive and 7th Street to celebrate the long weekend. Teens from 14 to 19 years old were competing to see how much rum they could funnel down their throats, and guys pawed at girls channelling Miley Cyrus’s dance moves. The haze of pot smoke grew thicker with each passing hour. The Miami police watchtower was just a few feet away overseeing it all.

None of the kids seemed to care; they do this almost every weekend. If March 30 had not happened, Jean and Marc likely would have been here too. One girl, a Gulliver sophomore who would provide only her first name, Isabel, says the first day Jean came to Gulliver at the end of February, he went around asking every student if they knew where to get cocaine. “Gulliver has a drug problem, so he shouldn’t have had any problems with that,” she says. Isabel didn’t spend time with Jean outside of school, but says he was known among students as a good guy. “He obviously had drug problems, but this is Miami, what can you do?” she says.

Even though the boys were thrilled about the move, their father, Germano Wabafiyebazu, who separated from Dubé a few years ago, was hesitant about a city like Miami. “I wasn’t happy for her to take the children,” he told Global News from his home in Ottawa last Wednesday. He stayed in Ottawa after the shooting but attempted to have daily contact with Marc and Dubé. “I know about Jean . . . what type of friends he had here.” He suspected Jean had been smoking marijuana or taking other drugs. “Knowing him just by looking what he was like, what he liked to wear . . . you could see he was high.” Wabafiyebazu contrasted this with his son Marc, who he described as “perfect” and was just in the wrong place at the wrong time when Jean was killed. If this was the case, Palmetto was not the best place for him.

Students who go to Palmetto describe it as a haven for drugs. Two students say it’s difficult to find someone who doesn’t do drugs. According to several students, one of the popular places to smoke weed during the week is on school property among the row of trees down the middle of campus that students call “the forest.” Kim, a student in Grade 11, says she sits next to a boy in class who regularly chops up pills and snorts them right off his desk. “But weed is the most popular. And there are lots of dealers here,” she says. Katherine, also in Kim’s year, says many students, including herself, go to class high. “Everybody here is connected this way,” she says outside the school after class one day last week. It’s not uncommon to see kids smoking cigarettes and joints in the bathroom, she says. “All of this is kept on the down-low, though. But at this school, no one cares anyway.”

Katherine describes the two main drug dealers at Palmetto: two guys in grades 11 and 12 who carry Tasers in their pockets. “We always hear about kids getting shot, arrested for drugs. They all get competitive, get in fights and have enemies,” she says. Katherine and Kim say they had seen Marc in the hallways at school, but didn’t know him personally.

José, a Grade 9 student who says he is in Marc’s homeroom, says Marc would wear a black belt with green marijuana leaves on it almost every day to class. Very few people who knew Marc at Palmetto would speak about him openly, especially when questions came up about any possible involvement with drugs. One Grade 11 student said he knew Marc from house parties and referred to him as a “pothead.” A few other students said the same thing, calling him “pothead Marc.” Those who had classes with him recall him as being friendly, but shy. They also say that for at least a week before the incident, Marc had been absent from class. Emily, a Grade 9 student who says she was in Marc’s second-period English class, says their teacher started asking students every day during roll call if they had seen or heard from him. “None of us had any idea where he was,” says Emily. “He was always really polite, but we never saw him outside the classroom.”

Marc and Jean’s parents met in 1983. Dubé was a rising star in Ottawa circles. A Fulbright Scholar with a master’s degree in political science from the University of Ottawa, she worked from 1988 to 1996 for former cabinet minister Lloyd Axworthy, who praised her as an ambitious and dedicated part of his team.

From 2005 to 2008, she served as Canada’s ambassador to Zimbabwe. Jean and Marc travelled with her for the posting in Africa. Life in the foreign service is not as glamorous as the public thinks, and hasn’t been for decades. Posting after posting can wear families down, and it’s hardest on the children. Each new city means a new school, a new neighbourhood and finding new friends while struggling with a new culture or language. Stories of kids who fall apart under this immense pressure are sadly common. One Canadian diplomat who has been on numerous postings abroad with children, and who knows Dubé professionally, told Maclean’s it can be tough being a parent under such circumstances. “Every parent who accepts a posting wonders what the impact will be on his child,” the diplomat said. “In some cases, parents might dare hope that a change of surroundings and new friends will shake some bad habits—but the stress, particularly on adolescents, is real and, for those of us parents, frightening.”

Dubé declined an interview request from Maclean’s, asking for privacy as she grieves. “We just want . . . to say goodbye, ever so tenderly and quietly to Jean, our love,” Dubé said in a statement released through the Department of Foreign Affairs. Germano, the boys’ father, is no longer speaking publicly about the situation, having received legal advice to stop.

Marc’s fate now lies in the hands of the Florida justice system and the Canadian government. As consul general, Dubé enjoys certain perks of the trade, though not nearly those of an ambassador. Ambassadors and their families “have full immunity from the criminal jurisdiction of the host state, and cannot be arrested, tried or convicted under any circumstances,” says a Canadian foreign affairs official. Consular officials only have limited criminal immunity—which doesn’t extend to family members, adds the same official.

The Canadian government could intervene in rare circumstances, such as if Florida prosecutors sought the death penalty. But under Florida law, that punishment is not an option for anyone under 18. Even in criminal proceedings when a capital crime is involved, Canada has been loath to intervene in American criminal proceedings, says another foreign affairs official. On the morning of April 8, Marc appeared in court for the second time, where it was announced a grand jury will consider whether he will be formally charged with felony murder. The judge set a hearing for April 20 to hear the jury’s decision.

If tried as an adult and convicted of felony murder, he could face a life sentence without parole. If convicted as a youth, he would be eligible for parole after 15 years. Felony murder convictions, where the offender didn’t kill someone, but was involved in a crime where someone was killed, are relatively common in the United States—and controversial. Human rights groups are campaigning to have such laws abolished, arguing they are unconstitutional. (The Supreme Court of Canada abolished felony murder in 1990.)

This week, a Facebook page to remember Jean was created. It has more than 500 “likes” with comments from people from Harare to Vancouver. “Those who knew you, knew how amazing you were . . . Who would have imagined that you would die at 17?” wrote Nave Lyrah. “Who would have thought that you would end up in drugs? . . . We just wish you never even moved to Florida.” Daoji Yang, a Gulliver student, posted a comment about how Jean wanted to be a businessman after graduation. “I just want you to know [I] will always remember you as a nice, humble gentleman and a great friend of mine,” Yang wrote.

A few days after Jean was killed, someone from Ontario using the Twitter handle @DaaPrinceHakeem tweeted a link to a news report about the incident with the message: “RIP Jean I told u to stay away from the drug life.”

Back in Coral Way, Jeff Stone, the landlord of the apartment building where Jean was shot, arrives with his son, who looks about six years old, to clean out the unit. After a year and a half as his tenant, Ruiz will no longer be living there, Stone says. “I’m going to repaint and detoxify the apartment now,” he says, hurling bits of broken wall and other debris onto the driveway outside. “It’s time to get back to normal.”

—with Martin Patriquin and Julie Smyth

(Correction: A previous version of this story had reported that at Palmetto High School in Miami, Fla., a star football player was killed after he was run over by a local drug dealer’s car because of a botched marijuana sale. That incident occurred at Palmetto High School in Palmetto, Fla.)