Barack Obama: Four more years

The president begins his second term with political capital to spend, but plenty of barriers in his way

President Barack Obama speaks at his ceremonial swearing-in at the U.S. Capitol during the 57th Presidential Inauguration in Washington, Monday, Jan. 21, 2013. (AP Photo/Pablo Martinez Monsivais)

Share

There will be two Bibles (Abraham Lincoln’s and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s), dozens of balls, thousands of musicians and marchers on parade, and more than a half million people expected to descend on Washington to watch Barack Obama take the oath of office for his second term on Jan. 21. The President will arrive at his inauguration more popular than at any time since his first year in office—with an approval rating of 53 per cent—and determined to push a new agenda through a Republican-controlled House of Representatives whose popularity is a fraction of the President’s.

In his high-minded inaugural address in 2009, Obama declared, “What the cynics fail to understand is that the ground has shifted beneath them, that the stale political arguments that have consumed us for so long no longer apply.” Unfortunately, the last four years proved the cynics right. If anything, partisanship has grown more intense, and Congress more averse to compromise. In the House of Representatives, Speaker John Boehner cannot control a significant number of conservative hard-liners in his own caucus.

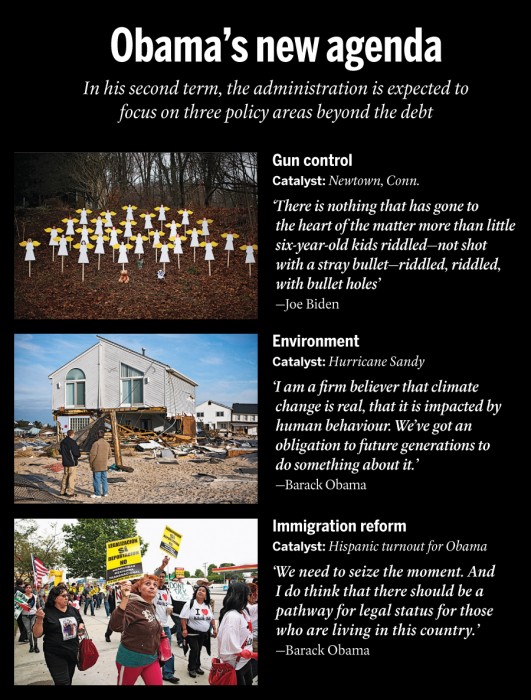

Obama comes to his second term reinvigorated and combative with a policy agenda that looks hastily ripped from recent headlines: a post-Newtown attempt at gun control, a post-hurricane Sandy renewed interest in climate change, and a return to the issue of comprehensive immigration reform in the wake of an election in which he won 71 per cent of the Latino vote. But while he embarked upon his first term in the midst of an economic crisis, his second term unfolds amid a made-in-Washington fiscal crisis and partisan stalemate.

Crucial fiscal negotiations are coming up in the weeks ahead that could lead to the U.S. defaulting on its debt, or to a shutdown of the federal government. Obama claims an election mandate to reduce the deficit through a combination of spending cuts and tax increases. But that doesn’t seem to matter to many House Republicans, who demand massive spending cuts to social welfare programs as the price for raising the debt ceiling; they say they will block any new tax increases.

At least 50 or more Republicans are “immune to wider political trends, broader American public opinion, or for that matter the overall results of an election,” observes Norman Ornstein, a congressional analyst at the American Enterprise Institute, a think thank in Washington. Their districts are safe Republican seats and their biggest personal concern is the prospect of losing to even more conservative Tea Party-backed challengers in a primary campaign. They are more worried about staying pure in the eyes of anti-tax and anti-deficit groups and disinclined to approve any compromises with Obama reached by more pragmatic Republican leaders in the House.

“The big problem is the leaders are not in a position to persuade a significant share of their own members,” says Ornstein. The result is that Obama finds himself negotiating with a Speaker who increasingly doesn’t speak for his own caucus, and whose own survival as leader of House Republicans is shaky.

With that partisan battle as a backdrop, Obama’s suddenly ambitious second-term agenda hits two more hot button issues for Republicans: immigration and gun control. In his victory speech, Obama spoke of “fixing our immigration system.” His supporters have made it clear they expect action on comprehensive immigration reform, including a pathway to citizenship for the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S., something Obama had promised and failed to deliver in his first term. Leaders of several large Latino and Hispanic advocacy groups in the U.S. have pledged that lawmakers will be rated on their supportive votes on reform. “With these report cards, Latinos will be able to determine who deserves their support in the 2014 election cycle,” said the groups, which included the National Council of La Raza and Voto Latino, among others.

Some Republicans are beginning to sound more open to legislation too, as a way to make up lost ground with the fast-growing segment of the electorate. Sen. Marco Rubio, a Florida Republican of Cuban descent, is designing an immigration reform proposal that has the support of former vice-presidential candidate Paul Ryan. However, many Republicans remain opposed to any kind of “amnesty” for “illegal immigrants.”

Meanwhile, the Obama administration is already at work on a gun-control agenda in response to the elementary school shooting in Newtown, Conn. Vice President Joe Biden is leading a task force reviewing policy options, including reinstating an assault-weapons ban, universal background checks, limits on high-capacity magazines, and improved restrictions that are supposed to keep the mentally ill from having firearms. “In all my years involved in the issues, there is nothing that has pricked the consciousness of the American people, there is nothing that has gone to the heart of the matter more than the image people have of little six-year-old kids riddled—not shot, but riddled, riddled—with bullet holes in their classroom,” Biden said after meeting with several stakeholders.

Obama said he will try to enact as many of Biden’s recommendations as he can, whether through Congress or unilateral presidential orders. But most of the recommendations would require the assent of the House, making their passage questionable. “My starting point is not to worry about the politics. My starting point is to focus on what makes sense, what works, what should we be doing to make sure our children are safe,” Obama insisted Monday. All the while, gun shops reported soaring sales as enthusiasts feared Obama would take their weapons.

Obama said he will try to enact as many of Biden’s recommendations as he can, whether through Congress or unilateral presidential orders. But most of the recommendations would require the assent of the House, making their passage questionable. “My starting point is not to worry about the politics. My starting point is to focus on what makes sense, what works, what should we be doing to make sure our children are safe,” Obama insisted Monday. All the while, gun shops reported soaring sales as enthusiasts feared Obama would take their weapons.

A third element of his second-term agenda is climate change, which moved up the priority list after hurricane Sandy’s devastation on the East Coast, and the endorsement of New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who touted Obama as the most likely candidate to act on the issue.

There is little chance that a carbon tax or climate-change bill could make it through the Republican-controlled House, but Obama has other options. In his election victory speech, he talked about the “destructive power of a warming planet,” and pledged to work on new steps on climate change, which could include further carbon regulations for large emitters, such as power plants.

Of particular interest to Canada is the selection of Massachusetts Sen. John Kerry as his nominee for Secretary of State, replacing Hillary Clinton. Kerry has been a long-time advocate for climate issues and is expected to take a more aggressive stance in international climate negotiations. In addition, environmental groups are hoping he will be more sympathetic to their concerns about TransCanada Pipelines’ proposed Keystone XL pipeline, that would bring diluted bitumen from Alberta’s oil sands down to refineries on the Gulf Coast of Texas. The pipeline is undergoing a review by the State Department, with a final recommendation for a presidential permit to be made by the next Secretary of State.

“Sen. Kerry has a strong record on climate and will naturally be concerned about his legacy at the State Department going forward. He will likely take a closer look at the decision around the Keystone XL because the decision will be on his watch,” said Danielle Droitsch, a director of the Canada Project for the National Resources Defense Council in Washington. Groups like hers will ask Kerry to challenge a State Department position that the pipeline would not increase global carbon emissions because the oil sands crude would be developed at the same pace with or without the project. “We will be asking him to take a closer look, because the previous environmental review on climate impacts from the pipeline were very flawed,” she said.

(In another development of significance to relations with Canada, Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano, who has been working closely on border-management issues, is staying put.)

Obama also faces some testy Senate confirmation hearings for new cabinet appointees.

Obama has nominated former Nebraska senator Chuck Hagel as defence secretary, whose hearings are likely to be dominated by criticism that he would be too eager to downsize the military or not be sufficiently supportive of Israel. Hagel, a Republican and Vietnam war veteran who is close to the vice-president, is one of several appointees with close White House ties, upending the “team of rivals” cabinet Obama brought in during his first term. Obama has also nominated his top counterterrorism adviser, John Brennan, to head the CIA. Brennan was instrumental in Obama’s targeted killing program that uses armed drone aircraft to take out suspected terrorists abroad, and could face a contentious confirmation hearing about the drone policy, especially the administration’s claim that it has the power to target U.S. citizens abroad.

In preparation for the fiscal wrangling with Congress, Obama is replacing Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner with his chief of staff, Jack Lew, who is not well known in the financial world but is a veteran of Washington’s budget wars.

He’ll need that experience as Obama seeks to avert the financial disaster that would come with the U.S. defaulting on its bonds. In the recent year-end fiscal-cliff negotiations over taxes, Boehner was unable to persuade his own Republican House members to pass a permanent tax cut for almost all Americans because it also allowed taxes to rise on annual earnings over $400,000. In the end, Boehner was forced to pass it with more Democratic than Republican votes. Whether Boehner would risk such a move again is uncertain. There is only so often he can bring forward legislation opposed by a majority of his caucus. “The more you do this, the more you weaken yourself as Speaker,” says Ornstein.

Yet somehow Obama needs to persuade Republicans to authorize more federal borrowing. Federal government borrowing already hit the current debt ceiling of $16.4 trillion on Dec. 31. The Treasury has since been using emergency accounting authority to pay for government operations. Analysts say the measures can only buy time until mid-February, when a legislated solution will be necessary to prevent the U.S. from defaulting on its debts. Obama insists that Congress raise the debt ceiling without any conditions, such as additional spending cuts. “They will not collect a ransom for not crashing the U.S. economy,” insisted a combative Obama in a press conference on Monday. “We are not a deadbeat nation,” he added, noting that the new borrowing would merely pay for spending that Congress has already okayed. “You don’t say, ‘In order to control my appetites, I’m not going to pay the people who have already provided me services.’ That is not discipline,” Obama said.

Obama has ruled out other proposed solutions to the debt ceiling, such as minting a trillion-dollar coin, or claiming unilateral power to borrow the money. The moves strengthen his negotiating hand. “If he’d kept those in play, Republicans would say, ‘We’ll breach the debt limit and he’ll do something outrageous like mint a platinum coin and we can accuse him of lawless behaviour,’ ” notes Ornstein. Now it is up to Republicans to decide whether they will call his bluff and risk a potentially catastrophic reaction in the financial markets. “It would be a self-inflicted wound on the economy. It would slow out-growth and possibly tip us into recession,” Obama warned Monday.

In addition, the two sides must contend with $1.2 trillion in across-the-board federal spending cuts that are scheduled to take effect in March. Congress and the President have to wrangle over what to cut—with Democrats aiming to spare social spending and Republicans opposing military cuts. Obama wants to replace some of the cuts with tax increases, potentially in the form of closing “loopholes” and eliminating tax deductions. Republicans are opposed to increasing any revenue.

Separately, Obama and Congress will have to deal immediately with legislation authorizing the operational budget of the government, with existing spending authority set to expire on March 27. Some House Republicans have said they are willing to shut down the federal government unless Obama agrees to further deep spending cuts.

As he gets ready to take the oath of office once more, Obama seems less starry-eyed about bipartisan co-operation than he did four years ago. At his end-of-term press conference, he was pressed to address his reputation as an aloof figure who hasn’t been able to find common ground with Congress because he doesn’t like to socialize with its members. “I’m a pretty friendly guy. And I like a good party,” said the President, who blamed the “paralysis in Washington” on “some very stark differences in terms of policy.” He said he invites lawmakers to the White House, but some choose not to come because the “optics” don’t look good to their constituents. But his tone was wistful. As his second term unfolds, his daughters are getting older and want to spend less time with him, the President said. “I’ll probably be calling around, looking for somebody to play cards with me or something,” he added. “Because I’m getting kind of lonely in this big house.”

10 memorable photos from Obama’s first term:

[mlp_gallery id=88]